|

AE 1, AE 2, and J Class Submarines in The Royal Australian Navy

Dedication. This work about the early submarines of the Royal Australian Navy, is dedicated to my late father Jesse Herbert Gregory BEM. He was born at Southend on Sea on the 30th of July 1890, and in WW1, served in France and Belgium over 4 years in the 2nd Dragoon Guards Queen’s Bays, and was one of the Kaiser’s Old Contemptables. Post WW1, in London he joined the Royal Australian Navy on the 25th of March 1919, and took passage to Australia in J2, one of the J Class Submarines donated by Britain to the RAN. He now served continuously in the RAN until the 29th of January 1945. My father now became an officer of the High Court of Australia, serving the Chief Justice, Sir Owen Dixon over many years, and going with him to India when Sir Owen was appointed by the United Nations as their mediator in the dispute over the partition of India into Pakistan and India. Dad served the crown for over 50 years continuously, and was awarded the British Empire Medal for such service. He died in the 1980’s over 90 years of age.

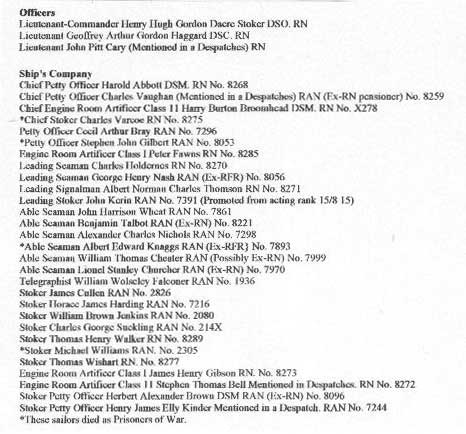

Introduction Since the time of William Bourne, a Dutchman, who, in 1620 was able to demonstrate the potential of submersibles to an audience that included James the 1st, a long line of inventors have strived to conquer the problems of vessels seeking to operate below the ocean's surface. The need to cope with increased pressure was paramount, as the depths at which a Submarine might operate were probed. The French Navy received their first boat in 1889, Holland sold his first submarine to the US Navy in 1900, the price he received, $150,000. At the distance of another 55 years, Holland's Electric Boat Company produced the first nuclear powered Submarine for the United States Navy, at a cost of $30 Million, and that cost did not include the propulsion equipment. A1, Britain's first Submarine was not delivered until 1904, and, across the Channel, in Germany, Krupp, launched his first submersible in 1905, as a consequence, the German government ordered U1. Neither the British Navy nor their German counterpart used any imagination when it came to the possibility of giving an inspirational name to their respective first Submarines. In fact amongst the senior Naval Officers in Britain there was a school of thought that the concept of sneaky Submarines operating secretly below the surface was "Damned unBritish." What ever may have been the prevailing view on the use of Submarines as an arm of Naval Warfare, a Naval phenomenon that would change history when related to the war at sea had been born. The menace of the Submarine had arrived. First Submarines for the Royal Australian Navy At 0600 (6AM) they had passed through the Heads to proceed up the harbour to dock at Garden Island. The long, torturous 18,000 kilometer journey from Portsmouth to Sydney, had been achieved under their engines for 2/3 of the way, and these submarines were towed the rest of this distance. The possibility of war, and its declaration On the 5th came the declaration of war between the two countries, Australia quickly indicated her intentions, and followed the Mother Country, by declaring war on Germany. At the outbreak of war both AE1 and AE2 were refitting at the dockyard on Garden Island. The submarine tender Platypus, had yet to arrive in Australia, meantime HMAS Encounter lent to Australia by Britain until the arrival of the cruiser Brisbane ( still building in UK ) was allocated to act as the Submarine seagoing tender. Major task for RAN ships It was believed operating in the Pacific were the German cruisers Gneisenau and Scharnhorst, the light cruisers Emden, Nurnberg, and Leipzig, and it was thought that Scharnhorst could be off New Guinea. Germany maintained coaling and wireless facilities in the Rabaul area. The Naval Board strategy was to concentrate their naval strength in the Rabaul area. Australia, Sydney, Encounter, with their escorts, Yarra, Warrego and Parramatta, plus the transport Berrima, which had been fitted out as an auxiliary cruiser, and was carrying a 500 man naval contingent together with an army group, were already deployed off Rabaul. To this end, on the 28th. of August AE1, sailed north to Port Moresby, to be followed by her sister boat AE2 on the 2nd of September to join the fleet. Both submarines joined the fleet off Rabaul on the 9th. of September. A landing party from Australia and Yarra, augmented by 100 men from the Berrima Naval contingent destroyed the wireless installations in the Rabaul area, and wrested control of the township of Rabaul from the Germans on the 12th of September. Whilst the fleet was involved here and at Herbertshohe, it was prudent to ensure that the seaward approaches were guarded, and AE2 with an attendant destroyer stood this watch on the 13th of September. Then on the following day with Parramatta, AE1 was assigned this task. AE1 at 0700 ( 7AM. ) sailed from Rabaul harbour in company with Parramatta, having been ordered to patrol east of Cape Gazelle, to watch for any sign of enemy ship action, and then to return to harbour just prior to dusk. Both ships were on station off Cape Gazelle by 0900 ( 9AM. ) when Parramatta steamed southwards proposing to AE1 that she would keep ahead of the submarine, but remain in touch. Parramatta proceeded down the channel between New Britain and New Ireland until 1230 (12.30PM) then reversed course, meantime AE1 steamed North East from Cape Gazelle, and at 1430 (2.30PM), both ships were in visual contact close to the Duke of York Islands. Visibility had now decreased due to hazy conditions, earlier in the day, it had been up to 10 miles, and AE1 now asked Parramatta, " What is the distance of visibility?" and received her response, "About 5 miles." At 1520 (3.20PM) Parramatta had lost visual contact with AE1, and reversed her course to try and regain contact with the submarine. But she was not sighted, and Parramatta reasoning that AE1 had returned to harbour, anchored off Herbertshohe at 1900 (7PM) the sun had set at 1800 (6PM) By now, there were doubts about AE1 and her safety, and, although units of the fleet searched for her, AE1 had just disappeared and was never found. AE1 was the first unit of the Australian Fleet to be lost, and she had mysteriously disappeared without trace. The cause of her loss is unknown, and still remains unsolved in this year 2000. AE2, The Dardanelles I need to backtrack somewhat. The day after her arrival, AE2 went out on her first patrol to the entrance of the Dardanelles, the objective being to contain both Turkish and German naval forces. This chore was shared on alternate days with the other submarines in the flotilla. Further naval forces arrived in preparation for the attack on the Dardanelles forts from seaward, and the submarines were moved back to Port Mudros situated on Lemnos Island. Now the added distance from the Dardanelles forced the submarine blockade to spend four days on patrol, and then four days rest at Mudros. At the start of this campaign, it was purely a naval one. The plan was to destroy these Turkish forts, force the Dardanelles, reach the Sea of Marmora, then threaten Constaninople ( we now call it Istanbul ) so that pressure would be reduced on the Russian forces in the Caucasus. The bombardment by the fleet on the outer Turkish forts started on the 19th of February, but bad weather then delayed this operation and it was not until the 24th of February that this attack could be continued. Although hits were registered, the forts were not being put out of action. On the 5th. of March, the capital ships took on the inner forts, but defensive mine fields kept the bombardment ships too far away from their targets to be effective. Minesweepers endeavouring to clear these obstacles were themselves under great danger from both artillery and the gun emplacements in the forts. These mines now took a heavy toll of the capital ships involved, Irresistible was sunk, Ocean had to be abandoned, and Inflexible was severely damaged. The French Bouvet sank, losing 600 men. These losses quickly put an end to a purely naval penetration of the Dardanelles, and thus the use of troops in military landings was spawned. Stoker was addressing the problem of a submarine getting through the straits, whilst submerged, he would be safe from the forts and Turkish artillery. But, and it was a very large but, mines posed a great danger. There was the limited battery capacity of his boat. Navigational hazards were present. At its narrowest point, it was only 1,400 yards wide, and the current ran at least at 4 knots. Intelligence thought that there were 5 lines of mines, and most of the passage would need to be taken at periscope depth, making detection of the feather caused by the current very possible. This mine information later proved to be correct. Patrol boats to evade were an added danger. It seemed that AE2 would need to transit a distance of about 35 miles submerged until Gallipoli was passed, and the least current that would be encountered would be 1.5 knots. Stoker would have been well within his rights as the Commanding Officer of AE2 to decide that all these impediments added up to too much risk for both his crew and his submarine. Returning from patrol to Mudros on the night of the 10th. of March 1915, AE2 ran aground off Sagandra Point, and, after three hours was finally towed clear. She now proceeded to Malta for repairs. The Board of Inquiry did not place blame on Stoker, the Naval staff had failed to pass on to him navigational detail that was vital to the submarine approaching the port at night. AE2 left Malta for Lemnos on the 18th. of April with Lieutenant Commander Stoker fearing his chances of piloting the first Allied submarine through the Dardanelles could be thwarted by a British boat. On the previous day, E15 had made an attempt but had gone aground, her Captain and six crew members were killed, and the rest of the crew taken prisoner by the Turks. When AE2 arrived at Tenedos on the 23rd. of April, Stoker was informed that the landings on Gallipoli were set for April 25, and Admiral de Robeck told Stoker "If you succeed there is no calculating the result it will cause, and it may well be that you have done more to finish the war than any other act accomplished." Very heady stuff for this young Submariner. The Dardanelles Their first attempt to enter the Strait was unsuccessful, the forward hydroplane coupling broke, meaning that the Submarine could not dive, and they managed to get safely back to Tenedos by 1200 (Noon) and repairs were made to the coupling. AE2 remained anchored until early on April 25th. when she weighed anchor and set off again for the Straits. It was not until 1919 that the official report of the Commanding Officer of AE2 became available, after his release from the Prisoner of War Camp in Turkey. In brief, this is what happened. AE2 lay off the entrance to the Dardanelles until the moon had set, at about 0230 (2.30AM) on April 25th. she entered the Straits at 8 knots. Searchlights were sweeping the area, the weather was both clear and calm, as the Australian submarine proceeded on the surface. At 0430 (4.30AM) gunfire from the northern shore made AE2 dive to 70/80 feet, and continue through the minefield. Wires mooring the mines could be heard rubbing against the submarine's hull. Twice Stoker had a look through his periscope, and on the third time at 0600 (6AM) he saw that they were but 2 miles from the Narrows. He now kept his boat at periscope depth, ie at about 20 feet. Heavy gunfire from both sides of the Narrows made observation difficult. A small vessel was sighted and at a range of 3/400 yards. A bow torpedo was fired, and AE2 taken down to 70 feet to avoid an attacking Turkish destroyer which was heard to pass overhead. The torpedo struck home, stranding the Turkish gunboat Peykiswket. Subsequently after repairs over 3 months, she was back in service. AE2 now grounded, but was successfully refloated, only to ground a second time under a fort. Again through the judicious use of his engines Stoker was able to refloat his command. By observation, approaching Nagara Point, AE2 found herself surrounded by destroyers, gunboats, and other craft, and decided to dive to 70 feet. Stoker now took the submarine submerged at 90 feet by dead reckoning to pass the Point, and after having a quick look through his periscope found he was heading for the Sea of Marmora. He dived to 90 feet and stayed there for half an hour. Then, bringing the boat up to periscope depth he found Turkish ships in close attendance, once again he took AE2 down to 90 feet, and, at 0830 (8.30AM) found himself again aground, they were stuck at 80 feet. Trim was lost, and for 12 hours AE2 remained submerged, at 2100 (9PM) at last she rose to the surface, and was able to start charging her batteries. Soon after surfacing, Stoker was able to signal his success back to the fleet. Soldiers clinging to the hills around Gallipoli learned this news about AE2's exploits from notices stuck to hillside stumps reading: " Australian Submarine AE2 just through the Dardanelles. Advance Australia." At about 0400 (4AM) on April 26th AE2 was on the surface continuing up the Straits, and at dawn a torpedo was fired at the smaller of two warships, but it did not strike the target. The second vessel turned out to be a Turkish battleship, but Stoker was not able to bring another tube to bear, and the Turk managed to escape. At the entrance to the Sea of Marmora from shore to shore across the Strait a great number of fishing boats was strung out, to avoid them AE2 was dived to 70 feet, and passed underneath them, so achieving Stoker's long held ambition of taking his submarine into the Sea of Mamora. Over several days AE2 unsuccessfully attacked a number of targets, and then on April 29th. they sighted E14, who had also made it into the Sea of Marmora. They parted with the intent to rendezvous the next day at 1000 (10AM), and AE2 bottomed for the night in a bay just north of Mamora Island. Daylight on April 30th. found AE2 on the surface carrying out repairs on an exhaust tank valve, she then proceeded to the position to meet up with E14 at 1000 (10AM.) The boat dived to avoid an approaching hostile torpedo boat, there being no sign of E14, and half an hour later whilst at 50 feet, for no accountable reason, AE2's bow inclined upwards and the submarine started to rise. Notwithstaanding emergency actions to right her trim, the boat partly surfaced only 100 yards away from the enemy torpedo boat. By flooding a forward tank the bows slowly submerged, Stoker tried to level the trim at 50 feet, but his submarine kept plunging downwards. When the maximum depth of 100 feet on the depth gauge was reached, she was still rapidly going deeper. The descent was finally checked by going full astern on both engines, and blowing the main ballast tanks, but these actions gave AE2 a strong upwards thrust, and she burst out onto the surface stern first, and well out of the water. AE2 was in absolute danger! The torpedo boat immediately opened fire, scoring hits and holing her in the engine room, with the pressure hull breached the submarine could not dive. Two enemy torpedoes were fired at AE2 but they missed, and the boat was scuttled. On May 25th. 1915, the American Ambassador in Constantinople confirmed the loss of AE2, and that her three officers and twenty nine crew members had been captured. If Stoker in AE2 had not reached the Marmora, it is likely that no other submarines would have tried to so do, as a result of this daring and successful penetration of the Dardanelles, others followed. The submarine operations in this area put an immense dent in the Turkish Navy's war effort, as a result they lost a Battleship, a destroyer, 5 gunboats some 11 transports and 44 steamers. Submarines made communications by water between the European and Asian sides impossible. This feat of AE2 was to have far reaching effects upon the Gallipoli campaign. We must now return to Anzac Cove and to the Queen Elizabeth where the C in C and his staff are located

On the evening of that first Anzac Day, both the Australian General Bridges and the British General Godley were in favour of immediate evacuation, and they so advised General Birdwood, who, in turn recommended this action to the C in C, General Sir Ian Hamilton. It was 2300 (11.PM.) when Hamilton aboard Queen Elizabeth, clad in his pyjamas, and covered by a British Warm (a short overcoat worn by Army Officers) was handed Birdwood's proposal. Quoted from Moorehead's Gallipoli. Wordsworth Editions Limited, Hertfordshire, 1997:

Hamilton was uncertain about making such a momentous decision, WITHDRAW NOW, or STAY PUT. His senior Naval Advisor indicated that it would take several days to get the soldiers back into the ships. Hamilton again turned to Admiral Thursby and asked him his thoughts, and he replied: "I think myself they will stick it out if only you put it to them that they must." It was at this stage that Roger Keyes, a Royal Navy Officer with Hamilton, was given a wireless message from the Captain of AE2, Lieutenant Commander Stoker, indicating he had penetrated the Narrows, and was now in the Sea of Marmora. Keyes read this message out aloud, and, turning to Sir Ian he said, "Tell them this. It is an omen, an Australian Submarine has done the finest feat in Submarine History, and is going to torpedo all the ships bringing reinforcements into Gallipoli." The die was now cast, Hamiliton had made his mind up, he sat down and wrote to Birdwood.

This message turned the tide on the beach, there was a feeling of relief, the troops have to fight it out, and the previous dangers now seemed somewhat diminished. The inspiration was contained in the postscript, when read out to the soldiers on shore, they began at once to Dig, Dig, Dig, for their very lives. It was not long after this that Australian soldiers were called Diggers, a name that has remained with them ever since. The J Class Submarines Initially 8 submarines were planned, but this number was cut back to 6, and two were ordered from three Dockyards, Devonport, Pembroke and Portsmouth. The design surface speed was planned at 20 knots, and to achieve that speed, three diesels, each of 12 cylinders were developed, whilst the submerged speed of 10 knots needed two engines with associated electrical motors. October 15 1918 (not 1917 thanks to Pauline Eismark "Correction Submarine J6 sunk October 15 1918, NOT 1917" ), J6 was sunk, and the Admiralty decided to build J7, so that a Class of 6 boats would be maintained, and she was built at Devonport, completing in 1918. During WW1, J2 achieved the distinction of torpedoing a German surfaced submarine. After the loss of both AE1 and AE2, during WW1, the Australian Naval Board had recommended that two larger submarines be ordered from England, but the Admiralty had responded that the output of all submarines from British Yards was required for Home Waters. There was much talk in Australia about the desire to build and maintain warships locally, and to this end, ten selected personnel from the Cockatoo Commonwealth Naval Dockyard in Sydney spent 18 months in England studying submarine construction. After much back and forth discussion between the Australian Naval Staff, the Australian Government and the Admiralty about the composition of the Royal Australian Navy, and where and what ships would or should be built, no decisions were reached. William Morris Hughes, the Australian Prime Minister of the time, with his Minister for the Navy, Sir Joseph Cook, sailed to England to attend the Imperial War Conference, followed by the Peace Conference, arriving at Liverpool on the 15th. of June 1918. After further discussions with the Admiralty, it was learned that a gift of 6 submarines to Australia from the British Government was very likely to be forthcoming. In January of 1919, this prediction came to pass, and the offer of the gift of the six J Class Submarines, was " gratefully accepted" by Australia. J Class specifications Their surface speed turned out to be 19 knots and when submerged 10 knots. The maximum diving depth, 300 feet, whilst the periscope depth ,was somewhat deeper than that of the AE's, for the J's, it was 28 feet. Initially a 3 inch deck gun was fitted, but all boats had this converted to a 4 inch gun. Torpedo Tubes Depot ship Platypus and 6 gifted Destroyers The oiler Kurumba was also part of this fleet of ships, and crews were now needed to be found for these vessels plus the specialised crews for the 6 J Class Submarines. The Admiralty helped by allowing recruiting to be made amongst British Naval personnel, and 31 Australian sailors had opted for the Submarine Service. Crews for the J's were found, and they were to be manned by Royal Navy Officers, whilst six RAN Sub-Lieutenants were carried to gain watch keeping experience on the passage from UK to Australia. At this stage my Father, Jesse Herbert Gregory, having spent WW1 in the British Army, and survived service in Belgium and France, was discharged from the Army. Just prior to signing of the Armistice, he had married my Mother, Minnie Winifred Greening, on the 24th. of August 1918. Dad now joined the Royal Australian Navy in London, and was drafted to J2, and undertook the passage to Australia in her. My Mother and my maternal widowed grandmother, followed later by merchant ship The Flotilla Commander in Platypus was Commander E C Boyle VC. RN, and his Flag Lieutenant was Lieutenant G D'Oyley Hughes DSC. RN, who had signed on for a two year stint with the RAN. The Naval Board in Australia wished to have their new acquisitions available to take part in the proposed Peace Day celebrations in June of 1919. It was planned that the 6 Submarines plus Sydney, and Platypus would sail from Portsmouth on the 5th. of April, bound for Australia via the Suez Canal and the Torres Strait. Kurumba was to sail several days earlier to be able to fuel the destroyers at Aden. The Australian Naval Board as they were having difficulties in finding crews for the 6 gifted destroyers requested that they be placed in temporary reserve in Britain, and this was achieved. The 6 J boats were commissioned into the RAN on the 25th of March 1919. After several delays, the 6 J Class Submarines finally cleared Portsmouth bound for Sydney on the 9th of April, escorted by Sydney and Platypus. In poor weather, when south of Portsmouth, J5 collided with the French sailing ship, Terreneuvian Yolande, and she subsequently sank. An Admiralty Board of Inquiry blamed the submarine entirely, and expressed "severe displeasure" to Lieutenant J.R.Peirson (Commanding Officer) for "leaving the sailing vessel after the collision without satisfying himself that she was in a safe condition." The RAN also convened an inquiry, and the court found, "that while blame was attributible to the schooner for not carrying lights and not exercising care, Sub Lieutenant J.B.Newman did not exercise proper judgement, in that having sighted a sailing vessel without lights almost ahead, he did not take immediate steps, to avoid her as laid down in Article 20 Regulations for Preventing Collisions at Sea." The Naval Board "found some blame attributable to Sub Lieutenant Newman and expressed their displeasure." This officer after specialising in Signals as a Lieutenant in 1923, transferred to the RAN Shore Wireless Service in 1939, and was promoted to Commander in the Auxiliary Services, to take charge of Shore Wireless Stations and Director of Naval Communications at Navy Office. The Admiralty settled a civil claim brought on by this collision, and, on behalf of the Australian Government paid the owners of Terreneuvian Yolande 4992 Pounds plus interest. The flotilla sailed via Gibraltar, Malta, the Suez Canal to Aden, thence to Colombo and Singapore, they left for the last leg to Australia on the 19th. of June. Sydney was towing J1, as she had engine problems,with Platypus escorting her clutch of the other 5 submarines. On the 20th. of June, Sub Lieutenant Larkins went missing from J2, he had either fallen overboard, or was washed off the casing where he had been asleep. All ships turned back, but his body just disappeared and was never recovered. The flotilla arrived at Thursday Island on the 28th of June, and finally made it into Sydney Harbour on Tuesday the 25th. of July, to be welcomed by His Excellency the Governor General. It had been a long, arduous, and boring voyage. After the J boats arrived they were all in dire need of an extensive refit. They had all left UK with the minimum of an overhaul which had certainly not been able to rehabilitate them from their tough WW1 service. In particular, the submarine batteries were in poor condition and in need of attention. The Dockyard facilities available for the J Class in Australia left a great deal to be desired. Of the 10 people from the Cockatoo Dockyard who had visited UK to become cognisant with submarine repair proceedures, only a small number were still around, it seemed that their expensive 18 month visit was largely a waste of time. Earlier the Naval Board had decided that Garden Island would house the battery charging facilities, and Cockatoo Dockyard would take care of the refitting role, but in December of 1919, the Board changed its mind, and indicated that Garden Island would be responsible for any refitting of the J boats. Although since their arrival in Sydney the submarines had been in Dockyard hands, very little had been achieved, and progress could not be called satisfactory. At year end, only J7, was really in a suitable mechanical condition, she had been built later than her sister boats, and to date had not led such a hard life. As the Navy had acquired Osborne House which faced Corio Bay at Geelong in Victoria, it was selected as the permanent base for the J Class submarines. The year 1920 HMS Renown with His Royal Highness the Prince of Wales was visiting Australia in 1920, and a Fleet Review in Sydney was planned for this Royal Personage. Platypus shepherded J1, J2, J4, and J5 from Geelong on the 25th. of May arriving safely in Sydney on the 3rd of June. Mid July, J2 and J5 returned to Geelong with Platypus, J1 finally escaped from the clutches of the Dockyard, and left Sydney on the 3rd of August, making it back to Geelong on her own, whilst J4 followed early in September. Various exercises against surface ships of the RAN were conducted in both Port Phillip Bay and around into Western Port, and their flotilla commander now promoted to Captain, Royal Navy. The year 1920 was a difficult one financially for the Navy, the lack of fuel forced the Naval Board to reduce the operation of the surface ships Australia, Melbourne, Sydney and Encounter, below their full potential, but the Board took the decision to keep Platypus and her brood of 6 J boats, fully operational. The year 1921 and the J's It was thus planned to take 4 boats J1, J2, J4, and J5, together with both Platypus and Swordsman to Hobart (J3 and J7 were still in Sydney untertaking refits.) They sailed from their base at Osborne House on the 13th of January to arrive at Hobart three days later. This visit to Hobart of the submarines, their Mother ship and escort Swordsman, with their crews made up of about 500 Officers and Sailors created tremendous interest amongst the people of that city. All ships were able to gain a berth alongside. Hobart has always put out the welcome mat for the ships and their ship's companies of the Royal Australian Navy.

Back in 1921 the Vise Regal Representatives, the Governor of Tasmania and Lady The flotilla left Hobart for Sydney on the 24th. of February, whilst to show the flag in Northern Tasmania, Swordsman, called into Burnie for several days enroute to Sydney. Tactical exercises were conducted with the Fleet over 3/16 March. J2 was unable to participate in any of those exercises as a broken shaft on the starboard side, plus port engine clutch problems, and daily worsening of her battery made it mandatory that she be sent to Cockatoo Dockyard. The remaining boats after spending a month in Sydney for maintenance sailed for Geelong with Platypus in attendance. The scarceness of defence finances now posed the question" Could the Australian Submarine Service survive?" As has happened often in peaceful times since Federation and the birth of our Navy, the politicians were squeezing the Naval Board to cut expenditures. It does seem that when from time to time that war arises, then the treasury will somehow find the necessary money to prosecute the conflict. That old axiom, "If you want peace prepare for War." always seems to be forgotten when peace reigns. Whereas the Admiralty had estimated that the annual costs of maintaining a J Class Submarine would be of the order of 28,000 Pounds (this was the figure used by the Naval Board in planning its estimate) the actual cost to refit J3 was now estimated to be 73,500 Pounds, and for J7, 110,861 Pounds. A Naval Committee was now appointed to carry out an inquiry regarding this projected expenditure on J3 and J7, amongst the terms for this inquiry was this interesting one: " You should state to whom, if to anyone, blame is attributable and to what extent," The Committee in its report dated the 15th. of April 1921 indicated that:

When it came to the blame section, the Inquiry Members deftly suggested:

Commodore Dumaresq, Commanding the Australian Fleet, merely forwarded this report to Navy Office without making any comment at all. The inference from this report made it clear a major part of the blame was the responsibility of the Naval Board and senior Dockyard Officers. On the 6th of May, the Naval Board was told no more money would be made available for the Submarine Service in that financial year. A conference convened by the Board included Dumaresq and Boyle, it met on the 12th of May to decide future policy regarding the Australian Submarines, and concluded that Submarines were needed for Australia's defence, and, although the J Class were not ideal, they could, nevertheless, do the job. If not practicable to maintain 6 boats, a lesser number should stay in commission to maintain an adequate trained force to man these Submarines. At Board level it was suggested that 2 J's be maintained and the other 4 be placed in Reserve, but by the end of July, Boyle laid out his plans for the future employment of these 6 J Class. His vision wanted to keep J3, J4, and J7 operational, with J1, J2, and J5 to be laid up in Reserve at Flinders Naval Depot, and the Naval Board approved. One crew would be employed in looking after the three boats slated for Reserve, with an estimated saving of 100,000/ 138,000 Pounds annually. The Cabinet of the Federal Government approved these proposals on the 4th of October and together with Australia, J1, J2,and J5 were paid off. 1921 drifted to a close, not much happening in the reduced Submarine Flotilla of 3 boats, except their noticeable deterioration. Work placing the 3 Submarines at FND into Reserve, moved on, but slowly. The demise of the J boats from 1922/1930

As the crews from J3 and J4 were needed to assist with the laying up of J1 and J5 at Flinders Naval Depot, the plans to join the Fleet at Jervis Bay were jettisoned. By early March the flotilla was back at Geelong, and finally they were ready for 3 Submarines to go to FND to be placed into Reserve. On the 20th. of March, J1, J4, and J5, with Platypus, proceeded from Geelong to Flinders Naval Depot and secured alongside the submarine wharf, and Platypus then proceeded on up to Sydney for a refit. In April, the First Naval Member was told that his Naval Estimates for 1922/1923 had been slashed by 500,000 Pounds. By the middle of May in 1922, the fate of a Submarine Service for the RAN had been decided, the Submarine Flotilla was proving too costly to maintain, it simply "had to go!" so that the Light Cruiser Squadron of Sydney, Brisbane, and Melbourne could survive, remain viable and in commission. The Submarines would be berthed in pairs at FND to allow their batteries to be unshipped, and for general dismantling, the hulls would then be towed onto the nearby mud. J2, J3, and J7, all arrived at FND, and by August the existence of the Submarine Service in the RAN was almost over. A last minute reprieve in November discussed the practicality of retaining J3 or J7 or both, but in the end the decision to abandon the Submarine Service was retained. Disposal of the J's was approved on the 22nd of November, 1922 and, J3 was the first to go, in February of 1923 she was towed to the Mine Depot at Swan Island in Port Phillip Bay, to be used as a pier and power station, and her hulk is still there today. J7 was withdrawn from the disposals list and was retained at Flinders Naval Depot to run her deisel generators over weekends, as a cheaper source of electricity than running the Depot's steam power plant. Tenders were called for disposal of the 4 hulls, J1, J2, J4, and J5, all of which lay on the mud off the Naval Depot wharf. In early 1924, the highest tender of 10,500 Pounds was accepted, and these boats were removed to dock at Williamstown, here they were stripped. J1, J2, and J5 over May/June 1926, were towed one at a time by SS Minch down Port Phillip Bay to deep water outside the heads, and then all sunk. J4 had sunk alongside the Outer West berth at Dock Pier Williamstown, on the 11th. of July 1924. Although the hull was technically owned by Melbourne Salvage Syndicate, the Commonwealth was removing fittings of value, and neither party wanted to accept the responsibility for removing the sunken hull. It took until 1926 to get some action, when Melbourne Harbour Trust tendered to have J4 raised, and this was achieved on the 6th. of December, and she was docked at Williamstown, to make sure the hull was secure, the cost: 2,555.80 Pounds. Now followed a dispute as to who was liable for these costs. Counter claims etc. followed, until finality was reached when the Commonwealth finally agreed to pay Melbourne Harbour Trust 1,500 Pounds. On the 28th. of April 1927, J4's hull was taken in tow by SS Minch, for her last voyage down the Bay, through the Rip, to be sunk, joining the graveyard containing her sister boats. The last boat J7, having been built much later than the other J's in the Class, was still in a good mechanical state, but it was finally decided to dispose of her in a similar way to that used for the other J's. However her use at FND was proving valuable and she lived on, owned by Morris and Watts, then was resold to the Melbourne Ports and Harbours Department. In 1930, J7, was finally sunk at Hampton, a Melbourne seaside suburb on Port Phillip Bay, for use as a breakwater, and her final remains can still be seen under the Yacht Club pier at Sandringham. Conclusion AE1 lost with all hands off Rabaul, AE2 placing herself into our history books by her penetration of the Dardnelles at a critical moment in time of that campaign. She was still lost, but fortunately without losing any crew members. Although the British Government and the Admiralty were magnanimous in gifting the 6 J Class Submarines to Australia, one must question if they were really ridding themselves of a potential time bomb. England and Australia were thousands of miles apart for replacement of vital batteries for the J's, these boats had a voracious appetite for both money and resources, given Australia's Dockyards lack of facilities and experience in the maintainence and refitting of Submarines, these boats appear to have been doomed right from the start. Even in the year 2000, the Australian Submarine Service, is still plagued by problems, the Collins Class have inherent design faults, and only the application of thousands of millions of dollars is likely to sort them out. Submarines are a vital part of this Island Continent's Navy with our huge coastline to defend. I believe, we must retain a viable, vibrant Submarine capability as part of our two ocean Navy strategy. Long may we operate an efficient flotilla of Submarines in the Royal Australian Navy. This article is available from: The Naval Historical Society of Australia Inc. AE1, AE2, and J Class Submarines in the Royal Australian Navy as

Back to Submarine index |