|

Marauders of the Sea, German Armed Merchant Ships During W.W. 2

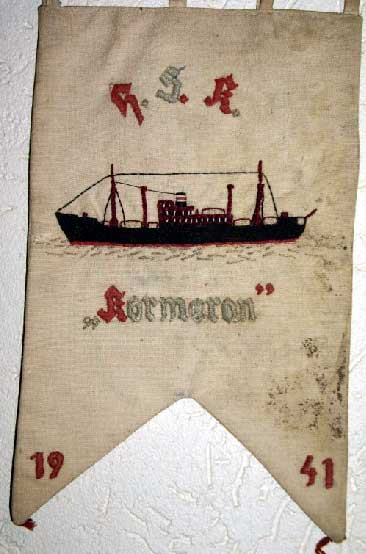

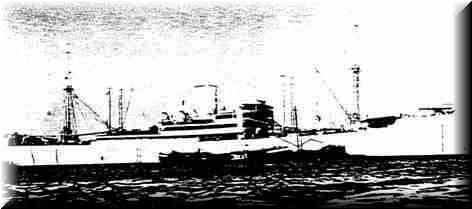

Kormoran and the Sinking of Sydney Kormoran, (Ship 41) "Kormoran" of all the Armed Merchant Raiders, was the largest. She was almost 3 times the size of "Thor," but carried a very similar armament and commenced her nomadic life with 320 mines and had 6 torpedo tubes. Diesel-electric engines gave her a comfortable top speed of 18 knots whilst 2 Arado seaplanes increased her range of vision, and finally she carried a small torpedo boat. Her Captain was but 38, the youngest of all the Raider Commanding Officers. Theodor Detmers had joined the Navy at age 19. (21) After "Widder" arrived home, both her Commander Ruckteschell and Detmers exchanged thoughts on operating a Raider. They believed the better way to break out into the Atlantic was via the Straits of Dover and the English Channel - rather than proceeding North via the Denmark Straits, which at that time of year were usually under the threat of ice. But when the time came for 'Kormoran" to leave, no surface escorts were available for the Channel run, and the Northern route was not judged to be impassable, so that route was selected. 'Kormoran" was disguised as a German warship, having dummy wooden guns in place, plus blue/grey paintwork to be completed. Supplies loaded on board included 28 torpedoes, 400 rounds of 4.1 inch and 300 rounds of 20mm, all destined for 2 U-Boats. Control had decided that Detmers would operate in the Indian Ocean, Australian and African waters, with the South Atlantic or Pacific Ocean as alternatives. He was to sow Magnetic mines off the East coast of Africa, and around Australian and New Zealand ports. Finally, moored mines were to be laid in the approaches to Calcutta, Rangoon, Madras, and Sunda Straits. Bad weather prevailed on the way to Denmark Straits, forcing the ship to seek shelter at Stravenger. It was too rough to complete the warship paint design at sea, so "Kormoran" now took on the mantle of the 7,500 ton Russian ship "Viacheslav Molotov" from Leningrad. By the 13th. of December, this latest Raider was free of the ice, and out into the Atlantic- she altered course Southwards, running into a Force 10 gale. When the weather and visibility finally improved on the 18th. of December, smoke was sighted, but avoided, as the ship was yet to reach her operational area. Only the next day, Detmers was told to now consider himself operational, as too many Raiders in the Indian Ocean over January/February were considered to be undesirable. The engine room staff used this quiet time to check out the most economical way to use the deisel-electric motors, these experiments pointed up the fact that right now, without any retuelling, the ship had a 7 month endurance capacity. On the 29th. of December, the Captain, on a day of good visibility sought to extend his horizon by using one of the Arado seaplanes- alas, a faulty winch and a heavily rolling ship combined to damage the aircraft. Into the New Year, on the 6th. of January 1941, the Greek ship "Antonis," carrying 4,800 tons of coal en route to Rosario from Cardiff was stopped - no alarm had been raised, and she was scuttled. A mixed bag was taken on board, the crew of 28, one stowaway, 7 live sheep, fresh foods, documents, and usetul charts, plus 1,000 rounds of small arms ammunition. When darkness was about to fall in the late afternoon of the 18th. of January, a ship was sighted. Detmers sailed to place this vessel against the fading light, but when it grew dark their target started to zigzag. "Atlantis" had captured Admiralty orders which read:- "In order to minimise the possibility of pursuit by Raider or Submarine at night, independently routed Merchant Ships should, when sea room permits, alter their main lines of advance by at least 3 points. (The 360 degree compass is divided into 32 points, thus 3 points would equate with a diversion of 33.75 degrees.) (22)

until approximately 10 miles from their day time track. During this period ships should continue zigzagging whenever visibility is less than 2 miles. A prudent precaution, to assist a single ship to present a more difficult target for either a Raider or U-Boat. Detmers was able to identify this ship as a Tanker in ballast. At a range of 4 miles he fired star shells to illuminate the enemy ship, then opened fire, straddling the target with his third salvo (to straddle a target, means that shells from a salvo bracket the target, falling both short and over.) A distress call was heard:- "RRRR British Union shelled, 26 degrees 24 minutes North, 30 degrees 58 minutes West." Fire was checked, but the Tanker responded with 4 rounds fired from her stern gun, "Kormoran" once more opened fire, now setting the stem section of the Tanker ablaze, her crew left their ship, 28 being saved, whilst 17 of their shipmates perished. SKL had read this distress message broadcast by the "British Union" and now told "Kormoran" to meet "Nordmark," and hand over the U-Boat stores and torpedoes she carried on board prior to departing for the Indian Ocean. Detmers was also instructed to keep clear of "Thor's" arena of action, he was to stay North of the equator, whilst their fellow Raider would stay below this demarcation line. Both were now in the Atlantic Ocean. A large ship was sighted dunng the afternoon of the 29th. of January at 7.5 miles, "Kormoran" just quietly proceeded, allowing the ship to come to them. At 1330 (1.30 PM) Detmers opened fire - the enemy sent off an alarm signal, turned away, but soon stopped, and her crew left their ship. It was the "Afric Star" carrying almost 6,000 tons of meat from South America to Britain. The 72 crew and 2 women and 2 men as passengers were all taken on board the Raider. Slowly the "Afric Star" sank, assisted by fire from the 37mm gun, a torpedo, and 5.9 inch shells. "Kormoran" decide to quickly vacate the scene, as the distress message had been repeated by vessels close by. A Raider could "Live" or "Die" through the medium of a distress signal being jammed on transmission, stopped from being sent at all, or in fact the ship being attacked daring to send out her frantic warning, and being helped by the sudden arrival of a friendly Warship, that happened to be in the close vicimty. Throughout the total war, luck played a huge part in ones survival, was it fate that brought you in contact with an enemy Raider or hostile Submarine? or decided that your course and speed, where you happened to be on the Ocean's surface at any particular point in time meant you avoided the lurking danger of such a threat. To arrive at the intended destination was always a bonus for both ship, and her company. A second victim was found after darkness had descended, at 3,200 yards Detmers used star shells to light up his target, then his larger guns to stop "Eurylochus" another British ship of 5,723 tons. (23) A torpedo quickly sent her to the ocean's depths, 4 British plus 39 Chinese were saved, but 18 British and 20 Chinese seamen were lost. They met with "Nordmark," fuelled, and took on board meat and eggs from the bountiful "Duquesa." By the 9th. of February, Detmers was enroute to the Indian Ocean, they passed another Raider "Pinguin," but disaster struck 2 days later, when bearings in the main engines cracked. 700 kilograms of white metal was needed to effect repairs. Berlin was asked to help, and responded that it would be supplied via a U-Boat and a blockade runner; meantime, stay in the South Atlantic. Running repairs were made, and it was the middle of March before they met U105, only to learn that U124 was carrying the precious white metal from which the new bearings could be cast. They sank a tired old Tanker, in ballast, the "Agnita" and rescued 38 crew, a mix of British and Chinese. From this ship, an up todate chart of Freetown, its swept channels, and mined areas were obtained. copies were made for passing on to the next U-Boats they came across. Usetul enemy intelligence was always sought from ships that were run down, sometimes they were sunk prior to being able to board them, but useful information was often gleaned directly, or from judicious questioning of prisoners taken on board. On the 25th. of March, Detmers sighted a ship a long way off. His engine problems precluded a long chase, he set an interception course, and was able to close to 5 miles before this Tanker, in ballast, signalled an alarm. "Kormoran" attempted to jam the distress signal, and opened fire, although the second salvo was a near miss, it was enough to make the Canadian "Canadolite" of 11,300 tons, stop broadcasting, and stop engines. This nearly new ship had been built by Krupp, and was sailing to Venezuela, this fine prize was much too valuable to sink. Leaving the bulk of her crew on board, Detmers took her Captain, Chief Engineer, Radio Operator, and top Gunnery Rating in "Kormoran" as prisoners, then with sufficient German command personnel, sent her off to Gironde. It was almost two weeks before any other ship was found, it turned out to be "British Craftsman" 8,022 tons, running in ballast from Rosyth, and destined for Capetown. She was carrying a very valuable item, a large anti-submarine net, and the Captain was delighted to be able to deny the authorities at the Cape this defensive equipment. A torpedo had to be used to sink this burning ship, 5 died, but 45 prisoners were transferred to the Raider. On the 10th. of April the 'Kormoran's" radio operator was pleased to take a signal from Berlin to his Commanding Officer announcing to Detmers "You have been promoted from Commander to Captain." Every one was happy with this news. Two days on, and the Greek "Nicolaos" a new ship loaded with timber from Vancouver and going to Durban in Natal, was stopped by gunfire, although it was hoped to take this find as a prize, her bridge and steering gear had been destroyed by the accurate gunfire, it was with reluctance that she had to be scuttled. (24) In mid April, 4 ships came together, "Kormoran," "Atlantis," and supply ships "Alsterufer," and "Nordmark," 75 prisoners were exchanged, stores and ammunition for the 5.9 inch guns were loaded. "Kormoran" took on a black hull, hoping in the future to pass as a Japanese ship, but right now she became the Dutch "Straat Malakka" out of Rio de Janeiro bound for Batavia. "Pinguin" had been sunk, and with "Kormoran" now in the Indian Ocean they made for the Chagos Archipelago, Colombo, Sabang triangle. Now that a mine sweeping force was operating at Rangoon, Detmers decided that it would be a waste of resources to lay mines in that vicinity. With no mine action here, the next target for mine laying was to be off Madras, but a sighting of a possible British Armed Merchant Cruiser put paid to that proposition, and "Kormoran" avoided any close contact by heading South East. Early on the 26th. of June, whilst it was still dark, a faint light and shadow were noted, a warning shot did not bring any reaction. At 3,000 yards a full salvo hit, setting the ship alight, the crew took to the boats, but only 9 from a crew of 34 were saved. It had been the Jugoslav "Nelebif" 4,153 tons, without cargo, only in ballast, off to Mombassa, but never destined to arrive. That same afternoon, another victim was approached and sunk, the Australian "Mareeba" with a load of sugar for Colombo, a crew of 48, all unhurt, came on board. By the 21st. of July, Detmers decided he would not mine in the Bay of Bengal as Britain had increased her forces in that area, but would cruise in Indonesian waters, then South of Sumatra and Java, continuing down the coast of Western Australia until in the latitude of Carnarvon. At this stage he noted in his diary that the crew were working in watches around the clock, to sieve out worms and beetles found amongst their store of flour. He added "the cook and baker are extraordinarily important in an armed merchant-cruiser, and both of them on board deserve boundless recognition." This comment by the Captain serves to highlight the fact that it is not only the Army that "Marches on its stomach." Now by the 13th. of August, "Kormoran," had sailed to a position 200 miles Westward of Carnarvon, a ship was sighted at dusk some 10 miles distant. Detmers wanted to stay in touch, in the hope of having a successfiil night action, but when about 7 miles away, it suddenly turned towards them and gave the "QQQ" alarm, not with a position, but with a bearing ~ this made the Raider Captain think that perhaps the mystery ship was in visual touch with other ships, maybe she was "Bait" for a convoy in the vicinity, and was calling up an escort. She was about 6,000 tons, obviously fast, and Detmers decided he was not falling for any possible trap, he altered course Westwards, and then to the South. His diary bears the note: "After 7 weeks to have seen a ship at last and to have had to let her go is very bitter." The Raider made her way up to the Northern tip of Sumatra, giving up any idea of laying mines at the approaches to Carnarvon, not enough traffic about to justi~ the operation. (25) When commenting on "Kormoran's" operations at a later date, SKL, was terse about the fact that mines were not laid, they considered that with little risk to his ship, Detmers could have used an Auxiliary to lay mines, which may well have claimed some victims. To follow Detmers in his successfbl Raider, it is never clear why he always seems to duck the issue of mine laying, and continually rationalises why he did not, or could not, lay a nest of them in any area at all. Pickings were sparse, when only 150 miles South of Ceylon, a fast ship of about 11,000 tons was sighted on the 1st day of September, but she passed too far away for any attack to develop, and "Kormoran" could not match her speed. Eventually she was lost after a rainstorm, and the seaplane could not be used to seek her out again. Detmers lamented in his War Diary "Without a catapult it is a weapon of opportunity which can quite infrequently be employed." I have already noted how much more suceessful "Thor" had been in using its seaplane - one needed the will of both the Captain of a Raider plus his Arado pilot to get this aircraft airborne as often as practicable- this will to use his spotting aircraft, seems to have been somewhat lacking in "Kormoran." SKL now told Demers that they intended to send "Thor" to relieve him in the Indian Ocean by the end of December. Detmers believed that he had a thankless role in this area, he thought Allied ships kept to the Northwards, close to British bases - thus they could only be attacked by a Raider taking a greater risk- and disregarding their operational orders. He thought this was the lesson to learn posed by the sinking of "Pinguin." At last, success! On the 23rd of September, close to the equator, the Greek "Stamatios G Embiricos" of almost 4,000 tons, no cargo, just in ballast from Mombassa to Colombo was caught and scuttled. The crew were taken in "Kormoran," who had now achieved 68,283 tons of shipping sunk from 12 ships. The "Kulmerland" out of Kobe with 4,000 tons of diesel fuel, lubricating oils, provisions for 6 months, and the long awaited white metal, met with "Kormoran" who carried out a self refit in the watery wastes of "Area Siberia" adjacent to the latitude of Perth. All prisoners were also handed over to the supply ship. Detmers command was now stored and fuelled up to the 1st. of June, 1942. Nothing further was ever heard directly from "Kormoran" ever again. His last War Diary sent home in "Kulmerland" indicated "Hope to be in operations area during the new moon period." Dr.Habben, one of the survivors, writing from prison camp told SKL that after writing the phrase above, Detmers had changed his mind- and intended to lay mines off Perth, but enroute, he learned that a convoy was to leave there, escorted by the British 8 inch Cruisers, "Cornwall," and "Dorsetshire," so he decided to move North along the coast heading for Shark Bay. (26) It was not until the 24th. of November, that Berlin heard Sydney Radio ask for "Details of the action and the name of the ship from which survivors came." At the end of November, SKL learned that the Australian Cruiser H.M.A.S. "Sydney" was 6 days overdue at Fremantle on the 26th. of November, returning from convoy duties, and it was believed she had sunk an enemy Raider, but her own fate was still unknown.

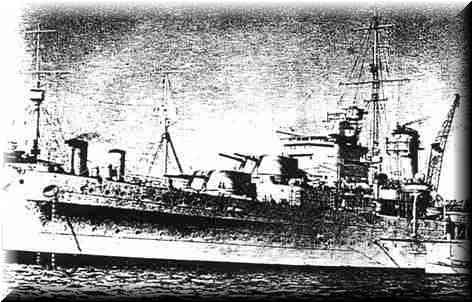

H.M.A.S. Sydney - Missing with all her ship's company, after a battle with the Raider "Kormoran." Then the next intercept read: "A British Tanker has taken German seamen from a raft, and others have been sighted in lifeboats, of which two have arrived in Western Australia. Apparently "Sydney" was on fire when last seen by the Germans." At this time "Kormoran" was the only German Raider at sea, so SKL now realised she had been sunk. It was later, via letters from survivors held in Australia, that the story of what had happened filtered back to Germany, as indicated, the first news came from Dr. Habben, who also indicated that Captain Detmers was also both a survivor and a Prisoner of War. The German story of the light to the end for both "Sydney" and "Kormoran," is all that has ever become available, "Sydney" was never found, vanishing with her total crew of 645 Officers and Sailors. It was about 1600 (4PM) on the afternoon of the 19th. of November, 1941 that a lookout in Kormoran" sighted smoke ahead, it soon became apparent to the Raider's bridge personnel, that this belonged to a Light Cruiser, and it was H.M.A.S."Sydney," already speeding towards them. Detmers ordered a course to turn them away, his ship working up to full speed of 18 knots, the Captain choose to steer against the wind and sea but straight into the sun. "Sydney" followed them at an estimated speed of 25 Knots, and was signalling with a searchlight. (The Cruiser was most likely using a shuttered signalling lamp, there is no provision for using a searchlight as a signalling medium.) "Kormoran" hoisted a Dutch flag, in line with her supposed identity of being the "Straat Malakka." "Sydney" kept up her flashing, and Detmers as usual with Merchant Ships, responded with flag signals, some of which were deliberately garbled, he also hoisted flags meaning "not understood." Time was gained, still "Sydney" did not open fire, but came up astern, within a short distance from the Raider, at about 1.5 hours after first sighting the Australian Cruiser, she was level with "Kormoran" and on her starboard side, less than 1,000 yards away. The Germans felt they were getting away with their deception, and that the Cruiser's Captain believed that he had a harmless Allied Merchant Ship on his hands. "Sydney" had her Walrus Aircraft sitting on the catapult, already swung out in position for launching, suddenly, the catapult was trained in again fore and aft. This seemed to signal a non aggressive attitude from the Cruiser. The Germans also thought that only half the Cruiser's gun crews appeared to be closed up at their stations. (27) "Sydney" now demanded that "Kormoran" give her secret call sign, the bluff could no longer be sustained. " IT WAS TIME TO FIGHT." Detmers ordered his guns unmasked, it took only a record 6 seconds to achieve. Meantime the Dutch flag was being replaced by the war flag of the German Navy, and the Captain's pennant hoisted. Before the war flag was close up, i.e. hoisted to the top of its position, the "Kormoran" opened fire with a single round, it fell short, but the next 3 gun salvo, hit "Sydney's" bridge and fire control area. "Sydney" also fired at the same time as this salvo, but their shot fell well over, hits from the Raider were now scored on the Cruiser's B Turret, blowing away its top, and also damaging A Turret's training mechanisin, thereby freezing any flirther movement. In a Naval ship fitted with 8 guns, it is usual to find them in 4 by 2 gun Turrets, which arc named from the ship's bow, A, and B, both in front of the bridge, the other 2 fitted aft of the malrimast, are named X and Y Turrets. "Sydney" now had half of her main armament out of action. The aircraft's catapult was now swung into the launch position for the second time, but a direct hit soon destroyed the plane. A torpedo from "Kormoran" struck "Sydney" forward of the Bridge, her bows dipped below the water, her speed fell away, and heavy fire from the Raider's anti-tank 37mm. gun, and 20mm. AA weapons swept personnel from the Cruiser's upper deck, stopping AA guns or torpedo mountings from being manned.

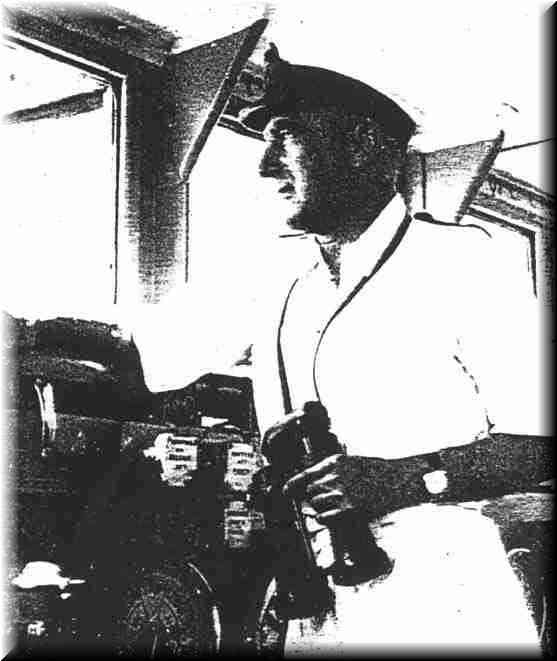

Commander T.A. Detmers, Captain of the "Kormoran" who survived the fight with "Sydney" with 317 from his crew. It was obvious that "Sydney's" fire control system had been put out of action- but her 2 after 6 inch Turrets fired independently and scored 3 hits. These hits, started a large fire in 'Kormoran's" engine room, electrical gear there failed, and all the engineroom staff perished. "Sydney" fell away astern, then tried to ram the now out of control Raider, but 'Kormoran's" number 5 gun kept up firing, "Sydney" turned away, steaming only at 5/6 knots, then fired 4 torpedoes, the closest, missing its target by about 150 yards, as "Sydney" turned, it was evident that her X andY Turrets were trained on her disengaged side, and they appeared to be jammed on their training gear. The Cruiser was kept under continuous fire from the German 5.9 inch guns, and many hits were made on her waterline. The Raider's gun crews reported that during this action they had fired 500 rounds By 1800 (6pm) it was becoming dark, "Sydney's" port quarter was ablaze, and many explosions were heard on board her. Finally, at a distance of 5 miles, she was out of range, and slowly steamed off towards the horizon. For hours, the German crew fought to save their ship, they could still observe the huge fire burning in "Sydney," until about 2300 (11PM) "When it disappeared, most probably, "Sydney" blew up and sank at that time." (28) As all of "Kormoran's" fire fighting equipment had been destroyed, there was little that could be done to quell the formidible fires still raging, Detmers ordered his guns crews to remam, and everyone else to leave the ship Some boats had been destroyed in the action, rafts, and rubber dinghies were utilised. Two steel lifeboats stowed in Number 1 hold were normally launched via auxiliary equipment- but, this was damaged, and these boats had to be manhandled with a great deal of difficulty. The Sinking of "Kormoran."

The German Armed Merchant Raider "Kormoran" sunk in the battle with H.M.A.S. Sydney. Twenty had been killed in the fight with "Sydney," and 60 others drowned when a large rubber dinghie sank when the Raider was abandoned. At 0100 (lAM,) in the early hours of the 20th. of November, Detmers hauled down both his Pennant and the Flag, and embarked in the last boat to leave 20 minutes later, mines on board blew up, and, down went "Kormoran" stern first. The weather worsened, men in boats, dinghies and rafts could not all stay together as a group, one boatload was recovered by a coastal steamer, who broke the news of this engagement to the world. Both the Royal Australian Navy and the Royal Australian Air Force set out to find the survivors from both sides, all the Germans were found, although some took 6 days to reach the Western Auatralian coast line. Not a soul from "Sydney" has ever been found - it appears that Captain Burnett took his Cruiser too close to an apparently harmless Merchant Ship, to be totally suprised, and paid the price.

The following extract was originally published in the Sydney Morning Herald - a German crewman describes Australia's biggest World War II disaster. Children are renowned for asking difficult questions. But Heinz Messerschmidt was unprepared for the question his son was about to ask as he looked up from a photograph of the officers and crew of Austrlia's World War II cruiser HMAS Sydney: "And all these men were killed by you?" he asked. "Yes," said Mr. Messerschmidt, "All of them." As a 26-year-old lieutenant commander on the German raider Kormoran, Mr. Messerschmidt witnessed the murderous barrage that sank the Sydney and led to a mystery that remains today: Why did none of the 645 crew members of the Sydney survive to tell their tale? Mr. Messerschmidt dismisses conspiracy theories of Japanese submarines being involved as "ungrounded speculation and a huge defamation" for the officers and crew of the Kormoran. He explains the mystery with a closer examination of the two main figures involved: Captain Detmers, of the Kormoran, and Captain Burnett, of the Sydney. Mr. Messerschmidt is now 83 and lives in a small, tidy apartment near Kiel in northern Germany. He spent five years in a prisoner-of-war camp in Australia and had many opportunities to rake over the battle with Captain Detmers. A widowerer with neatly combed white hair and a perfectly ironed white shirt, he adjusts his Kiel Yacht Club tie and says: "Captain Detmers was a very strict man who placed great emphasis on dress and abstinence from alcohol. "A month before our engagement with the iSydney, Captain Detmers celebrated his birthday. We were allowed to drink Whisky, and one of the crew members got a bit drunk and let his tongue run loose. "Detmers cut him short straight away, saying that he would like to make something very clear to the assembled gentlemen, and that was that our moment of truth would come when we had a visit from the "Grey Steamship Company', as in the British Navy, and by inference their Australian allies, were referred to. "Then he said no more whisky and that was the end of the evening." Mr. Messerschmidt shuffles his folders and memorabilia relating to the Sydney and looks over his glasses. "And Captain Detmers was exactly right, and not for the first time. He sensed that a visit from the Grey Steamship Company was on the way. "As the Sydney approached, he sensed that they wanted to continue on their southerly course and that they were not prepared for any irregularities. "Campain Detmers said the Sydney would come by, say many thanks, wish you bon voyage and see you later. "He ordered everyone below and said the Sydney would notice nothing and that we would get away with it, referring to the disguise of a Dutch merchant vessel the Germans were using. "He was the right man for an undertaking of our nature, a Himmelsfahrtkommando as our ships were know (suicide mission); he could always sense that little bit more. "Basically, all the survivors from the Kormoran, all of us, must thank Captain Detmers for his finger-tip touch. Without him everything could have run differently from the start." Captain Detmers said right from the first contact with the Sydney that the Australians weren't suspicious. "The Sydney failed to make a thorough investigation of who we were, and came far too close. "You have to picture it. It was late November and the Sydney was in the Western Australian waters; the crew had warred hard in the Mediterranean and had been successful in conjunction with the British Navy. "What should a merchant raider be doing in these waters, so close to the Australian coast? "We had disguised ourselves as the Dutch merchant ship Straat Malakka, and carried a Dutch flag. "A raider simply could not be in these waters "And they must have thought 'But we have the assignment to a least clarify who it is'. The Sydney asked what type of cargo we had, where we were traveling to --- but we didn't have the secret signal and letters [in reply]. "Basically it was this signal that was the death sentence for the Sydney and the cause of this terrible chapter of history for Australia." Mr. Messerschmidt wanders back in time. "As the Sydney approached we could see that they had prepared to send up their spotter plane, which would have given us away because we had a deck cargo of mines. "But then the plane was suddenly put back into its normal position . That was the moment when Captain Detmers said 'Ah yes, it's tea-time on board --- they'll probably just ask us where we are going and what cargo and then let us go on. "Then Captain Burnett of the Sydney made the following mistakes: he came far too close and, worse still, instead of putting himself directly behind us, he put himself directly opposite. "If he has sat behind us he could have used both forward turrets on us an we could not have brought all our weapons to bear on him. He was only 900 meters away. You could see the ship's cook with his hat on at that distance. "We saw that no-one ran around on deck and that they were not alarmed. "Detmers said 'Now comes the good journey etc', but instead come the order to hoist your secret signal. Detmers immediately ordered the camouflage to be dropped and the German flag to be hoisted. "Then, with anti-aircraft guns, we held the bridge under continual fire to put all the officers out of action. "At the same time we fired torpedoes and our six-inch guns. "The Sydney was not ready for battle. The four turrets were not trained on us and the torpedo tubes were not manned. As we opened fire, the crew started running for the torpedo tubes, but we held the torpedo tubes under contant fire with our guns so they couldn't get there. "This is the murderous nature of the attack, when a totally unprepared cruiser lies in such close range to what it believes is a Dutch merchant ship - which within a minute can transform itself into a warship. "The six-inch shells were armed in the base and not the nose, so they went over the short distance and pierced the armour and exploded inside the ship. "It was half an hour of continual fire. It's a surprise no one survived. "The few that did survive the initial onslaught were the firing officer and crew of the rear X turret, who fired three times and hit us in the magazine, once amid ships and the third time through the funnel, which was used to pre-heat the oil before it was pumped back down into the motors. "You can picture what happened as the hot burning oil flowed back down into the engine room. Only one man survived. Then we had no power and could not put the fires out. "It was then we realised it was all over for us. We would have to abandon ship and would be picked up as prisoners." Heinz Messerschmidt flicks through carefully arranged photos and reveals the stranger side of his encounter with the Sydney. "In the mid 1930's I was a midshipman on a training cruise and we were docked in Cadiz in Spain at the same time as the Sydney. The photo here is the Sydney. It was docked opposite and both crews made tours of the respective ships. I went on board the Sydney and met come of the crew and took some photos of them." He shuffles his memorabilia and extract another small photo with a large Australian face beaming across is and the words HMAS SYDNEY clearly emblazoned on his cap. "I don't know who this man is, nor if he was on the Sydney at the time of the encounter with the Kormaran, but non of us would have dreamt that we were to meet again, and under such different circumstances." Mr Messerschmidt pauses. His memories of Australia are full of warmth towards the Australians who treated him so well, not only as a prisoner-of-war but also as a tourist and guest of the RSI. "You all make so much effort to find another answer as to the fate of the Sydney," he says wistfully. "This is everything I have collected over the years on the Sydney and Kermoran. I gave back my Iron Cross to one of the prison guards in Australia just before we were shipped back to Germany on the Steamer "Orontes." An then there was a final twist in the tale; the ship lying next to the Orontes in Port Melbourne was the real Straat Malakka.

LOST AT SEA 19TH NOVEMBER 1941 HMAS SYDNEY - THE OFFICERS Commander Edmund Wybergh Thrushton DSC RN Chaplain the Rev. George Stubbs RAN Lieutenant Thomas Garton Brown RAN Sub-Lieutenant Albert Edwin Byrne RANR Sub-Lieutenant Bruce Alfred Elder RANR Gunner Frank Leslie Macdonald RN Acting Gunner John Kerr Houston RAN Warrant (E) William George Batchelor RAN HMAS SYDNEY - THE CREW B C D E F G H I J K L M N O P Q R S T U V W Y Z next chapter |