|

The Laconia Incident

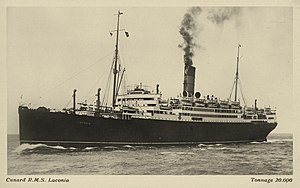

The story of the Laconia Incident began on the morning of September 12 1942. U-156 was on patrol in the South Atlantic, off the bulge of West Africa, midway between Liberia and the Ascension Island. Commanded by KL Werner Hartenstein, she was one of the many Type IXCs stationed along the west coast of Africa. While heading southward on the surface, the cry of a lookout brought Hartenstein to the bridge of the U-boat. Their attention was fixated on the silhouette of a large British ship, sailing alone in the distant horizon, southwest of their position. That location was about 500 miles off the African coast and at an area frequently patrolled by allied planes based out of Freetown. Hartenstein altered course to run parallel with the ship, keeping the smoke in sight and staying far out of sight until he could close the gap when night has fallen. He would soon learn that his target was the 20,000 ton British Cunard Star Liner, Laconia. At the outbreak of war, the Laconia had been converted into a troopship, armed with deck guns, depth charges and asdic equipment. This made her a legitimate military target. U 156 As soon as sunset approached, Hartenstein closed his target and by 10pm, U-156 was in position. With the allied ship in his crosshairs, he fired two torpedoes from a range of about two miles. After a run of about three minutes, both torpedoes found their target and almost immediately the Laconia stopped dead in the water and began to list. Hartenstein surfaced and made his way to the stricken ship to try to capture senior military officers. In the fading sunlight, crew members of the U-156 could see survivors struggling in the water, some in lifeboats, but many in the sea. The scene was in total chaos, with burning wreckage lighting up the night sky, there were floating corpses, overcrowded lifeboats, frantic swimmers and panic cries for help. As he approached the beleaguered survivors, the crew of U-156 was astonished to hear the sounds of Italian voices. “Aiuto, aiuto”, the cries for help in Italian. Puzzled, he takes on a few survivors and soon discovers the true situation aboard the Laconia. As it turned out, she was carrying 2,732 passengers; 136 crew, 285 British soldiers, 80 civilians including women and children, 160 Polish guards and 1,800 Italian prisoners of war. It was not the troopship that he had imagined. Realizing his error, Hartenstein immediately launched a rescue operation. Hundreds of survivors were picked up, including civilian women and children, with many crammed inside the submarine, on the upper deck and a further 200 survivors in tow aboard four lifeboats. He also called for assistance from nearby U-boats and broadcasted a radio message in plain English, providing his position and requesting aid from any nearby vessels, promising a suspension of hostilities while rescue operations were underway. U-156 remained on the surface for two and a half days providing aid to the beleaguered survivors. Meanwhile, back in U-boat headquarters in Paris, Donitz was startled by Hartenstein’s actions. Although he ordered for no such rescues to take place, this time he not only allowed it, but nevertheless supported it. Donitz would explain many years later, “to give them an order contrary to the laws of humanity would have destroyed it (the crews morale) utterly”. Lieutenant Commander Hartenstein and his crew of U-156. U-506 (Erich Wurdeman) joined in the rescue Erich Wurdeman of U-506 arrived two days later and joined in the rescue. To speed up the rescue operation, he ordered three more U-boats to speed to Hartenstein’s aid. Flying the Red Cross flag, U-506 (Erich Wurdeman) and U-507 (Harro Schacht) arrived two days later, just around noon of September 15. They were later joined by an Italian submarine Cappelini. These four submarines shepherded the survivors, with lifeboats in tow and hundreds standing on the decks of the U-boat, they made towards the African coastline for a rendezvous with Vichy French warships dispatched as part of the rescue.

The next morning, September 16, at 11.25am, this concentration of U-boats was spotted by an American B-24 Liberator bomber operating out of Ascension island. The survivors waved and the U-boats signaled for help. As Red Cross flags were draped over their decks, the pilot Lieutenant James D. Harden turned away and radioed back to base for instructions. The officer on duty that day Captain Robert C. Richardson III replied with the order to attack. Half an hour later, Harden flew back and the survivors felt a sigh of relief on seeing the returning aircraft. They had expected a drop of supplies, of the much needed food and medicine. Instead, they were attacked with a concentration of bombs and depth charges. One bomb landed amidst a lifeboat and hundreds perished during that attack. U-156 was slightly damaged and forced to submerge, leaving hundreds of victims struggling in the water. All the submarines dived and escaped, although U-506 and U-507 returned to the area later, unwilling to desert the people they had saved. Fortunately, Vichy French warships from Dakar arrived the next day and picked up the remaining survivors, so the loss of life from the American action was contained. In total, there were about 1,621 deaths with 1,111 survivors, including those already taken aboard the overcrowded U-boats. This incident left a foul bitterness in the U-boat war that would cast a long shadow over Donitz and his seamen. The action of Captain Richardson was considered by many as a war crime, although no formal charges were ever placed. As a result of this incident, Admiral Donitz issued an order forbidding U-boats from attempting any rescues and furthermore, from providing any assistance whatsoever to survivors of submarine attacks. He was quoted to say “no attempt of any kind must be made to rescue the crews of ships sunk”. This order became to be known as the “Laconia Order”. Up until now, it was common for U-boats to aid survivors of their attack by providing provisions and pointing out the direction closest to land. Despite the order, some U-boat commanders continued in their practice to aid survivors of their attacks. After the war, Donitz stood trial for war crimes and the Laconia order was used as a basis of indictment against him. Most surprisingly, he received support from some of the most respected figures in the US Navy, Admital Chester Nimitz who came to his defense and said that the United States had operated under the same engagements of unrestricted warfare. Despite the evidence of allied practice, Donitz was convicted of war crimes by the Nuremberg Tribunal and sentenced to 11 and a half years in prison. The U-boat crews deeply resented this action and felt that they were being prosecuted for the threat they had posed to the allies rather than for war crimes. I acknowledge the U-Boat net for the Laconia story. |