|

The Golden Cruiser. HMS Edinburgh sunk in WW2, carrying 5 tons of Russian gold with her

The cruiser HMS Edinburgh was laid down on the 30th. of December 1936 at the Swan Hunter yard at Wallsend. She completed on the 6th. of July 1939, ready to take part in WW2, having been launched on the last day of March the year before. When I was a Midshipman in HMAS Australia, and we joined the Home Fleet at Scapa Flow in mid 1940, Edinburgh became part of the 18th. cruiser squadron later that year.

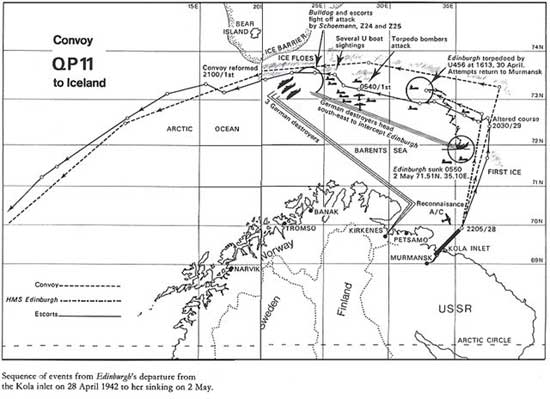

HMS Edinburgh sunk during WW2, whilst carrying In November 1941 she was escorting Russian convoys, then as part of the Navy covering a returning convoy, QP 11, from Russia, she sailed from Murmansk on the 29th. of April 1942, two U-Boats, U-436 and U-456 weree lying in wait for QP 11, they sat on the 73rd. parallel of latitude in longitude 33 degrees East. On the 30th. U-436 loosed off a salvo of four torpedoes, all missed Edinburgh, but at 1615 ( 4.15 PM ) two fish from U-456, attacking the cruiser from her starboard side, rammed home, one entered the forward boiler room, extensive flooding resulted, the second torpedo, hit aft, blowing's the cruiser's stern off. It destroyed the rudder, made the two inner shafts useless, and the quarterdeck was folded back over the aft Y turret looking like an opened top of a tin of sardines. The asdic operator on watch had reported a contact shortly before this devastating attack, it is alleged he was told to disregard it by his superiors. A very grievous error on someone's part! The Captain of U-456, having exhausted his torpedo outfit, could only watch impotently, as the stricken cruiser limped off towards Murmansk under her two outer screws. With the torpedoing of Edinburgh, two destroyers, Foresight and Forester, plus two Russian destroyers were detached from the convoy screen to go to her assistance. The two U-Boats shadowed , and reported their success to base, although in general, the Kreigsmarine faced a fuel shortage, Navy North despatched three destroyers, Hermann Schoemann, Z24, and Z25 on the 1st. of May to the scene, they headed off north-north-west. QP 11 had turned westwards and was some 150 away from Bear Island, just as the arctic night slowly turned into a pale daylight, six JU 88's flew in from the south. The British corvette Snowflake, turned to face the aircraft and engaged with her 4 inch , two Lewis guns and her pom pom. The attack failed , but I believe it did mark the first time aerial torpedoes were used against one of our Arctic Convoys, but the torpedoes were all dropped prematurely. The convoy ran into a waiting U-Boat on the surface, and it was forced to dive, the ships turned firstly to port, then another change of course to the north, this latter move took the convoy into the proximity of the ice. At 1345 ( 1.45 PM ) Snowflake picked up three distinct contacts on her radar all to the south, the destroyer Beverley soon identified these echoes as enemy destroyers. The convoy was ordered to make smoke and turn away to starboard, at about 1400 ( 2 PM ) a submarine was sighted from the convoy, and yet another turn to starboard was made, as the ships continued to edge into the ice. Fire was briefly exchanged between the British ships and the more heavily armed Germans, torpedoes were set on their way by both sides, but all without result. The British ships fell back to reinforce their convoy, as a Russian freighter Tsiolkovsky straggling behind was caught by a torpedo, and she quickly sank, and the trawler Lord Middleton came back to search for, and rescue survivors. The German destroyers now launched another attack against QP11, this time coming in from the south-south-east, they were detected at a range of 8.5 miles, this range reduced by 2 miles, as both forces re-engaged at 1410 ( 2.10 PM. ) This brush lasted a bare five minutes befor the German commander Schulze-Hinrichs withdrew. The British naval forces now closed towards the convoy, as reports had been received that two enemy submarines awaited the exit of the convoy from the shelter of the ice cover. The escort commander was faced with a dilemma, to stay in touch with QP11 in the ice leads, but to retain manoeuverability, he did not believe that the German destroyers had really given up. He was spot on, at 1600 ( 4 PM ) the enemy was sighted at 6 miles coming in from the east-south-east. Again the stiff resistance put up by the lighter British ships paid off, although Bulldog, suffered splinter damage, after only 10 minutes, again the Germans hauled off and made to the south. By now the convoy had stretched out to cover over seven miles, the screen needed to be on their mettle to protect them all over this distance. In another half hour, once more the German ships at 12 miles away were taken under fire, after a short seven minutes again they withdrew under cover of their smoke. No hits had been made, and all these cat and mouse encounters were running down the ammunition stocks, and thus far the German tactical commander had been unable to carry out his orders and attack the seriously damaged Edinburgh. Fifth and Final Attack. After three hours, the screen commander reckoned he had seen the last of the enemy destroyers, and he rejoined the convoy now breaking clear of the ice burden. By 2200 ( 10 PM ) the two shadowing U-Boats gave up as the escort rejoined, and PQ 11, Reformed, and now made 8.5 knots to the west. By 0700 ( 7 AM ) on the 7th. of May, the escort departed to refuel, now with friendly aircraft overhead QP 11 was safe, and it finally arrived at Reykjavik, its ordeal over. Back to Edinburgh. This ship carried Rear Admiral Bonham-Carter, now with his flag Captain H.W. Faulkner, they surveyed the damage caused by the German U-boat torpedoes, but an added burden confronted them both. In one of the ship's magazines, 5 tons of Russian gold had been loaded from a heavily guarded lighter before they sailed. Purporting to be ammunition boxes, this pretence was soon aborted, as stencilled water painted marks on the boxes soon were washed away by the sleet falling at the time, dripping red splashes onto the slush covered deck. One of the Royal Naval sailors sweating over loading these heavy boxes remarked to his officer: "It's going to be a bad trip, Sir! this is Russian gold, dripping with blood." Quite a pronouncement as it all turned out in the end. This gold with a value at that time, of 45 Million Pounds sterling was destined for the United States Treasury, being part payment for all the munitions and materiel despatched to Russia from America. Once all the watertight doors were closed, the ship could steam at about 8 knots, but there was a distance of 250 miles to negotiate to safety, chaos reigned on the upper deck. The bow was some seven feet deeper than normal, with huge amounts of water rushing in and out of the gash in the hull, without a rudder, the cruiser was unmanageable. The ship was covered in ice, listing, and as reported, her stern a total shambles. None the less, it was decided to attempt to take her under tow, a tough evolution in even ideal conditions. With great skill and seamanship, Lieutenant Commander Huddart brought Forester in under the cruiser's bow, a line was passed, to it attached a heavier hawser, it was necessary for one of Edinburgh's anchors to be secured as a dead weight in the bight of this hawser, the slippery ice on her decks prevented the anchor being used in the manner needed for the tow to be successful. The tow started, the total dead weight of the cruiser slowly gathered way, she turned into the wind, and without a rudder, suddenly cut across the destroyer's stern and the tow wire parted. The two ends of this wire hawser came flying back over the decks of both ships like a vicious snake making its deadly strike. There is nothing much more frightening than being on deck in the path of a parted wire, the recoiling hawser can cut a sailor in two if it strikes him. Three more time a tow was passed and the strain taken by the towing destroyer, alas, the same result each time, for the time the tow was abandoned as a surfaced U-Boat some four miles ahead needed to be driven below the surface and attacked by the destroyers. Now a different approach was tried, Foresight came up on the Edinburgh's quarter, and a line was passed through the destroyer's bull-ring, she now acted as a drogue, and kept the cruiser more or less on course. The squadron staggered along at about 3 knots on a south- easterly course. At 0600 (6 AM ) on the 1st. of May, the two Russian destroyers reported they needed to leave as they were running out of fuel. The Admiral was well aware that his beleagured force was at the mercy of encircling U-Boats, emulating a pack of wolves about to close in on their intended victim. The tow was cast off, and Foresight ordered to join her sister ship in screening the cruiser from ahead. Steering with only two outer screws, was both very difficult and maddenly slow, the prevailing wind on her port side caused the ship to to regularly turn to port, this necessitated in going astern to counter this movement to port. Progress ahead was very limited, and the leaking oil marked her tortured movement, sometimes out of control, the cruiser swung in a complete circle. For almost a day some progress was made, and at 1800 ( 6 PM ) a Russian patrol vessel Rubin, arrived, then at midnight up came a Russian tug and some minesweepers all from the Kola base. The tug passed a tow, and with HMS Gossamer secured to the port quarter, some way was made to the south-south-east. With the dawning of the next day it seemed that despite all odds, maybe the cruiser with her crucial cargo of gold might be saved after all. The refueled Russian destroyers were expected to reinforce the anti-submarine screen, but they just failed to show up. Now unidentified ships were seen to approach through the snow falls, the three German destroyers at last had picked up their target, the crippled Edinburgh. The minesweeper Harrier, Foresight and Forester, all turned towards the oncoming enemy and the German ships were turning so that they could let loose a torpedo salvo. Edinburgh was suddenly obscured by a snow shower, now as Herman Schoemann cleared the snow, she was very close to the disabled British cruiser, the crews at the torpedo mountings had to reset them to cope with the close range. Now the cruiser erupted with both flash and noise, as her main armament took on the fast approaching German destroyer, shells splashing close to her stern. Bonham-Carter had quickly ordered the tow to be cast off, but Edinburgh started to move erractically, in random and very unpredictable circles, she became a difficult target for the German torpedo crews, and equally made it well nigh impossible for her own B turret crew to engage the enemy. Three times she completed a circle, not withstanding her antics, her second salvo arrived squarely on board Herman Shoemann, stopping her dead in the water, as her engines and electrical supply were knocked out. Her Captain, Henrich Wittig ordered smoke be made, and said " the worst luck that could possibly have overtaken us." The plight of this German ship now of course dictated how her fellow destroyers could act. Both Foresight and Forester took on the Germans at about a range of 3.5 to 4 miles away, just as the latter swung to fire her torpedoes, she was hit with three by 5.9 shells from Z25, the breech was blown off X gun, the bridge, No 1 boiler room and B gun all badly damaged. Her crew trying to save their ship, fires ablaze amidships, noted torpedoes from Z24 passed under their vessel. Meanwhile, Herman Shoemann was in dire straits, secret documents were destroyed, and preparations were made to blow up the ship. Forester fired torpedoes at the stricken Hermann Schoemann but they all missed, now the British destroyer came under intense fire from both Z24, and Z25, and four shells struck home, one demolishing No. 3 boiler room, with but only one gun still serviceable, the ship shuddered to a stop. Z24 went alongside Hermann Schoemann to take off her crew including the wounded, at 0830 ( 8.30 AM ) she disappeared beneath the sea. Z25 had fired torpedoes at Edinburgh, and she was struck on the port side almost opposite her first torpedo hit, the cruiser was now open from side to side and could break in two at any moment. She lost way, was listing to port, her guns now no longer able to be laid upon the enemy, and Gossamer was ordered alongside to take off the wounded and Merchant Navy personnel, who were survivors from ships sunk enroute to Russia. Bonham-Carter ordered his flag Captain Faulkner to abandon ship. The Germans had disabled the two British destroyers, given Edinburgh her death blow, the advantage now having passed to them, but due to their preoccupation with removing the crew from Hermann Schoemann, they were blissful about the fate of the British cruiser, and failed to seize the initiative. Forester had been able to get their engines moving, and the Germans were concentrating on Foresight, but her consort was able to screen her with a smoke screen, and the two German destroyers now withdrew at speed to the north west, having picked up some 200 survivors from Hermann Schoemann, but leaving another 60 German sailors on life rafts. Later in the afternoon, U-88 came upon them to pluck them all from their predicament. Bonham-Carter hoisted his flag in Harrier, who had 350 from Edinburgh on board, another 450 were in Gossamer. Edinburgh was still afloat, and the Admiral ordered her to be despatched by a torpedo, she too slid into the depths of the Barents Sea joining the German Hermann Schoemann. From Edinburgh, from her company of 760, 57 officers and sailors died, another 23 were wounded, from the two British destroyers, 21 were killed and another 20 wounded. In Foresight, three merchant sailors from Lancaster Castle and her Master, Captain Sloan had died in the running battle, having survived the sinking of their own ship, only to die on board this British destroyer. The small mine sweepers stuffed full with survivors, the two battered destroyers now laid a course for the Kola Inlet, Admiral Bonham-Carter quite suprised that the German force did not molest them enroute, he had expected that superior force had it acted more boldly would have totally destroyed his force, but to lose Edinburgh with her precious gold cargo was bad enough. There is some evidence that the German Schulze-Hinrichs believed that the Halcyon-class minesweepers were in fact destroyers, given the poor weather conditions and the bold way they were driven, perhaps this is understandable. If the Russian ships Gremyashchi and Sokrushitelni had rejoined after their detachment to refuel, it seems likely that the three German destroyers would have been driven off and Edinburgh might well have survived, but it was not to be. When arriving at Kola on the 5th. of May 1942, Rear Admiral Bonham-Carter moved his flag from Harrier to the patched up Trinidad. She could steam at 20 knots, and sailed out of Kola on the 13th. of May with the destroyers Foresight and Forester, both having been repaired temporarily, Matchless and Somali were added to the escort. The promised Russian air cover did not turn up, and the lone air support was three Hurricanes, on the next day, only 100 miles on the way home, German air reconnaissance found the British ships. At 2100 ( 9 PM ) Trinidad's radar found waves of aircraft coming in from the south and the south-east at a distance of 60 miles, the screen was choked with aircraft. A sense of foreboding swept through the cruiser, she carried survivors from Edinburgh, and merchant sailors who had been sunk, plus Poles who had been sunk. At 2200 ( 10 PM ) the first JU88's fell upon Trinidad and the destroyers, a furious AA barrage met them, no hits were achieved by the attackers, but many near misses resulted. At 2237 ( 10.37 PM ) the Heinkel torpedo bombers joined the affray, the intense fire from the British destroyers forced them to abort, and go after the cruiser, eight let go their deadly cargo of torpedoes, but adept ship handling by Captain Saunders had them pass harmlessly down both sides of his command. A moment later a lone JU88 let go a cluster of four bombs, the starboard pom pom shifting too late to this latest menace, Trinidad was turning to port evading three torpedoes on her starboard side, the four bombs went off with dreadful effect. One missed, but blew up under the port side of the bridge, ripping off plates and flooding compartments below B gun. A second bomb went through the Admiral's sea cabin, on through several compartments to blow up in the mess decks and open up the port side of the ship, the last two bombs had exploded outboard, showering the ship's side with splinters admitting the sea, and shook apart the repairs made at Rosta, the wounded ship began to settle by the bow as water rushed into her. Too late the starboard pom pom shot down this JU88. The ship developed a 14 degree list to starboard, but was still able to make 20 knots, the Walrus aircraft ablaze in its hangar. A gun was out of action, but B gun still operable. Counter flooding reduced the list, but increased the dip of the bow, by 2330 ( 11.30 PM ) the enemy aircraft had departed, but Trinidad had become untenable, it was time for Bonham-Carter to abandon yet another of his flagships, Matchless edged alongside, taking the walking wounded and stretcher cases, now it was the turn of the other destroyers to remove the crew. To the amusement of many, the Captain's steward leapt off the steeply canting deck clutching his Captain's No. 1 uniform intact on its hanger. The Commander, the Admiral and finally Captain Saunders left, HMS Trinidad was abandoned. Bonham-Carter ordered Matchless to sink her, and three torpedoes crunched into her starboard side, she shuddered, and at 0120 ( 1.20 AM ) on the 15th. of May 1942, sank, finally out of her misery, one more victim of the notorious Arctic run to Russia. The destroyers made off to the north, on the deck of Somali, a small figure, in a large duffle coat covering any sign of a uniform, was amongst a group of ratings, sucking on a cup of boiling hot tea,

But it was not yet all over, JU88's again attacked, but to no avail. It seemed they were to meet heavy German units, but fortunately they became Rear Admiral Burrough's cruiser squadron. HM ships, Nigeria, Kent, Norfolk and Liverpool. Still more JU attacks, some 25 dived bombed the combined force without any damage, the destroyers made it back to Scapa Flow to transfer the wounded to hospital ships, and the fit to the Firth of Clyde, the ordeal at last over, until the next time ships needed to be escorted off to Russia. Gold finally recovered from HMS Edinburgh. The full story of the trials and tribulations of recovering this treasure from the cold depths of the ocean north of Russia is another story in its own right.

Map showing HMS Edinburgh's track from leaving

|