|

The Battle of Quiberon Bay November 20, 1759

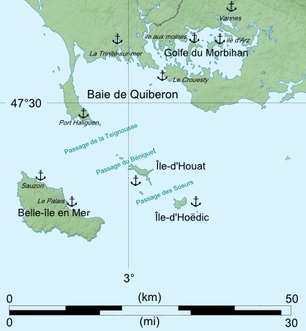

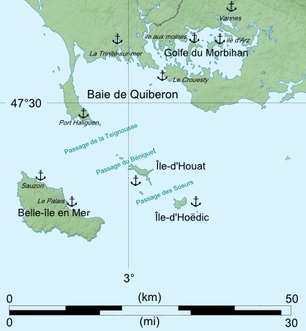

Map Quiberon Bay

It was during the Seven Years war between England and

France that the

Battle of Quiberon bay was fought on November 20, 1759.

The opposing forces were Admiral Sir Edward Hawke with 23

ships of the

line versus Marshal de Conflans with 21 ships.

At the time it appeared France was preparing to invade

both England and

Scotland, with both troops and their ship transports

massing around the

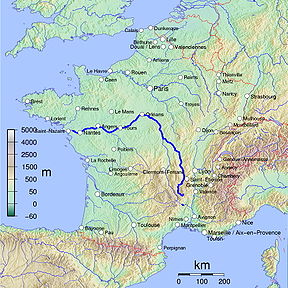

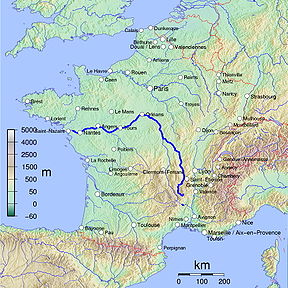

Loire estuary. The Loire river is the longest in France,

rising in the

Cevennes to debouch into the Bay of Biscay.

Loire River

At the Battle of Lagos on August 19, 1759, the French

Mediterranean Fleet

had suffered a defeat at the hands of the British Admiral

Edward

Boscawan thus thwarting French plans to invade both

Britain and

Scotland.

The French Fleet bottled up at Brest by the Royal Navy

blockade was

ordered to break out and collect the French transports at

the Gulf of

Morbihan in Southern Brittany.

The weather was gale force and tended to favour the

British, as Admiral

Hawke took his ships southward to try and prevent the

French breaking

out from Brest.

He found the French some 20 miles out to sea, and ordered

a general chase.

de Conflans then sought the santicty of Quiberon Bay.

With such wild weather prevailing the French Commander

reasoned that

Hawke would not follow, and that his 21 ships would be

safe, but he had

not reckoned on the boldness of his advisary.

Battle of Quiberon Bay. Nicholas Pocock 1812.

National Maritime Museum.

Now allow me to let the words of Admiral Sir Edward Hawke

in his report

to Their Lordships at the Admiralty speak for themself.

The Battle of Quiberon Bay Admiral Sir Edward Hawke

The

Royal George, off Penris Point, 24 November 1759.

Royal George engraved on walrus ivory.

In my letter of the 17th by express, I desired you would

acquaint their Lordships with my having received

intelligence of eighteen sail of the line, and three

frigates of the Brest squadron being discovered about

twenty-four leagues to the north-west of Belleisle,

steering to the eastward. All the prisoners, however,

agree that on the day we chased them, their squadron

consisted, according to the accompanying list, of four

ships of eighty, six of seventy-four, three of seventy,

eight of sixty-four, one frigate of thirty-six, one of

thirty-four, and one of sixteen guns, with a small vessel

to look out. They sailed from Brest the 14th instant, the

same day I sailed from Torbay. Concluding that their first

rendezvous would be Quiberon, the instant I received the

intelligence I directed my course thither with a pressed

sail. At first the wind blowing hard at S. b. E. and S.

drove us considerably to the westward. But on the 18th and

19th, though variable, it proved more favourable. In the

meantime having been joined by the Maidstone and Coventry

frigates, I directed their commanders to keep ahead of the

squadron, one on the starboard, and the other on the

larboard bow. At half-past eight o'clock on the morning of

the 20th, Belleisle, by our reckoning, bearing E. b. N.

1/4 N. about thirteen leagues, the Maidstone made the

signal for seeing a fleet. I immediately spread abroad the

signal for the line abreast, in order to draw all the

ships of the squadron up with me. I had before sent the

Magnanime ahead to make the land. At three-quarters past

nine she made the signal for seeing an enemy. Observing,

on my discovering them, that they made off, I threw out

the signal for the seven ships nearest them to chase, and

draw into a line of battle ahead of me, and endeavour to

stop them till the rest of the squadron should come up,

who were also to form as they chased, that no time might

be lost in the pursuit.... Monsieur Conflans kept going

off under such sail as all his squadron could carry, and

at the same time keep together; while we crowded after him

with every sail our ships could bear. At half-past two

p.m. the fire beginning ahead, I made the signal for

engaging. We were then to the south-ward of Belleisle, and

the French Admiral headmost, soon after led round the

Cardinals, while his rear was in action. About four

o'clock the Formidable struck, and a little after, the

Thesee and Superbe were sunk. About five, the Heros

struck, and came to an anchor, but it blowing hard, no

boat could be sent to board her. Night was now come, and

being on a part of the coast, among islands and shoals, of

which we were totally ignorant, without a pilot, as was

the greatest part of the squadron, and blowing hard on a

lee shore, I made the signal to anchor, and come-to in

fifteen-fathom water.... In the night we heard many guns

of distress fired, but, blowing hard, want of knowledge of

the coast, and whether they were fired by a friend or an

enemy, prevented all means of relief.... As soon as it was

broad daylight, in the morning of the 21st, I discovered

seven or eight of the enemy's line-of-battle ships at

anchor between Point Penris and the river Vilaine, on

which I made the signal to weigh in order to work up and

attack them. But it blowed so hard from the N.W. that

instead of daring to cast the squadron loose, I was

obliged to strike topgallant masts. Most of the ships

appeared to be aground at low water.... In attacking a

flying enemy, it was impossible in the space of a short

winter's day that all our ships should be able to get into

action, or all those of the enemy brought to it. The

commanders and companies of such as did come up with the

rear of the French on the 20th behaved with the greatest

intrepidity, and gave the strongest proofs of a true

British spirit. In the same manner I am satisfied would

those have acquitted themselves whose bad-going ships, or

the distance they were at in the morning, prevented from

getting up. Our loss by the enemy is not considerable. For

in the ships which are now with me, I find only one

lieutenant and fifty seamen and marines killed, and about

two hundred and twenty wounded. When I consider the season of the year, the hard gales on the day of action, a flying

enemy, the shortness of the day, and the coast they were

on, I can boldly affirm that all that could possibly be

done has been done. As to the loss we have sustained, let

it be placed to the account of the necessity I was under

of runing all risks to break this strong force of the

enemy. Had we had but two hours more daylight, the whole

had been totally destroyed or taken; for we were almost up

with their van when night overtook us....

Battle of Quiberon Bay, the Day after.

Richard Wright, 1760.

This battle removed the threat of the French Fleet and any

possible invasion of Britain.

IT WAS A GREAT NAVAL VICTORY.

To quote Alfred Thayer Mahan ( The Influence Of Sea Power

on History )

"The Battle of the 20th of November 1759 was the Trafalgar

of the Seven Years War,

and the English Fleets were now free to act against the

colonies of France, and later of

Spain, on a grander scale than ever before.

For instance, the French could not follow up their victory

at the Battle of Sainte-Foy

( Battle of Quebec ) in 1760 for want of reinforcements

and supplies from France.

So the Battle of Quiberon Bay may be regarded as the

Battle that determined the fate of New France and Canada.

Post the Battle of Quiberon Bay, HMAS Quiberon was so

named to remember that

famous naval victory in 1759.

HMAS Quiberon

Ship Crest

|

|

|