|

A Short Philatelic History of The Yangtze Patrol by George Saqqal

A Short Philatelic History

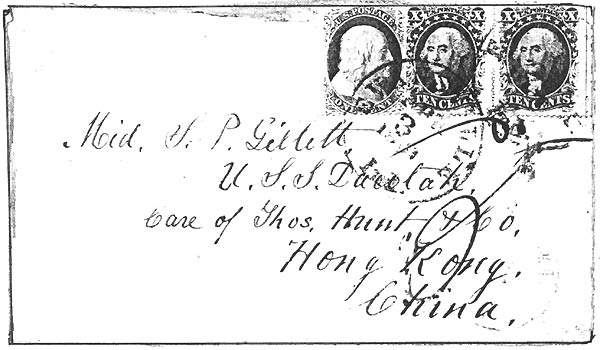

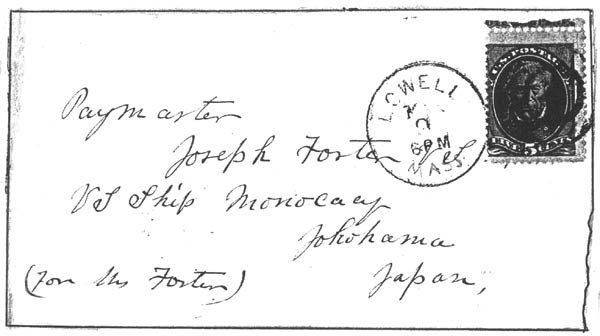

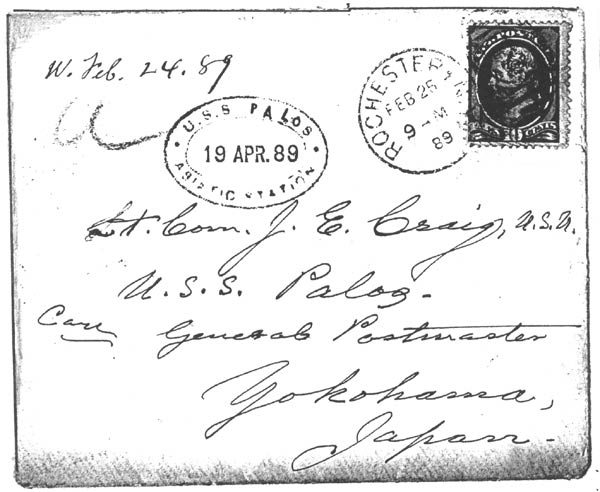

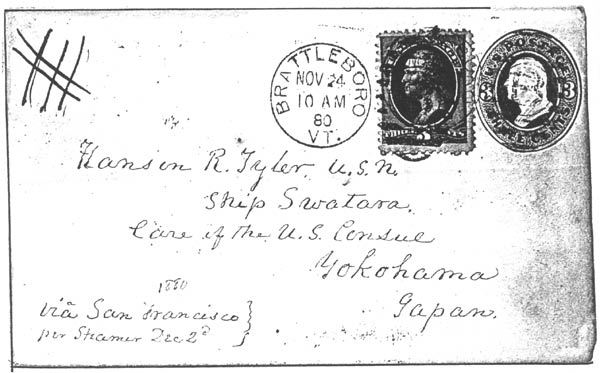

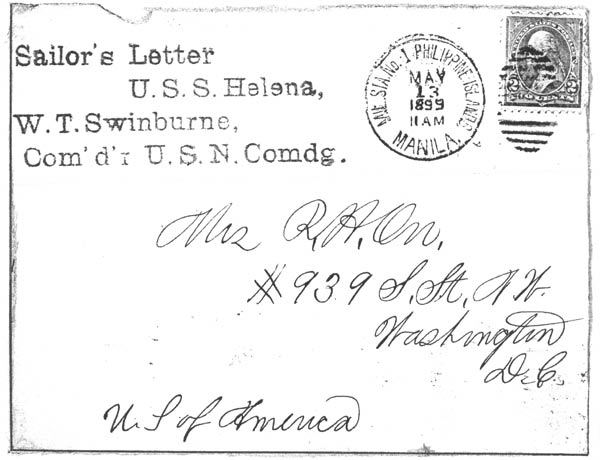

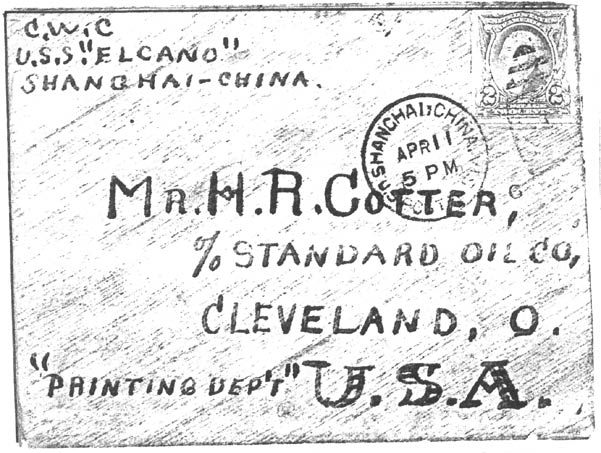

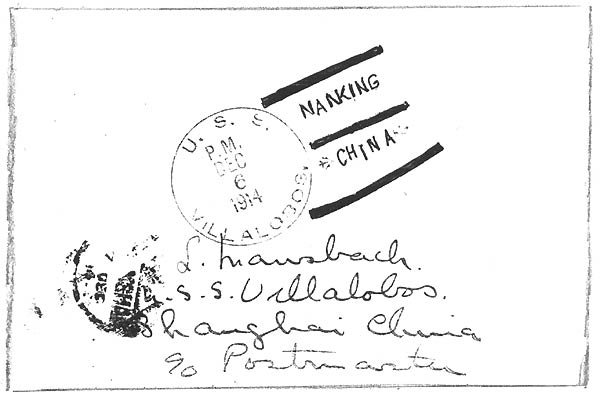

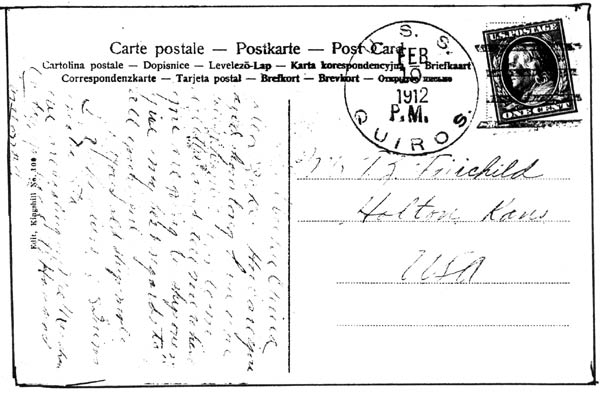

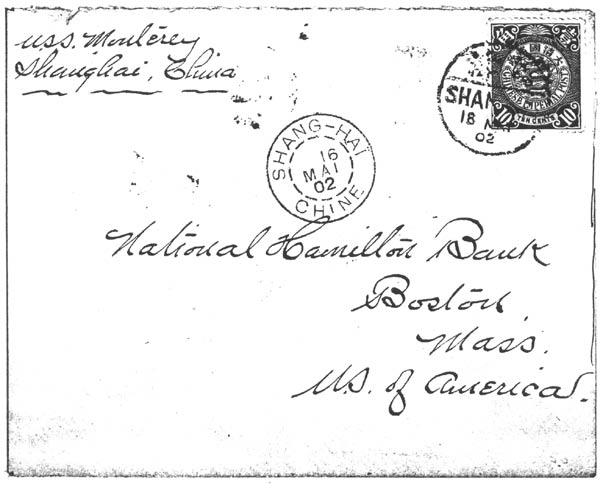

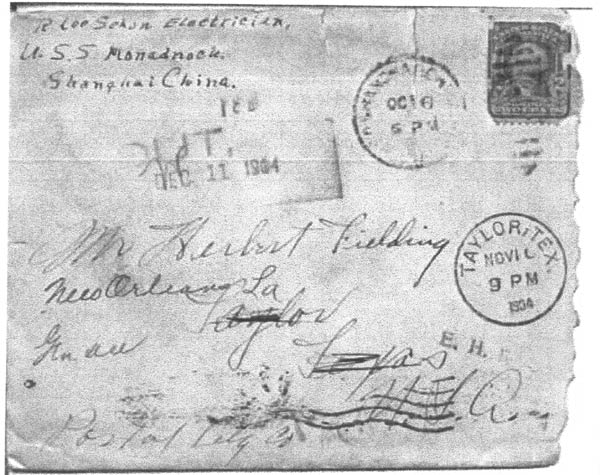

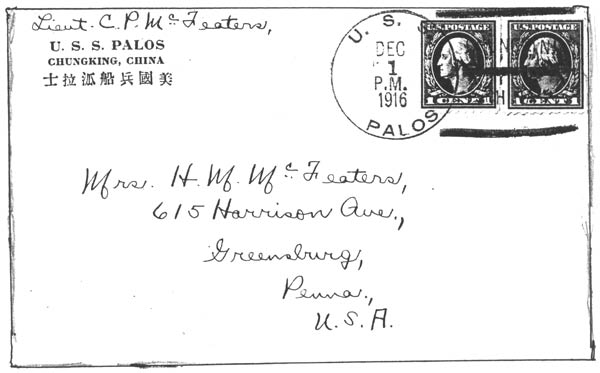

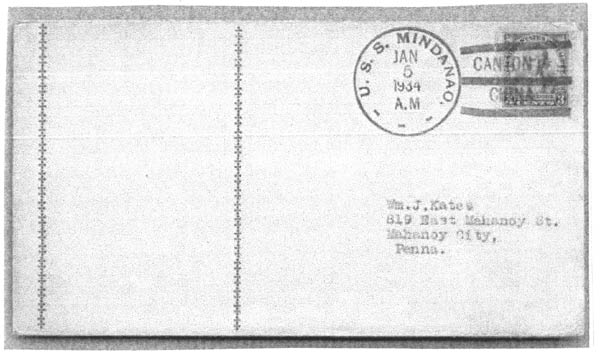

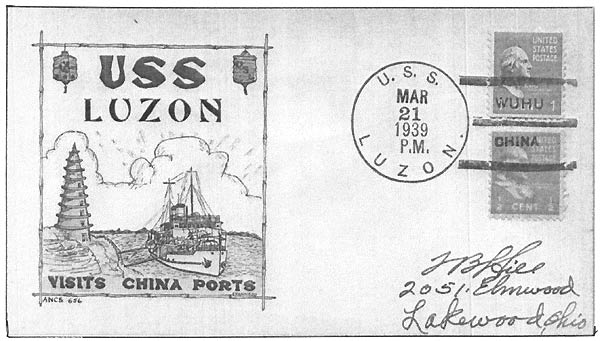

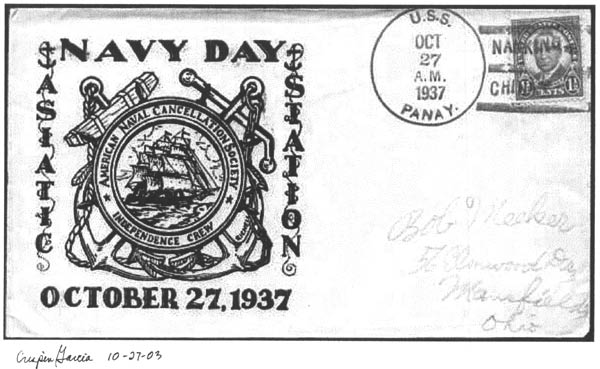

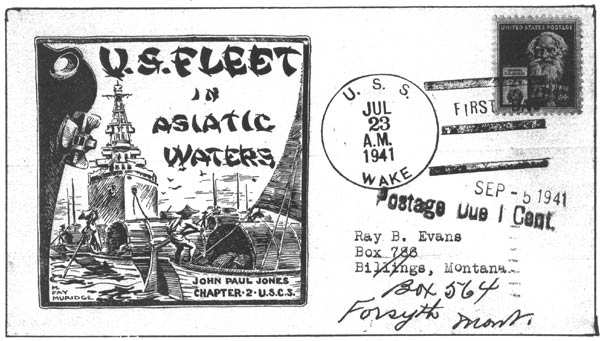

This article first appeared in the February, March, April and May, 2004 volumes of the LOG, the monthly journal of the Universal Ship Cancellation Society The longest river in Asia begins its journey to the sea as a tiny drop of melted snow from Tibet's Geladandong Snowy Mountain, 3900 miles from the East China Sea. Along its course it drains about 750,000 square miles of China on which live about 20% of China's population. The Yangtze Basin grows half of China's grain crops. As long as China has existed, the Yangtze has reflected its past. Often turbulent, rarely placid, always interesting. The Romans knew of China before the birth of Christ, so did the Arabs, and after them the Turks, Venetians and Lombards. When the Roman Catholic Pope sent representatives to the court of the emperor in the Seventh Century he was amazed to learn that a small group of Nestorians had settled there one hundred years previously. When the Nestorians arrived they found a colony of Jews already established in the empire. A millennium later a Jesuit priest treated the Chinese emperor K'iang-hsi's malaria with quinine giving the Jesuits an advantage over other religions whose missionaries sought to convert the 'heathen' Chinese.That particular Jesuit then baptized the emperor's wife, mother and son as well as half his court. There are no figures to tell us if the conversions took or how long they lasted. Still, the country remained a mystery. It fell to the British to open China to the world and they did it with opium. But that came later. Huanghuo Hao Carries The Flag On George Washington's birthday in 1784 the tiny American ship Empress of China (Captain John Green) weighed anchor from New York City with her holds laden with 29 tons of ginseng, $29,000 in silver and an assortment of wooden casks filled with brandy and wine. 128 days and 18,000 miles later she moored in the seaport town of Huangpu 12 miles below Canton on the Pearl River. Captain Green quickly sold his cargo to the local merchants at a hefty 30% profit for his investors. He loaded the Empress of China's holds with tea, gold and porcelain and returned to New York. The Chinese called her the "Huanghuo Hao" Although many ships from America had preceeded her to China, the significance of her voyage lay not in her arrival but in the fact that she was the first American ship to fly the stars and stripes into China. The Chinese dubbed her flag the "Flowery Flag". The British "discovery" of China occurred in 1635, the French "discovered" it in 1698, the Danes in 1731, the Swedes in 1732 and the Russians in 1733. But it was the Portuguese who beat them all. They "discovered" China in 1514. The British success in turning their countrymen into tea drinkers was too much of a good thing gone sour. The British paid for the tea in silver, so much silver that they were running out of it. Someone suggested that the British trade for the tea. The medium of exchange was Indian opium for Chinese tea. It worked to the everlasting detriment of China. The balance of trade always favored the Europeans. One by one, other Europeans began trading with China. Since the flag follows trade and missionaries follow the flag it only followed that the trading nations had to send warships to protect their businessmen and their missionaries. The missionaries descended on China in droves. Most settled in the Yangtze Basin. The Treaty of Wangsia guaranteed certain rights to the United States and her citizens in China. It was signed in 1844 and was followed 14 years later by the Treaty of Tientsin which gave the United States the right to navigate China's rivers and to call at the treaty ports of Chinkiang, Nanking, Wuhu, Kiukiang, Hankow, Shasi ,Changsha, Ichang and Chungking. To ensure the timely delivery of mail to and from China for its citizens and other foreigners, the US Postal Agency was opened in Shanghai in 1867 for the benefit of US those who did not wish to entrust their correspondence to the vagaries of the Imperial Chinese Postal Service. The Agency was placed under the US Consul in Shanghai who was authorized to sell US postage stamps at face value for gold or US currency. In 1919 the US Post Office Department opened offices in China and sold overprinted US postage which was valid for mail to addresses in the US. In 1922, all foreign post offices in China were closed ending an interesting philatelic era in that land when the US, Great Britain, France, Germany, Italy, Japan and Russia operated post offices or postal agencies in China. Coincidentally, they were the same countries that enjoyed the rights of extra-territoriality and ran gunboats on China's rivers. See figures 1 through 4 which illustrate the convoluted routing mail took to get to the sailors in China. The US maintained a coaling station and a naval hospital in Yokohama in the wake of the "opening" of Japan to the west in 1854. The first US ships to receive their own on-board post offices got them in 1908. From that point on, mail from US warships and auxiliaries was cancelled on-board and not ashore. Four years before the Treaty of Tientsin went into effect, on May 24, 1854, USS SUSQUEHANNA (Captain Franklin Buchanan) a 2500-ton fully rigged steam frigate escorted by the tug CONFUCIUS steamed up the Yangtze River from Shanghai to Wuhu to show the flag and survey the river. If the Chinese were offended by the appearance of the warship and her escort they made an issue of not making an issue of it. The USS SUSQUEHANNA returned to Shanghai on June 6, 1854. For all intents and purposes the United States Navy had just inaugurated the Yangtze Patrol. It would last 13 years less than a full century. Two Civil Wars A World Apart And Their Aftermath At the crack of dawn on May 1, 1861, Commodore Cornelius K. Stribling, the acting US Minister to China and newly-appointed commander of the US Navy's East India Squadron took a trio of warships consisting of USS HARTFORD, a 2900-ton screw sloop, USS SAGINAW, a 453-ton side-wheeler, and USS DACOTAH, (Figure 1) a newly commissioned steam sloop, up the Yangtze. Despite all these titles and burdens of office he was blissfully unaware that the Civil War had started back home on April 12th. That singular event's repercussions would be felt as far away as China before it was over. Stribling's squadron penetrated as far as Yochow and made a slight penetration into Tungting Lake before heading back to Shanghai. Stribling's small force had shown the flag further up the Yangtze than any other US Navy ship to date.

USS DACOTAH, Figure 1 With the start of the Civil War, the US Navy recalled all its warships from Asia. By 1862, the USS WYOMING, a 1400-ton screw sloop was the only US warship left on the Yangtze. In Hong Kong 17 American merchantmen lay idle for want of US-bound cargo. China too was about to dissolve into one of its many civil wars. This one was called the Taiping Rebellion and it would last for 10 years and account for 20 million Chinese dead. It did not touch American lives but it did bring traffic on the Yangtze to a near standstill. In 1866 with the Civil War in the United States ended, the Navy felt it prudent to give poor WYOMING some company.So it sent: USS WACHUSETT, a 1500 ton screw sloop

Figure 2, USS MONOCACY The first post-Civil War naval excursion up the Yangtze by the Navy took place in August of 1866 when the USS WACHUSETT (CDR Townsend) ascended the Yangtze and made port calls at Chinkiang and Hankow. The heat was unusually bad that summer and CDR Townsend died of heatstroke on the trip. In February of the following year, with a heartier skipper, CDR R. W. Schufeldt in command, she re-visited the prior year's ports and CDR Schufeldt was amazed to discover how many American flag vessels there were on the river. As a matter of fact more freight travelled on the Yangtze in American bottoms than on any other making the case for more US gunboats to protect them stronger. In November of 1870, the USS ALASKA (CDR Blake) a 2400-ton screw sloop, became the largest US Navy vessel to reach Hankow. The Three Gorges In June of 1870, 22 Europeans, including 10 Catholic nuns were massacred in Tientsin. USS ASHUELOT (CDR Edmund Matthews) was dispatched there to safeguard American and European lives. She remained there "on station" until the river's rising water level permitted her to leave in April of the following year. For the next three years she steamed in Asiatic waters. And then in 1874, with CDR Matthews still her captain, she was ordered up the Yangtze again to keep an eye on things and be generally useful to American businessmen and government officials. She found Chinkiang a welcome stop. The missionaries were busy proselytizing and the businessmen were making money.After provisioning from the British firms of Middleton & Company and Jack Ayong & Company she hosed off her anchor and made for Nanking, a foreign "settlement" and China's Southern Capital. Here the tsung-tu or Governor-General of the provinces of Kiangsu, Kiangsi and Anhwei received CDR Matthews with all the pomp and ceremony at his command. His official duties properly disposed of, Matthews steamed up to Kiukiang where the local tao-tai snubbed him. Matthews pushed on to Hankow where Great Britain, Russia, France, Germany and Japan had "concessions". In Hankow, the brother of the Guardian of the Throne gave CDR Matthews a friendly "heads up" advising him to beware "rudeness" to foreigners. After surviving an evening being entertained by a very happy group of Russians ashore, CDR Matthews pushed on upriver, crossed Tungting Lake and re-entered the Yangtze River. Reaching Ichang, 975 miles above Shanghai, USS ASHUELOT had bested Commodore Stribling's former record. But she could go no further because of the rapids in the Three Gorges that stretched from Ichang to Fengjie. At Ichang, CDR Matthews and a survey party from the ship decided to survey the Three Gorges and their rapids. For eight days they did so on foot. They saw the Xiling, the Wu and the Qutang Gorges and decided that these Three Gorges, 192 kilometers in length, were impassable to the steamers then in use on the river because of the treacherous currents and rapids with their snags and shifting banks. Any ship attempting to ascend the Three Gorges would need a steady source of power and great manueverability. No ship on the Yangtze at that time had these qualities. CDR Matthews returned to Shanghai on July 21st and made his report. On April 30, 1879, USS ASHUELOT was chosen to take former President Ulysses Grant and his party on board at Hong Kong and deliver them anywhere they wanted to go. The former president and his party were on a two-year tour of the world. From October of 1879 until the spring of 1880 she underwent an extensive yard period to repair 17 years of assorted wear and tear. The yard made her serviceable again and she continued to steam in Asian waters for the next three years. She met her end on February 18, 1883. While steaming through a heavy morning fog, she struck some rocks off East Lamock Island killing eleven of her crew. Damaged beyond repair, she was abandoned. Enter USS PALOS And USS BENICIA In January of 1871 a most curious addition arrived for service on the Yangtze. It was the USS PALOS, a 420 ton screw tug that had the dubious distinction of being the first vessel of the US Navy to transit the newly built Suez Canal (Figure 3). It was apparent from the start that she was a misfit. RADM T.A. Jenkins, soon- to- be Commander of the Asiatic Fleet, reported disdainfully that she was slow, a prodigous coal burner, maneuvered sluggishly and had a deep draft preventing her from going places on the Yangtze that a proper gunboat could get to in an emergency. This PALOS was the first of two vessels to bear that name. She was just another of the "misfits" that the US Navy relegated to the Asiatic Station.

Figure 3, Suez Canal Also in 1871, USS BENICIA made a visit to every Yangtz River port she could reach and found that each one had a Royal Navy gunboat based there and only a Royal Navy gunboat. The Royal Navy used the station ship system. The US Navy did not. It simply did not have enough gunboats to station one in every treaty port. Instead the gunboats of the US Navy were on constant roving patrol. That practice burned up huge amounts of coal and proved wearing on the machinery which was old and worn before the boat ever got to the Yangtze. USS BENICIA spent just two years on the Asiatic station during which time the 2400-ton screw sloop participated in Admiral John Rodgers's Korean intervention in May and June of 1871. She then became part of the North Pacific Squadron; carried King Kalakana of Hawaii to San Francisco; and decommissioned at Mare Island in 1875. She was sold 9 years later. Where other nations made a great show of their Asiatic warships, the US had little use for impressing the natives since we had a smaller presence there than the other nations, and after all, we were not a colonial power. While other navies were bustling about impressing the natives and "showing the flag" our Yangtze gunboats were few and far between and their crews were hard-pressed to keep them afloat due to the fact that they were at the end of a very long supply line and there were other priorities, namely the Atlantic and Pacific fleets, never mind the "misfits" and Civil War castoffs of the Asiatic Fleet. The prevailing philosophy in Washington seemed to be this: "If we can't use it anywhere else, send it to China They'll be glad to get it."

But China was sweet duty for the gunboat sailors and officers on the Yangtze from the very beginning. The duty became sweeter with the passage of time. It was different for sailors and officers in the Asiatic Fleet , the "Outside Navy" as the gunboat sailors called it. The initial tour in the Asiatic Fleet was for 30 months. If a sailor liked it, he shipped over. Some sailors spent their entire careers in Asia. Those who served on the Yangtze gunboats were on their own and it showed. The officers were a different breed entirely. Annapolis did not train them for this arduous duty. They grew into it and became experts at applying just the right measure of leadership, diplomacy and raw courage as each situation demanded. There were no recorded cases of mis-applied force. There were no "gunslingers" on the Yangtze. Whenever force was applied it was applied reluctantly and was focused and effective. These were a hard, tough, resourceful breed of professionals who served their country proudly and very often at great cost. Life on the Yangtze had its compensations for officers and sailors alike. When a Yangtze gunboat sailor woke up he was greeted by one of the several coolies who lived aboard. His bunk was immediately made up and a cup of steaming coffee was thrust in his face. If the bunk needed fresh sheets they were there in an instant. If the sailor slept in a hammock, it was immediately bundled and stowed.The coolies made sure that the sailors always had clean, freshly pressed uniforms, shined shoes, and clean web equipment Breakfast was a feast of pancakes, eggs, sausage, bacon, cereal and whatever else the crew could think of to ask the coolie messcook. Milk was often available, so were fresh fruits and vegetables. Coolies washed the dishes, swabbed the deck after each meal and set the tables for the next meal. The work was done quickly and efficiently and all for the princely sum of US$5.00 per month or the same amount in Mexican silver dollars if the sailors were paid in that currency which was coin of the realm in China for the sailors. Need a shave or a haircut for inspection or a heavy date ashore? The barber coolie was there in a flash. The gunboat coolies augmented their $5.00 monthly stipend with "squeeze" which can best be described as payment for services rendered like haircuts, shaves, shoeshines, etc. "Squeeze" was billed monthly and collected promptly on payday from the sailors. There was a certain synergism in this arrangement. The sailors learned to depend on the coolies and the coolies lived off the sailors. Nothing was wasted. Even the garbage, broken tools, and worn out uniforms became mediums of exchange. The gunboat coolies were the princes of the Yangtze. They exchanged the boat's castoffs including its garbage to the bumboat coolies who were always present alongside. These "entrepreneurs" took the castoffs and sold them ashore. In return for the gunboat coolies' largesse the bumboat coolies scrubbed the sides of the gunboats after coaling ship, until they shone. Appearances counted for everything in China. The gunboat coolies wore the sailors' castoff uniforms, cut down to size and expertly mended. One had to look closely at the crew of a US gunboat in those days to tell the sailors from the coolies. The Chinese bumboat coolies lived like their brothers ashore at a subsistence level if they were fortunate. The gunboat coolies lived like princes aboard. They ate what the crew ate, lived aboard in comparative luxury and were clothed in what for them was luxurious attire. If one got sick or was injured in the course of his duties, the Pharmacist's Mate, if there was one aboard, looked after him. When a coolie died or was retired forcibly by sickness or old age, his position aboard the gunboat was inherited by his son or a close relative. The gunboat coolies did the dirty work that the sailors in the "Outside Fleet" did. They coaled ship, scrubbed decks, polished brightwork, scraped and painted, tended the boilers, maintained the engines, boilers and pumps (always under the watchful eyes of the sailors) and made themselves useful. The sailors stood watches, handled the machinery and supervised the coolies. The coolies for their part took advantage of this rare opportunity and learned by watching. If a coolie, once in a while, stood an engine room watch underway without blowing up the boat, who was the wiser? Topside, it was another story. There were always officers watching so the deck coolies usually stayed out of sight except when their duties called them there. It was a feudal system in a feudal land and it worked to everyone's satisfaction. Sailors were not permitted ashore unless they were in uniform and no "respectable" restaurant or hotel in a treaty port allowed sailors in.The native Chinese establishments were not that fussy. Officers were allowed ashore in civilian clothes and were welcomed everywhere especially if they were bachelors. Sailors lived on the equivalent of US$21.00 per month, chiefs and rated sailors earned more. Pay was in Mexican silver dollars and later in $20 gold pieces. Ashore each gunboat's crew staked out its own bar with attached.bordello and woe betide the sailor of another crew who trespassed. The girls, called "pigs" in that politically incorrect time, serviced their clients with pleasure and an eye to marrying a retired chief and settling down on a pension that dwarfed the pay of a Chinese general. Some did marry a retired chief and did settle down to a domestic life of what passed for shameless luxury. Gunboat sailors prided themselves as a breed apart and their uniforms showed it. They were issued a size or two too large on purpose. When the sailor got his uniform he took it to one of the custom tailors ashore or to one of his own gunboat's coolies who doubled as a tailor. The uniform was tailored to fit like a second skin. The sleeve cuffs had elaborate fire-breathing dragons embroidered into them in vivid golds, greens, yellows and reds. With his sleeves rolled back and the dragons breathing fire from both his wrists, he announced to the world who he was. The real Navy might have looked down on the gunboat sailors, but they dressed and acted like lords. If theYangtze gunboat sailor lived like a lord, then his officers lived like kings. There was, in those long gone days, a gulf between officer and sailor that neither dared to bridge. But appearances were deceptive. The casual observer on a Yangtze River gunboat of the US Navy would be hard pressed to distinguish sailor from officer and both from the coolies. All wore undress whites on duty without any indications of rank and all wore the same sailor hat. Facial hair was permitted and worn in many styles by officer and sailor alike. The only distinguishing mark that separated one from the other was the shoes they wore. Officers wore white shoes and sailors wore black. If the Washington brass relegated an officer to the China Station, his career, like that of a losing manager of a professional baseball team, was in jeopardy and he had better turn in a series of exemplary efficiency reports so he could get his career back on track. There were offsets and compensations to soften the bump in the road. For one thing, if you were a married officer your wife and family could join you in Shanghai where housing was cheap; battalions of servants available, willing, and inexpensive. Food and drink were plentiful and readily available. There were acres of markets where every conceivable exotic food was sold. A case of Gordon's Gin liters was available for just US$3.00. Junior officers usually banded together in groups of two or three and rented a large house or apartment complete with servants. Membership in all the "right" social clubs was made available to the officers. Custom tailors abounded and the finest cloth imported from England, France and Italy was miraculously transformed into tuxedos, dress uniforms, and suits that rivaled any Saville Row creation. Doldrums Following the signing of the Chefoo Convention in 1876 few US gunboats steamed up the Yangtze, perhaps only one a year. As ususal, the gunboats were either worn out Civil War veterans or misfits of some other stripe that no one wanted. But as poorly chosen as they were for the duty thrust upon them they did impress the bandits, warlords and assorted Chinese officials they encountered. One such gunboat was the USS SWATARA, (Figure 4) a river-going fortress. Armed with a wide assortment of weaponry she was looked upon with awe by the Chinese. She carried 15 officers, 174 sailors, and 26 Marines. The Marines manned the single 8-inch smooth bore, and the 60-pounder, the six 9-inch naval rifles, two 20-pounders and a single 12-pounder. And if that was not enough, she boasted a 3-inch howitzer for plunging fire and a Gatling gun.

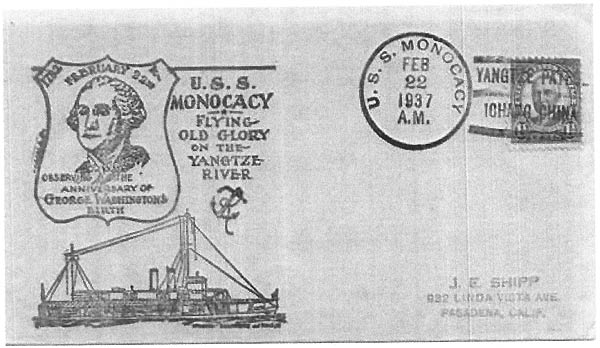

Figure 4, USS SWATARA "Two Side Walkee" and the River Dragons Because of her two side-wheels the locals dubbed her "two side walkee". Officially she was the USS MONOCACY, the first of two gunboats to bear that name proudly on the Yangtze, and typical of the type of boat sent to the Yangtze to look after American interests. One fine morning in 1877, with her side wheels churning the river at a stately 12 revolutions per minute, and a full head of steam (20 pounds psi.) testing her seafeties, she let go her lines from her buoy at Shanghai's Whangpoo River and headed downstream to join the Yangtze, 13 miles distant. Her skipper, CDR Joseph P. Fyffe was on the bridge, and she obediently fell in with the river traffic heading upstream .His orders were to establish the first US Consulate at Ichang, 975 miles upstream. That first night, the MONOCACY anchored off Nanking. While the crew slept unawares the tide came in slowly and turned her around on her hook so that instead of facing upstream , she now faced downstream. The next morning, before first light, her Executive Officer started her moving. As it became light he saw a city looming in front of him and MONOCACY was heading straight for it. Realizing what had happened he got a grip on himself and managed to turn her back upstream before CDR Fyffe, who had just come on the bridge, caught on. It was just another trick the river dragons were to play on unsuspecting gunboat sailors. If CDR Fyffe learned later what had almost happened, he never mentioned it. USS PALOS, the unwanted stepchild of the Yangtze Patrol, had finally outlived her usefulness. She was sold at auction in Nagasaki, Japan in January, 1893 for 7000 gold yen, the US equivalent of $3500. Her namesake, the second USS PALOS (PG-16) would be better suited to the task. The obvious short comings of the US gunboats was becoming more of an embarassment to the Navy. The Royal Navy designed their gunboats specifically for the Yangtze while the US Navy sent misfits and relics to do a job that was becoming increasingly more difficult. In 1893 the talk in Washington was about a gunboat designed exclusively for river patrolling on the Yangtze. The first two of the boats were the USS HELENA (PG-9)(Figure 5), and USS WILMINGTON (PG-8). Both were commissioned in 1897. WILMINGTON arrived in China in 1901 and spent the next 22 years in Asia, leaving in 1923 to become a training ship on the Great Lakes. She even served as an escort in WWII as the USS DOVER (IX-30) and at war's end she was struck from the Register of Naval Vessels in 1946 and sold for scrap that same year at age 50. Something of a record.

Figure 5, USS HELENA HELENA arrived in Asia six months before WILMINGTON and spent her entire career in Asian waters with only a brief tour on the Yangtze River. She was decommissioned on May 27, 1932 and sold on July 7, 1934. By 1896 the US had 18,000 tons of warships on the Yangtze; the Royal Navy, not to be done by the upstart Americans, had 59,000 tons; the Czar's gunboats weighed in at about the same as the Royal Navy; France had 28,000 tons and Germany had 23,000 tons. Gallic Finesse The French gunboat OLRY steamed up the Yangtze River, to Suifu, and planted the tricolor over a complex of mission buildings "owned" by some French missionaries. Suifu (Iping) was not a treaty port. Non-treaty ports forbade foreigners from buying land there. All foreigners that is, except missionaries. The missionaries signed over their land to the French government and stayed on anyway. The French built barracks, mess halls, an arsenal, a parade ground, storage facilities. In short, a small naval base. The Chinese looked the other way and everyone got what they wanted. The French got a military outpost where none had been permitted and the Chinese saved plenty of "face".The French even planted a vineyard. "After all, mon ami, one must take one's pleasures where one can, mais non?" The French did a magnificent job of charting the Yangtze. The resulting charts were the first really good ones ever made of the Yangtze and were used by everyone, even the Chinese themselves. A French naval officer named Audemard went up the Yangtze with a survey party, surveyed the Three Gorges and with inpenetrable Gallic certitude concluded that no steamers could ever negotiate the 410 rapids in the Three Gorges. Spoils of War RADM George C. Remey, C-in-C Asiatic Fleet had no reason to feel secure in 1900, the last year of the 19th Century. He had his flagship, the venerable USS BROOKLYN (ACR-3) and 24 gunboats, all but six of them taken from the Spanish after the Spanish-American War just concluded 2 years before. Earmarked for the Yangtze were this assortment of ten combatants and non-combatants: USS ELCANO (PG-38) (Figure 6) But this fleet was severly limited by age and condition. The gunboats inherited from the Spanish were first used to chase insurrectos up and down the rivers of the Philippines. With the insurrecto leader Aguinaldo finally defeated by 1901, RADM Remey could pay closer attention to the Yangtze Patrol and the South China Patrol. It would be two years before the ex-Spanish gunboats would arrive on, the Yangtze. When USS ELCANO, USS VILLALOBOS and USS POMPEY arrived in Shanghai they were immediately placed under the operational control of the skipper of the monitor USS MONADNOCK, a venerable 4,000 ton Civil War relic that had been retrofitted and modernized so many times little remained of her original self. During the winter of 1902/1903 she served as station ship in Shanghai.

Figure 6, USS ELCANO POMPEY, originally a collier, later a torpedo boat tender, never became operational due to the chronic shortage of crewmen and her general state of advanced decrepitude.. PAMPANGA was sent to the South China Patrol and did not serve on the Yangtze. She was decommissioned on November 6, 1928 and sunk by naval gunfire by ASHEVILLE and SACRAMENTO. CALLAO served on the China coast and on the Yangtze until she decommissioned on January 31, 1916. Recommissioned, she was designated YFB-11 in June of 1921 and served out her days as a ferryboat for the 16th Naval District. On September 13, 1923 she was sold in Manila. GENERAL ALAVA, an auxiliary, spent most of her time in the Philippines. Then she was moved to Shanghai and became that port's receiving ship for a short period before serving very briefly on the Yangtze Patrol. She decommissioned on June 28, 1929. MONTEREY received new boilers in Hong Kong and served as the station ship in Shanghai. She completed a diplomatic mission to Nanking in 1902 and was sold. QUIROS served on the Yangtze until she was decommissioned and sunk by naval gunfire on October 16, 1923. All that spring and summer of 1903, USS VILLALOBOS and USS ELCANO went looking for trouble on the less often travelled reaches of the Yangtze like Lake Poyang. Their presence in those parts ruffled Chinese feathers and led to a spirited and acrimonious exchange of diplomatic notes between Chinese government officials and American diplomats. But nothing came of these notes and the patrols continued.

Figure 7, USS VILLALOBOS As the gunboat men became acclimated to the river and its dragons, they fell in with its timeless rhythms as they moved effortlessly upstream and down. During the spring and summer when the melting snows were replaced by the monsoon rains and the river ran at its maximum depth, they ventured far upstream and in the fall and winter when it was a low water they patrolled the middle and lower reaches of the river where the water was deep enough to prevent the embarrassment of grounding. Should one of them become stranded in the river because of low water, the crew could look forward to a winter of boredom afloat and ashore, tied to a pontoon somewhere on the Yangtze or on one of its tributaries and playing pinochle, cribbage and Acey-deucy until the cards disintegrated and the click of the dice began to grate on the men's nerves.

Figure 8, USS QUIROS The river dragons protected the sailors from the outside world and enveloped them in a cocoon where time stood still. And although enlistments expired and orders called others far away, China had cast her spell on all those who had served in her. If you should ever meet a Yangtze gunboat sailor, ask him about China and watch closely as he becomes transfixed as though a spell had been cast on him. He will speak of river dragons, evil spirits and chatter endlessly about the Chinese who are a mysterious race, inscrutable and pragmatic at once. He will tell you improbable stories about the Orient, some true, most the figment of his imagination or the imagination of others and as he waxes more and more eloquent, you will come to the realization that somehow, China had changed him permanently. Some sailors came, became enchanted and spent their entire careers there. Many retired there, married and stayed to open a small business to supplement their pension..

Figure 9, USS MONTEREY Officers too, came and went and so did the C-in-C's of the Asiatic Fleet. Commodore Edmund P. Kennedy was the first C-in-C Far East in 1835 and Admiral Thomas C. hart was the last. Some of the men who filled that billet were memorable likeMatthew C. Perry, Joseph Tattnall, George Belknap, George Dewey and the three named Rodgers, John, Frederick and William L. While the Yangtze Patrol went about its business, events in Europe were proceeding apace. Sabres were rattling and ultimatums were flying like snowflakes in a blizzard. Rhetoric was heating, headlines screaming and temper were fraying. Events would soon overwhelm Europe and take down entire dynasties, change borders between countries and create entirely new ones out of old ones. The Europe of 1919 would not resemble the Europe of 1914.

Figure 10, USS MONADNOCK "Pathos" and "Monotony" While Europe was unravelling, there appeared on the Yangtze River a pair of gunboats designed for the express purpose of negotiating the rapids of the Three Gorges and entering the heretofore unreachable Upper River, that part beyond Ichang. These two were the second USS MONOCACY (PG-20)(Figure 11) and the second USS PALOS (PG-16) (Figure 12). In due course they became : "Pathos" and "Monotony". They were 200 ton- sister ships capable of 13 knots. Both carried about 50 men in the crew. Both were built at the US Navy's Mare Island shipyard from plans based on the Royal Navy's Yangtze gunboat HMS WIDGEON. The sisters were then dis-assembled and shipped to Shanghai where they were re-assembled in 1914 at the British-run Kiangnan Dockyard. MONOCACY was launched on April 27, 1914 and PALOS followed a few days later. MONOCACY was on her way just a few days after launching, destination: Kiating (Lo-Shan) a city on the Min River, one of the Yangtze's main tributaries. It was 1700 miles from Shanghai and at the very limit for steam navigation. MONOCACY and sister ship PALOS became the first US steam driven warships to ascend the rapids in the Three Gorges in 1914.

Figure 11, USS MONOCACY

Figure 12, USS PALOS Bedfellows Make For Strange Allies When the Great War came in August of 1914, the European powers recalled their warships from China. Even the little tin gunboats went home. The US Navy was left alone on the Yangtze. She was the Navy of a neutral nation in a neutral country. But that was about to change. In April of 1916, MONOCACY was at Chungking, sister ship PALOS was on Tungting Lake, VILLALOBOS was at Hankow, SAMAR was at Kiukiang, QUIROS was at Nanking and HELENA (PG-9), GALVESTON (C-17) and CINCINNATI (C-7) were at Shanghai while poor, restless WILMINGTON was on roving patrol. "Anyone Here Seen My Breechblock?" War came to the United States on April 6, 1917. The Navy's ships in China became the vessels of a belligerent nation in a neutral country. Lieutenant H. Delano, skipper of MONOCACY ordered the gunboats to Shanghai where they were to be interned according to international law. The captains of the gunboats surrendered their breechblocks to the US Consul and they and their crews were duly interned. For the next four months the American sailors sat around and griped, chipped rust, painted, polished brightwork, while their officers made work for them. Morale sank, disciplinary problems flourished and malingering became a high art. The Bund in Shanghai was almost deserted. Foreign businesses slimmed down to skeleton crews, droves of foreigners went home to do their part in their country's war effort. Spies of all nations were as common on Shanghai's streets as they would be a generation later on the streets of Lisbon and in Switzerland's main cities. China's land and resources had long been coveted by Japan. China's rulers, the Manchus, were weak and their weakness only encouraged Japan's ambitions. The Boxer Rebellion of 1900 had sparked a nationalist fervor in the country that only grew with time. Japan saw her chance approaching. But it was China who acted first. She declared war on the Central Powers on August 14, 1917. She felt if she came in on the side of the Allies they would defend her after the war from Japan's designs. She was wrong. On August 16, 1917 the American sailors were released from internment and their breech blocks were restored. China and the United States were now allied against the Central Powers. On the morning of January 17, 1918, while the war in Europe was raging, MONOCACY was plodding up the Yangtze, fifty miles above Chenglin. It was low water and the sailors were taking soundings carefully. It was a long, perilous trip with the river's channel narrowing dangerously. Reports of Chinese soldiers firing on foreign vessels had been received and bags of coal were piled on the main deck to afford some protection to the sailors. She flew the biggest US flag she had for all to see. Suddenly, a rifle shot hit her jackstaff and seconds later a stuttering volley erupted from both banks. Chief Yeoman Harold LeRoy O'Brien fell, mortally wounded. She was the duck in a shooting gallery that stretched for two miles along a stretch of the river too narrow for her to turn in. The next best thing was to shoot back. After a half dozen rounds of HE from her 6-pounder the firing ceased and the shooters fled into the mountains. MONOCACY found a wide spot in the river and reversed course. Vigorous protests flowed from Shanghai to Peking, each answered by the obligatory "so sorry". Finally China ponied up US$25,000 for Chief O'Brien's widow. And the case was closed. But it would be the opening scene in a play that would unfold over the next couple of decades as China fought for her very survival against incredible odds. The play, of course, was a tragedy. For centuries the Yangtze was the 'ex officio' boundary between north and south China. The grain-eating north and the rice-eating south were natural rivals and the Yangtze was the venue of contention. Gunboat availability iimproved. On the Upper River, from Ichang to the headwaters, two US gunboats MONOCACY and PALOS patrolled tirelessly. The Royal Navy had 15 gunboats on the same stretch of the river. It was a curious imbalance. Despite repeated pleading by C-in-C Asiatic Fleet, no new boats were in the offing for the Yangtze. Congress was in a cost cutting mood and the Navy was fighting for every penny. On Christmas Day, 1919, Washington threw the Asiatic Fleet a bone. Although theYangtze Patrol had existed ex officio since 1903, and had been known as the Second Squadron of the Asiatic Fleet. It was no longer a bastard command; it now had a name that reflected its responsibilities: Yangtze Patrol and a father: a four striper, Captain A.T. Kearney. It was small bone but it was a start. YangPat was now a real command, and its skipper was ComYangPat. It was about to suffer its first casualty. On June 30, 1920, SAMAR collided head on with an oil tanker. The 33-year-old gunboat, full of years and bad machinery was adjudged too badly damaged to be repaired. She was stricken from the Register of Naval Vessels after being decommissioned on September 6, 1920. She was sold the following year. "Pathos" And "Monotony" Redux Six-year-old MONOCACY was feeling rather poorly. After a survey, she was fould to be suffering from a variety of maladies that included but were not limited to boilers that could not maintain a full head of steam if her engines ran at full throttle for more than three minutes. And that was just the beginning. The clearances between pistons and cylinder walls was often as wide as three-thirtyseconds of an inch, her ice machine was broken, her radio was inoperable, her main engine had leaky valves, one of her two air pumps had a leaking piston and the other had a broken valve rod, the steering engine had a broken piston ring, her port circulating pump also suffered from a broken piston ring, her forward main feed pump had a broken valve rod. The report ended on a positive note: her crew was said to be in good spirits. PALOS' crew was also in excellent spirits. She finally broken free of the ice that had imprisoned her all winter and she was steaming at full speed for Shanghai and all its sinful pleasures. If she carried oars and sails the crew would have rowed like madmen to get to the "Paris of Asia" all the faster. With several months' worth of "Mex", the Mexican silver dollars Uncle Sam used to pay his Yangtze gunboat sailors sagging in their dress whites, the sailors were looking to slake all kinds of thirsts. Downstream awaited every vice known to man and some new ones the Chinese invented. Visions of comely maidens named Jade, Orange Blossom, Lotus Flower, and Golden Petal dancing behind their fevered brows, the sailors washed, groomed and combed themselves into exhaustion. Freshly pressed uniforms were laid out, shoes spit shined to patent leather perfection,their hair cut and beards shaved, after shave lotion and hair oil applied, all in readiness. But they never made it. A malignant fate turned them back upriver and ordered them to clear the river and its banks of pirates, war lords, bandits and those of that ilk who preyed on innocent businessmen and missionaries.Especially missionaries. PALOS made for Sao Ta Chia, a tiny village where bandits were holding a wood oil junk for ransom. In no mood to negotiate, PALOS's skipper, LT George S. Gillespie ordered her gunners to let loose with a few rounds of HE from her six-pounder. The shells exploded harmlessly against a hillside but the "kidnappers" got the message and disappeared. The junk was saved. Often, that was all it took to resolve a problem. At Wanhsien, PALOS next encountered a US flag passenger liner, the SS ROBERT DOLLAR of the Dollar Line. The liner had a Chinese General aboard with 100 of his troops. They were holding the liner's captain and his passengers for ransom. This was an exercise in diplomacy that now faced LT Gillespie. He realized he was outgunned and that one false move could mean death for all. Gillespie somehow managed to sweet-talk the General and his men into leaving peacefully. It was one of those crazy moments on the Yangtze that cropped up all to often and contributed to the myth of Chinese inscrutability, helped along by the river's dragons who loved jokes. There was not one gunboat captain that did not have a similar tale to tell. Facing down pirates, bandits and warlords was all in a day's work Of Samovars, Blinis,and Chicken Kiev With the collapse of the White Russian counter-revolution in Russia, thousands of Russians fled the country with their families. Many had been soldiers in the White Army. When Japan withdrew its troops from Siberia in 1922 the White Russians sheltering there from the Communists had nowhere to go. Twenty-nine Russian and two Japanese ships evacuated 11,000 White Russians and their families from Vladivostok and took them first to Possiet Bay in Japan and then to Korea. From Korea they went to China. They arrived stateless, penniless and in sore need of hope. A few years later one would think Shanghai had become a Russian outpost. Signs in Cyrillic festooned the shops of Avenue Joffre in the heart of the Russian settlement. The sights and sounds of the Mother Country had somehow been transported to this corner of China. The emigres sang the old songs, played the old tunes and ate the food they had been nourished on since childhood. They also plotted and schemed to win back their former homeland while drowning their sorrows in gallons of vodka and when the melancholy overwhelmed them they sought comfort in steaming glasses of tea. It was just like the old country, too much like it as a matter of fact. The Chinese Communist Party was born in Shanghai in 1921. Being newcomers they took whatever employment they could find. It was always menial, poorly-paying and below their former station in life. Their women were more successful than the men. Their daughters replaced the Chinese women who had been favored by the sailors. Now it was Vera, Irina, and Natasha, who worked the bars, dance halls, massage parlors and brothels. The Russians were educated, well-mannered, and willing to please all comers. The sailors loved the change. They were in a sort of heaven. The times were changing for the Navy too. ADM Joseph Strauss was now C-in-C Asiatic Fleet and flew his flag in USS WILMINGTON. and ComYangPat was a four-striper, Captain D.M. Wood who flew his flag in USS NEW ORLEANS (CL-22, ex PG-34)a small cruiser. Enter Admiral Bullard After years of constant lobbying, an officer of flag rank was named ComYangPat. He was RADM W.H.G. Bullard who succeeded Captain Wood. Bullard arrived on October 12, 1921 and shifted his flag to tiny, 900 ton USS ISABEL, known forever afterward as the Admiral's yacht. HQ of the Yangtze Patrol was moved from Shanghai to Hankow lock, stock and barrel. At Hankow, a warehouse called a godown was rented and it grew to contain every conceivable item to keep the Yangtze Patrol alive and functioning, and its sailors clothed, fed, and kept safe from venereal disease. It even maintained a supply of coffins if a sailor ran into bad joss. At Chungking, the Standard Oil Company's supply of petroleum products was running low because re-supply ships could not operate safely due to bandits, renegade generals and warlords. The usual mix of bad guys looking to make a fast buck or, more precisely, apply "squeeze" to the foreign devils.The local Standard Oil manager appealed for help in the form of armed guards from MONOCACY's skipper LCDR G.E. Brandt. Brandt was happy to oblige. Standard Oil was an American company, the petroleum products so sorely needed were property of Standard Oil. The manager offered to reimburse the navy for the time and effort of the MONOCACY's sailors. Brandt organized a convoy of sorts. It consisted of two houseboats, each manned by three heavily- armed-to-the-teeth sailors and a chief. Each houseboat escorted three large junks loaded with petroleum product. The voyage from Standard Oil's tank farm to Chungking involved negotiating the rapids in the Three Gorges safely. The voyage began in May of 1921 with the eight vessels moving slowly up the river which was at high water. Each night, before securing to the bank, the sailors would unleash a furious fusilade of automatic weapons fire punctuated by tracers into the surrounding hillsides to frighten away any bandits whose heads were filled with larcenous dreams. At first light the convoy started upriver again with the aid of hundreds of naked coolies pulling on towropes bent double from their exertions. Slowly they climbed the rapids and finally reached Chungking with its precious cargo. The system worked, Chungking's lamps were filled with kerosene and Standard Oil's stockholders were happy. River traffic from Shanghai had been creeping steadily up the Yangtze.ever since tiny, underpowered Leechuan, a steam launch safely negotiated the rapids of the Three Gorges in 1898. By 1923, Chungking's anchorage, Lungmenhao Lagoon was crowded with ocean going steamers. Ships of the UK-flagged China Navigation Company, the Indochina Steam Navigation Company, the US-flagged Dollar Line, the Cox Shipping Line, the Asiatic Petroleum Company, the Standard Oil Company and others too numerous to mention arrived and departed regularly. Yet for all this traffic, Chungking prospered while the surrounding countryside was aflame with war and the river a home for audacious pirates. Rival warlords, Chinese Communist troops, Nationalist soldiers and gangs of bandits all fought one another with regularity. Roving pirate bands flourished on the rivers of China. Steamship traffic attracted those with enough men and arms to dare a highjacking because the rewards were enormous. The little tin gunboats were hard pressed to keep the steamers safe from these predators. Mostly they succeeded, Their job demanded nerves of steel, guts, a gambler's instincts and no small measure of diplomacy and patience. The skippers of the gunboats steaming on the Yangtze in those days had those qualities in spades. Christmas 1923. In the USA the Jazz Age was in full swing, prosperity was everywhere, two chickens were roasting in every pot, there was a car in every garage, Al Capone owned Chicago and the "Flapper" was every girl's role model. Congress was performing major amputations on the defense budget. In China, PALOS was in Chungking barely afloat in 5 feet of water. Just that previous summer the water level at Chungking was 49 feet, down from 100 feet that spring when the snows melted. It was Christmas after all and the river dragons were giving everyone a well deserved rest from their antics. It was Christmas and Christmas in China meant party time for the foreigners forced to spend it in a foreign land. Invitations flew through the air like snowflakes. The bankers, the businessmen and the diplomats outdid each other in conviviality and hospitality. The red carpets were rolled out, crystal chandeliers were aglow, wine cellars were depleted, decorations were everywhere. It was time to party. Prosperity was contagious. The USA was awash in it and Europe, truncated, disembowled and recast was enjoying prosperity too. So.. let the good times roll. And as the champagne flutes chimed and 1923 slipped into the record books, the infant year, 1924 arrived, full of hope and dreams of wealth. But the river dragons had fathered 1924. The Year Of The Junkmen And The River Dragons It began with a spate of incidents precipitated by the guild of junkmen. They banded together to negotiate uniform wages and freight rates from the shippers. The shippers stood fast. The junkmen were adamant. No one budged. Then the incidents began. The junkmen called on the river spirits to assail "the foreign devils". Whether their anger was rooted in economic reasons or plain, old fashioned nationalism, no one knew. Perhaps it was both. Mid May, 1924 was a banner year for groundings in the Three Gorges. First to run aground was the American Yangtze Rapid Steamship Company's brand new SS Chai Ping. For reasons known only to himself, her pilot deliberately steered her into a huge rock. She began to sink by the bow and her skipper ordered her beached to save her.On April 24th, the SS Robert Dollar was wrecked and then in quick succession so were three British ships. Further upstream the SS Alice Dollar's hull was holed but her crew managed to save her by some adroit damage control. The shippers caved and the junkmen got their demands, or, enough of them to be satisfied. And then, the other shoe fell. ComYangPat announced that he and four staff officers and four women would be arriving at Ichang aboard the ISABEL to inspect the river and the Three Gorges. Now China is a hotbed of superstitions, and most Chinese respect them, indeed, live their lives wary of the misfortunes that could befall one who does not respect their powers; but they all pale when compared with the superstitions rampant in the navies of the world. One of the most fearsome superstitions in the US Navy is the one about having a woman on a warship. The idea itself is enough to make the most hardened chief's blood curdle. As far as could be determined the visit was without incident, no one was lost overboard, the PALOS's boilers did not explode, nor did she come to grief in the river. ISABEL had strong joss on that trip. As 1924 ended, sighs of relief could be heard the length of the Yangtze from the gunboat sailors of all nations there. They all looked forward to a peaceful 1925 now that the junkmen were happy. But it was not to be. 1925 in China was a year of wide-spread strikes, riots and all sorts of civil commotions. The nation seemed to be coming apart at the seams. Hardened veteran gunboat sailors could not remember a more trying year. Gunboats regularly sent landing parties ashore to protect their country's nationals as well as those of other countries if their own gunboats were busy elsewhere. Landing parties from US destroyers USS PAUL JONES (DD-230), VILLALOBOS, and USS STEWART (DD-224) as well as from the Royal Navy's HMS GNAT and from the Japanese and Italian gunboats were just some of the ones that went ashore that year.So wide spread and violent were the riots and demonstrations that at one time or another that year all the US gunboats in the Yangtze Patrol and the South China Patrol were busily engaged either on their own beats or on other beats as needed. LCDR Earl A. McIntyre's new command was the venerable VILLALOBOS. The ex-Spanish gunboat was still at it after all these years. McIntyre was enroute to China aboard the SS President Madison when he received orders on July 13, 1926 giving him command of VILLALOBOS. He steamed upriver in easy stages from Shanghai to Chiankiang, a British concession where he paid a call on the skipper of HMS WOODCOCK. He steamed next to Nanking, Wuhu, Kiukiang, and finally Hankow. He had barely settled in when he received news that the Chinese Communists, or Southern forces were on the move to Hankow. The Yangtze River was the natural barrier between China's north and south. Surrounding Hankow were the Nationalist or Kuomintang Army. McIntyre received orders to move VILLALOBOS upstream to Changsha, out of danger. VILLALOBOS ran aground enroute and had to be pulled free by a passing tugboat assisted by USS PIGEON (AM-47) and a Jardine & Mathieson steamer, arriving finally on August 30, 1926. McIntyre found Changsha an Eden. It was quiet, well kept and the foreigners there quite a sophisticated group of fun loving people. So peaceful in fact that McIntyre sent for his wife and children to join him. When they arrived the entire family rented a comfortable house complete with a battery of servants and settled in. HMS WOODLARK and the Italian gunboat ERMANNO CARLOTTO arrived and the rounds of soirees, galas, dinner parties, bridge games, and golf, and tennis matches.. Torn between Chinese fatalism and Western optimism they danced away the nights even though the densest among them could read the handwriting on the wall. The Communist armies were slowly creeping up the Yangtze Valley. It was just a question of time before they reached Changsha and who knew what would happen then.. On February 28, 1927 McIntyre received orders to get underway immediately for Hankow. His wife and children had been evacuated the previous month aboard HMS WOODLARK. McIntyre coaled PALOS at Lilangtan and wasted no time heading for Hankow arriving the on March 2nd. ComYangPat RADM H.H.Hough was safely ensconced on his flagship USS ISABEL while destroyers USS TRUXTUN (DD229), USS POPE (DD225) from the "Outside Fleet" rode at anchor in the stream.They were soon relieved by destroyers USS PRUITT (DD347) and USS HULBERT (DD342). The fighting was slowly coming to them. On April 3rd rioting had broken out in Hankow's Japanese concession. Two days later four Japanese destroyers arrived to evacuate their nationals. VILLALOBOS was sent downriver to guard the Socony-Mobil property where she met HMS TEAL and HMS SCARAB. On April 21st HMS VINDICTIVE and HMS CARLISLE arrived at Hankow. VILLALOBOS finally got underway for Shanghai and anchored on the Whangpoo river. Nearby six brand new gunboats were a-building. They were: The Generalissimo and the Communists The leader of the Nationalist Party and the Kuomintang was Generalissimo Chiang Kai-shek He had purged the Nationalist army of his Communist supporters and now stood alone against them and against the foreigners who had held China in thrall for decades. Everyone was his enemy. Nanking was the Nationalist's capital. The Communist armies had it in their gunsights and were moving troops to attack it. Nanking was also the spiritual and temporal capital of all of China's missionaries. They ran the University of Nanking and were firmly established there. To eject them was the goal of both the Nationalists and Communists. If the Communists could rid China of the foreign missionaries and Chiang too, China would theirs.That was the situation in Nanking in 1927. Five countries were so concerned for the safety of their citizens that they sent warships to Nanking to evacuate them if need be. The United States sent destroyers USS NOA (DD-343) , USS PRESTON (DD-327), USS JOHN D. FORD (DD-228), USS PILLSBURY (DD-227) and USS SIMPSON (DD-221). Great Britain sent the most warships; HMS WITHERINGTON, HMS PETERSFIELD, HMS WOLSEY, HMS VINDICTIVE, HMS CARLISLE, HMS WILD SWAN, HMS WISHART, HMS EMERALD, HMS GNAT, HMS VETERAN, HMS CARADOC and HMS VERITY. France sent MARNE, Italy sent ERMANNO CARLOTTO and Japan sent IJN HODERO, IJN SHINOKI, IJN MOMO and IJN KATATA. As the armed strength of the Communists grew, the Nationalist troops began to decamp. PRESTON and NOA sent landing parties ashore and evacuated 175 civilians and missionaries of all nationalities on March 21st. The Nationalist soldiers were in a panic. They had been unceremoniously deserted by their officers and faced destruction by the Communists.They rioted in Nanking and sacked the US, British, and Japanese Consulates killing the Japanese and British Consuls. Soldiers of the Sixth Nationalist Army systematically looted all buildings owned by foreigners. Whenever they encountered a foreigner, they invariably stripped him naked, beat him and robbed whatever valuables he might have on him. Women and children were subjected to unspeakable outrages as well as the men. As the situation deteriorated, the sailors in the warships in the river began to get impatient. Finally the order to fire in defense of their nationals arrived and they let loose with furious barrages. The shells fell all over the city while landing parties went ashore looking for endangered citizens to rescue. Shells were exploding all around the rescuers and rescued alike. Slowly, the sailors and civilians worked their way among shell craters, burning buildings and sporadic rifle fire to the river and safety. The Communists overcame the panicked Nationalists and captured Nanking. But it was all for nothing. The following year, 1928, the Nationalists re-captured it. The Generalissimo made some changes after this debacle. He divorced his wife and married a much younger woman named Mei-ling in a Christian church. He next aligned himself firmly with the international banking community in Shanghai.. The Six Sisters Arrive While Nanking burned upriver, the six new gunboats referred to earlier were taking shape at the Kiangnan Dock & Engineering Works in Shanghai. Their keels had been laid in 1926 and they were built in record time. Specifications called for a river gunboat displacing 385 tons over a length of 150 feet with a four-and-a-half-foot draft, twin screws capable of delivering a speed of fourteen knots. Propulsion was to be by twin diesel engines. Main armament was a pair of three inch high angle guns and eight .30 caliber machine guns. First to arrive and be commissioned was GUAM. She arrived on the river three days after Christmas 1927. Unlike her five sisters, she did not have diesel power. Her power plant was a triple expansion engine powered by an oil-fired boiler. As her first skipper, LCDR R.K.Awtrey read his orders, swarms of curious Chinese watching the commissioning ceremony set off thousands of firecrackers to ward off the multitudes evil spirits that were waiting to follow in her wake. The firecrackers and good wishes failed to bring about the desired effect. GUAM was destined to sail in four different navies under five names. But all that was in the future. For now she was a spanking new ship that carried four line officers, a doctor, a crew of 50 sailors and several coolies, who at US$5.00 per month plus whatever they could "squeeze" from the crew, were more than happy to do all the dirty work aboard. ADM Yates Stirling, ComYangPat put GUAM right to work after she had completed a shakedown cruise to Chungking, a mere 1300 miles upriver from Shanghai. GUAM had handily overcome the rapids with her 1900 horsepower and her crew was waiting for an assignment. Stirling ordered her to escort four Standard Oil Company tankers, Mei Lu, Mei Ying, Mei Foo and Mei Hung. GUAM took some fire from the river banks on the voyage upriver, but no one was hit and no damage was done.

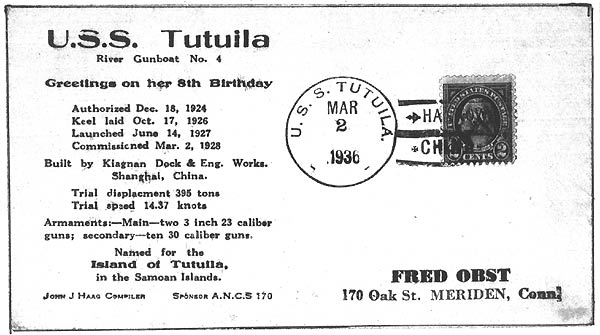

Figure 13, USS MINDANAO The next five were launched like clockwork by July of 1928. TUTUILA was nicknamed "Tutu" and had a rather unorthodox christening ceremony. Her sponsor, Beverly Pollard was a devout Roman Catholic schoolgirl of fifteen years. As she swung the magnum of champagne agaist Tutu's stem she completely forgot what she was supposed to say. Instead she uttered these words, duly recorded at the time: " I christen thee USS TUTUILA, in the name of the Father, the Son and the Holy Ghost" .The blessing must have worked because Tutu survived WWII in Allied hands. OAHU and PANAY strayed somewhat from the original specifications. They were 30 feet longer and 80 tons heavier than GUAM and TUTUILA and the last of the six, LUZON and MINDANAO, were longer still by 48 feet and heavier by 200 tons. MINDANAO was sent to the South China Patrol and did not serve on the Yangtze with her sisters. The six were a marked improvement over what had been before.

Figure 14, USS LUZON Comparisons are odious but necessary. What were the ex-Spanish gunboats like? Take ELCANO for instance. She had been built in 1885 of wrought iron in Spain. She displaced 625 tons over a length of 165 feet and a beam of 26 feet. She carried four 4-inch naval rifles, four six-pound cannon and an assortment of automatic weapons. She was nicknamed the "Yangtze Sprinkler" because every time her antiquated engine went through the stroke cycle its cooling pump squirted a geyser of water up into the air. Her pair of Scotch boilers were bedded down side by side so that when the water was drained from one boiler she took a decided list that was so acute walking around the boat became perilous. With both boilers on line she took forever to raise enough steam to get underway and when she did manage to get underway she had to stop every three hours to clean the clinkers from her boilers. The officers quarters were so tiny the officers had to step out into the adjoining wardroom to put on their trousers. Sanitary facilities were inadequate when they worked; refrigeration was non-existent and the electrical plant was archaic. Life aboard the other ex-Spanish gunboats was a variation of life aboard ELCANO. In November of 1927 ComYangPat ordered ELCANO to leave Ichang where she had been the station ship and to proceed to Shanghai where she would be the receiving ship for the crews asssembling there to man the six new gunboats. When all of the new gunboats were properly manned she was decommissioned on June 30, 1928. She and VILLALOBOS were towed out to sea and sunk by naval gunfire on October 9, 1928. Changsha was next on the list of cities to be attacked by the Communists. PALOS, HMS TEAL and IJN KOTOGA stood by ready to send landing parties ashore to rescue civilians. At 10:00 PM in the evening of July 27, 1928 the three gunboats sounded their sirens as a pre-arranged signal for the foreigners in Changsha to evacuate the city. Fourteen American citizens chose to leave. PALOS took them downstream away from the fighting and rendezvoused with HMS APHIS on the 29th and left them with her. PALOS then headed back to Changsha where her comprador, a Chinese gentleman named Fu Chang who was usually a natty dresser, as befitted his rank and station, went ashore in Changsha dressed as a poor coolie for a look around. What he saw was reported to PALOS's skipper LCDR R.D. Tisdale. Tisdale ordered the crew to General Quarters. He gave the gunners orders to fire at anything they saw and they did. Both banks exploded in clouds of dust and gunsmoke as HE shells exploded against the hillsides and tracers filled the night sky with a spectacular fireworks. PALOS suffered some damage but it was all to her sides and upper works. Over a hundred Chinese bullets had found her but luckily, no one was killed and only one sailor had been wounded in the fusilade. She had fired 67 rounds of HE shells from her three-inch and about 2000 rounds from her Lewis guns. PALOS had been joined in this foray by the Italian gunboat ERMANNO CARLOTTO and HMS APHIS. The latter's two six-inch rifles added mightily to the fireworks. The Communist withdrawal from Changsha was due in no small part to the action of the warships. As the Communists withdrew, the Nationalist soldiers found a renewed fighting spirit and marched into the city. They even declared martial law but lifted it after a few days. PALOS remained at Changsha until November 15th when she headed back to Shanghai. Along the way she was scheduled to meet GUAM below Changsha. As GUAM approached Tungting Lake she came under fire near Yochow. Seaman Samuel Elkin took a round in the chest and died. GUAM's skipper ordered the three-inch guns to fire. They poured 34 rounds of HE at the shooters who soon realized the folly of going up against a cannon and fled. HMS BEE received the same welcome some time later in exactly the same place. She answered with her six-inch naval rifles and silenced the shooters.