|

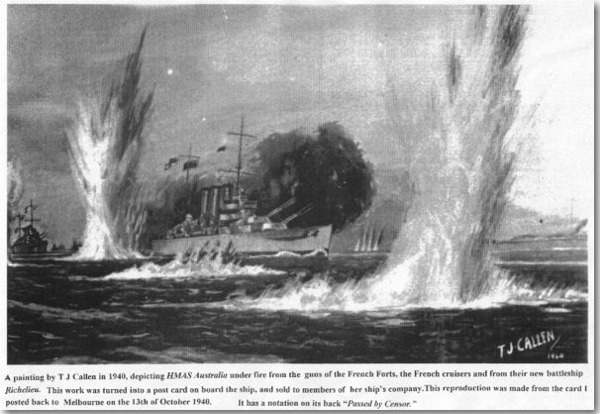

"Operation Menace." September 23, 24, 25, 1940. HMAS Australia and the debacle at Dakar with General Charles de Gaulle

In September 1940, I was eighteen and had already served as a Midshipman in HMAS Australia for over a year. We had been attached to the Home Fleet based in the desolate North of Scotland at Scapa Flow. Australia had carried out patrols between the Faroe Islands and Greenland; sweeps into the Greenland sea which took us north as far as Bear Island, less than a 1000 miles from the North Pole; and patrols in the east to Tromso off the coast of Norway. The weather was usually cold, and we often encountered extremely rough seas and gale force winds. Life at sea was not pleasant, one could rarely keep warm, and how we yearned for some lovely Australian sunshine, but Australia seemed as far away as the moon, our only link with home being mail; and that was usually months old by the time it reached us.

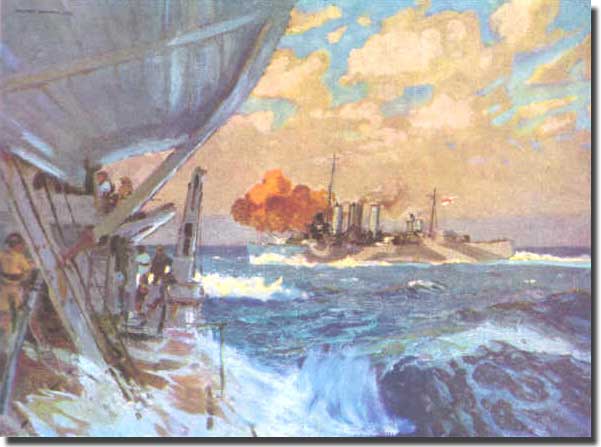

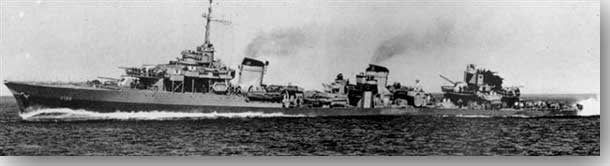

HMAS Australia, firing on the Forts at Dakar The last day of August 1940 found my ship en route from Scapa to Greenock on the Clyde. We passed the torpedoed liner, Volendam, being towed stern first by an Admiralty tug, she was well down by the bows. We entered the Clyde at 1100 the next day, and as the ship proceeded up the river I found the scenery quite beautiful, a complete contrast to Scapa Flow. On both banks, the hills brilliantly green, rose up into the distance; we passed through the protective boom, and anchored off Greenock. On the 5th of September we embarked French flying officers and two Cauldron Renault aircraft - quite similar to our Gipsy Moth. The next day we cleared the Clyde, and turned south, proceeding under sealed orders. For the following week we continued steaming on a south westerly or southerly course, with the weather now becoming decidedly warmer, as we finally shook off the cold Scottish and North Atlantic weather. We reached Freetown, West Africa on the 17th. of September, the weather now glorious - and we basked in the welcome sunshine. At anchor in Freetown harbor was a large naval force: Two battleships, Barham and Resolution, aircraft carriers Ark Royal, Argus, and Vindictive, the 8 inch gun cruiser Devonshire, and the old seaplane tender Albatross that had been built in Australia, and was transferred to the Royal Navy as part payment for the County class cruisers Australia and Canberra, seven destroyers, two hospital ships, two French gunboats, and a French sloop. A number of troopships were also present, aboard these were landing punts, flat bottomed, fitted with twin propellers that ran within tunnels to prevent fouling, their twin rudders also housed within the tunnels. The punts drew only 18 inches, and were built from bullet proof steel, and had a speed of 12 knots. The troops were a combination of Free French soldiers under the command of General de Gaulle, and some thousands of Royal Marines. The two French aircraft we had transported, together with the Frenchmen to fly them were all transferred to Ark Royal. We embarked 8 inch high explosive shells, so it looked as if we were preparing for a bombardment. The force then sailed from Freetown, and turned north, meeting the British cruiser Cumberland at 0800 the next morning, the 19th. of September. She had been patrolling off Dakar, and we were detached to take over these duties. Winston Churchill and his war Cabinet had decided to assist de Gaulle in a landing of Free French forces in West Africa, our destination is Dakar. This was the main port of French West Africa squatting ideally on the trade route from the Cape to Britain, and until the capitulation of France, extensively used by British merchant ships. However, Dakar had remained loyal to the Vichy Government, and was now available as a base for enemy submarines, and armed merchant raiders to operate against our trade and our Navy. De Gaulle believed that he could prise Dakar away from Vichy control, and bring them over to the Free French cause. Shortly after assuming the patrol off Dakar, Australia closed up at action stations, the reason soon apparent; three French cruisers Gloire, Georges Leygues, and Montcalm all of the Galissoniere class were in sight. These were 6 inch ships, each carrying 9 by 6 inch guns in triple turrets, 8 by 3.5 inch AA guns, 8 torpedo tubes in 4 twin mountings, and fitted with a catapult, for use by 4 aircraft. Reported speed was in excess of 32 knots, and their aircraft are recovered by a unique method. A type of steel mesh mat was lowered out of the square stern, this sloped down into the water, the aircraft landed astern, and taxied up onto this mat, to be hoisted aboard by a stern crane. Our task was to prevent these 3 French cruisers from reaching Dakar and reinforcing the naval force already in that port. Cumberland joined us and we shadowed them from ahead, as they proceeded on a southerly course. At 1730, we closed these ships for night shadowing, night fell quickly as it does in the tropics, and the French ships turned to the north west and increased speed to give us the slip. They were soon out of sight, as we worked up speed to give chase. A heavy cruiser takes time to work up to full speed, not at all like driving a car where one may plant your foot on the accelerator for an instant response. At 2100,we visually sighted one of the Frenchmen on our starboard bow, our capture, Gloire, who had broken down and could only proceed at 4 knots. Cumberland joined by Devonshire, were after the other two French cruisers, but they subsequently reached Dakar, having out run the British ships. During our chase, Australia worked up to 32.8 knots, needing 82,000 horse power to achieve this speed. The ship's designed horse power was 80,000, and we were over six months from our last docking, carrying a fouled bottom, and were also well above our design tonnage. Praise must be due to our engine room staff who kept the ship steaming at full speed, under most difficult conditions for almost three hours. Gloire was kept in sight all day, and now decided that she could steam at 17 knots. She was ordered to steer for Casablanca, and warned we would "sink her" if found in the vicinity of Dakar. Captain Broussignac in Gloire indicated he would proceed quietly to Casablanca, we accepted this assurance, and he proceeded alone, we parted company and proceeded to the west. Gloire reached Casablanca on the 24th. of September.

If the French airmen were successful, representatives of General de Gaulle will enter the harbor in a motor boat fitted with a loud speaker, their objective to convince the navy to switch to de Gaulle. Here again I am doubtful, Brigadier Charles de Gaulle is a relatively unknown army officer who has fled to England, to set up the Free French movement. He is junior in rank to both the Vichy leaning Army and Naval Officers ensconced at Dakar, I suspect his call to submit to his authority may well fall on deaf ears, and I don't like his chances of success. Naval personnel at Dakar will still be angry at the way the Royal Navy had sunk French warships and killed many of their colleagues at Mers-el-Kebir near Oran. But, who am I, as an 18 year old Midshipman to pass premature judgment on this plan by de Gaulle to assert his authority over Dakar and its service people there? These thoughts are penned in my Midshipman's journal as we steam off Dakar. The real objective is to take Dakar, convert it, preferably without bloodshed. These thoughts were penned in my Midshipman's journal as we steamed off Dakar. The real objective is to take Dakar, convert it, preferably without bloodshed If this plan was not successful, French troops would attempt a landing, and try to convince the local government to declare Dakar on the side of de Gaulle. Failing this move, the forts would be bombarded, and Marines landed to attempt to take the town. These three plans were code named "Happy," " Sticky," and " Nasty." We joined the fleet with the troopships, and now proceeded towards Dakar. Monday, the 23rd. of September 1940 This day dawned quite hazy, with visibility down to about a mile and a half. The French aircraft flew off from Ark Royal, and landed at Wackem aerodrome within Dakar. Propaganda leaflets were dropped over the town by Fleet Airarm planes, it seemed to be a Paper War. De Gaulle's representatives in a motor boat entered Dakar Harbor, flying the French flag, and a white flag of peace - but were fired upon - and nothing further was heard from them. Battle flags were hoisted - the Australian Ensign at the fore, a large White Ensign at the main, and our usual Ensign at the gaff. I recall the huge surge of pride I felt observing our Commonwealth Ensign flying at the foremast for the first time in this war. At 1000, ships were reported to be moving out of the harbor - we were ordered to turn back these French destroyers and sloops - we fired a warning shot, they turned about and returned to harbor. The forts now engaged us at close range, and we rejoined the battleships. Our force closed the forts and the battleships engaged them - in turn, the forts responded with 9.4 inch and 5.4 inch gunfire. Submarines were reported underway, and a British Destroyer HMS Foresight was hit, the shell passing right through her hull, making a neat hole on entry, but a huge ragged hole on exiting. Dragon scored a hit on a submarine, but was herself hit by the shore batteries. Two shells from the fort guns fell very close to Australia as the force turned away, but Cumberland was hit by a 9.4 inch shell. At our Action Stations, we were served Action Stew! My action station was in the High Angle Transmitting Station, situated well below the water line, deep in the bowels of the ship. Completely blind visually to whatever happened above the deck -to keep me informed about the action, I had to rely on a running commentary linked by a phone head set to the High Angle Control Position, located high up in the ship. When the French shells landed alongside, close to the ship, fragments could be heard striking the ship's side, well below the waterline- very, very scary indeed! Aircraft reported an enemy destroyer in the Baie de Gloree, to the south and eastwards of the inner harbor. Australia was detached with three destroyers to investigate. At 1624 the enemy was in sight, we opened fire at 1626, three minutes later she was on fire from stem to stern. We ceased fire, although termed a destroyer, this ship, the L'Audacieux, was in fact a light cruiser, mounting 5 by 5.5 inch guns, carried torpedo tubes, and was capable of very high speeds. One of our escorting destroyers was sent off to pick up survivors, but the forts opened fire on her, and it withdrew. This French ship burned for 36 hours and eventually beached near Rufisque.

By 1640, we had rejoined the battleships, after a quick decisive action. It was decided to attempt a landing close to Rufisque by Free French troops from French sloops and the vessel President Houduce. By 1720, troops were trying to get ashore, withering fire from a strong point overlooking the beach thwarted this attempted landing, five men were wounded and two, subsequently died, the attack was called off. General de Gaulle declared " He did not want to shed the blood of Frenchmen for Frenchmen." We had been closed up at action stations all day; sunset was welcomed, so we could now resume a lower degree of readiness for the night. Tuesday the 24th. of September 1940 Australia and Devonshire joined the battleships and closed on Dakar, these two 8 inch gunned cruisers were detached to engage the Vichy cruisers Georges Leygues and Montcalm, that had escaped from Cumberland and Devonshire and made it into Dakar. Visibility was again poor, we could only fire at the gun flashes emanating from these French ships underway south of the harbor entrance, we were now attacked by a Glen Martin bomber flown by Vichy French personnel, and a stick of six small bombs fell close to our starboard side. Ironically, these bombers were sold to France by America prior to their capitulation to Germany. Georges Leygues and Montcalm retired behind merchant ships in the harbor, and we withdrew southward. Our battleships engaged the forts, and the Richelieu, a new French battleship which was in port, she mounts 15 inch guns and was a most formidable adversary. We were again attacked by a Martin bomber, this time dropping a large bomb very close to our port quarter, deep in my dungeon I felt the whole ship shudder, shaking herself as a dog does when wet, no damage done, but I hated not being able to see the action for myself. Many of our company, of necessity, served at action stations unsighted, below decks, as did I, but given a choice (which will never happen) I would always opt for an action station where I could know what and when things happened. What wishful thinking on my part, I needed to accept my lot, and perform to the utmost of my capacity. A French submarine surrendered, and a second one was sunk by our aircraft Sunset brought the close to yet another day of action.

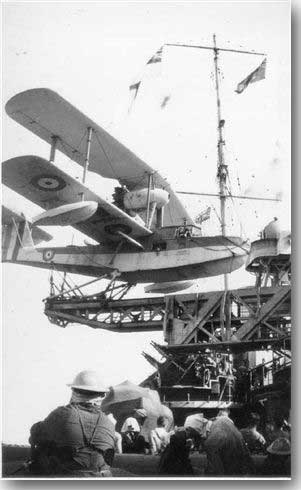

The plan for today, the battleship Resolution would attack Richelieu, the battleship Barham and cruiser Devonshire the forts, whilst we were to take on the Georges Leygues and Montcalm holed up in Dakar harbor. Our Walrus was spotting our fall of shot when the Frenchmen disappeared behind a smokescreen. At one stage we were under fire from Richelieu, the forts, and the cruisers, the French made use of an ingenious device to distinguish the spotting of their shell bursts. Each salvo was marked by a certain colour, Richelieu used yellow, the forts white, and the cruisers green and red. We were almost bracketed by a rainbow! Although the range was between 24 and 28,000 yards Australia was twice hit by 6 inch shells, one passed under the rear end of X turret, as it was trained forward, and then exploded in the unmanned Captain's galley, which was totally wrecked, leaving a large neat hole behind in the deck, but fortunately no one was injured. The second shell passed through the ship's port side, entered the Engineer's Spare Gear Store where it blew up, most of the explosive shock was taken by the spare gear, but the armored belt was penetrated into the engine room, where the port distiller was wrecked, again, no causalities. With an evaporator out of action, fresh water manufacture became reduced, and water immediately became rationed. If X Turret had not been trained forward, the first shell would probably have penetrated the gunhouse, and then exploded with dire results. Our aircraft had just reported that our shells were falling both sides of the French cruisers, i.e.. we had found their range, and bracketed them with our fire, one would expect the next salvo to provide direct hits. We observed the Walrus to suddenly plunge into the sea, shot down by a Curtiss fighter, which in turn, was then destroyed by AA fire from one of our battleships. All three aircrew were lost. The cruisers and battleships now withdrew, and Resolution was struck by a French torpedo, and took on a heavy list to port, as our destroyers screened this stricken ship an enemy bomber attacked, but we drove off this attack with accurate AA fire. We were busy in my transmitting station helping to repel this bomber attack, and were pleased with our performance, when the attack was broken off and the bomber flew away. The attacking force now left the Dakar area, and with Barham taking Resolution under tow, Australia supported them from their port quarter, as we withdrew and proceeded south at a slow speed. Difficulties of Operation Menace at Dakar I am reporting my thoughts and opinions recorded in my Midshipman's journal at the time of the Dakar expedition, of course, stated with all the wisdom of an 18 year old.

Operation Menace was laid on for political reasons, with Winston Churchill showing support for the prickly General Charles de Gaulle. There was no other Free French figure on the horizon, and it was thought this operation may prop up the General, and provide a rallying point for those wanting to support his movement. Secondly, President Franklin Roosevelt was anxious that Dakar did not come under German influence. Conclusions The port, and surrounding fort installations could only have been taken with a large land force, and a powerful modern Naval presence, but without any Free French participation. This operation must be judged a complete failure on our part, a battleship badly damaged and put out of action for a considerable time when every Fleet unit was desperately needed to support the Naval war, and the strong possibility of a German invasion of England. Three cruisers and one destroyer all hit by enemy shells, plus Fleet Airarm and our Walrus aircraft shot down. On the other side of the coin, two destroyers and one unknown vessel destroyed, one submarine sunk and a second one surrendered, two possible hits by 15 inch shells on Richelieu, and a possible torpedo hit on one cruiser. By removing two submarines, part of the menace to our convoys was eased, however, in the final analysis, our basic objective to bring Dakar over to the side of the Free French movement, was not achieved. HMAS Australia and her crew had performed with ability, her ship's company could indeed be proud of their baptism of fire.  |

Wednesday the 25th. of September 1940.

Wednesday the 25th. of September 1940.