It is possible we may have exchanged correspondence of some form in the past but if not it is only prudent I introduce myself. I am an ex sub aqua diving instructor who was forced to give up a varied and enjoyable carer in diving because of serious health problems in 1999. When not instructing my passion was for deep diving, however, the wreck of the

Rohilla was always important to me. Being the biggest wreck in shallow water, close to the port it was my preferred wreck for introducing my students to open water diving.

After leaving my diving career behind me I remained in touch with the sport diving community and the Rohilla seemed a logical choice for my third book “Into The Maelstrom - The Wreck of the Rohilla.” It is an ever changing project and I am always finding new developments to go at, I often receive e-mails requesting information from people doing their family tree and finding they had an ancestor who was involved when the ship was lost.

Your website appears to be extremely interesting and comprehensive and you are to be congratulated on your achievements. Along with my HMHS Rohilla website and my other four websites I can appreciate how time consuming it can be, it must have been a mammoth task to have 2471 articles on your website site.

I have attached some photographs of the Rohilla and a summary of the tragedy which you are free to use on your website should you choose to include the Rohilla.

His Majesty’s Hospital Ship Rohilla -Colin Brittain

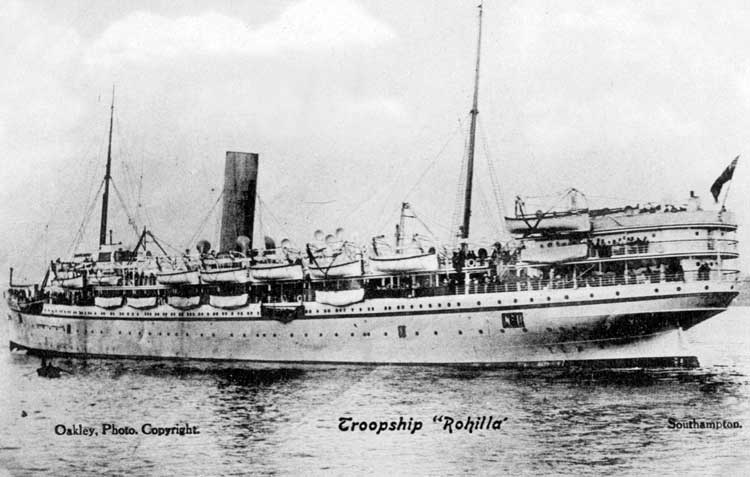

The Rohilla was a steel-hulled 7,144-ton luxury steamer that measured: 140.28m by length, a 17.14m-beam and a 9.29m-draught. She was built by Harland & Wolff, Ltd as Yard No. 381 in November 1906.

She was launched as a passenger / cargo steamer on 6 September 1906 for the British India Steam Navigation Co. (BISNc) Glasgow. The twin bronze propellers were powered by two powerful steam engines which developed 1484 hp using six boilers giving the ship a service speed of 16 ½ knots. The ship was one of the earliest to be equipped with the latest wireless telegraphy.

Almost from the day she was built, the Rohilla was used as a troop transport, ferrying troops between Southampton and Karachi. Her Captain, David Landles Neilson was fifty years old and had spent his whole career at sea with the BISNc. tasking command of the Rohilla the day she was launched.

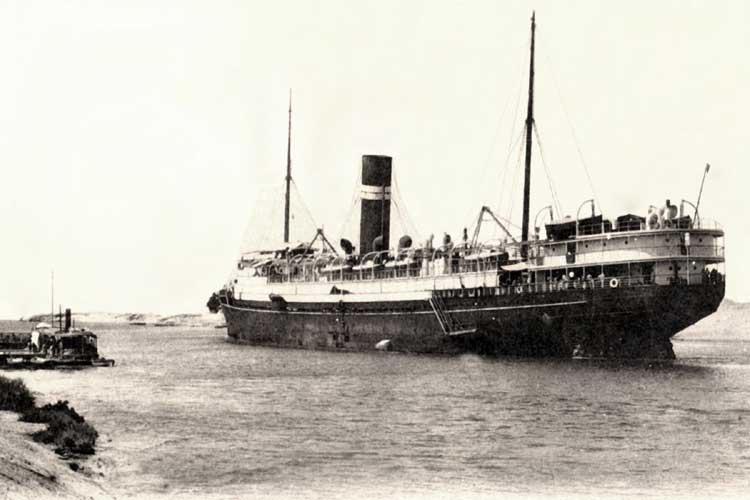

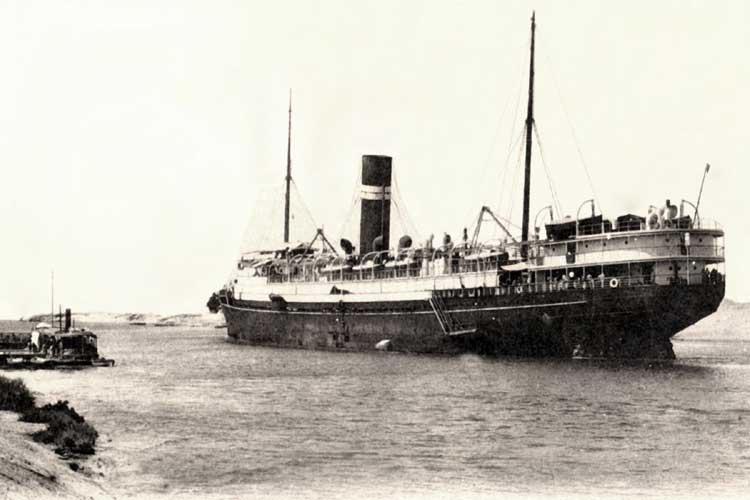

Port Said

When war broke out, he and his officers remained at their posts albeit under the command of the War-Office. In the summer of 1914, the Rohilla was requisitioned by the Admiralty and converted from a luxury passenger liner into Hospital Ship No. 2, her passenger accommodation was converted into wards, and operating theatres added. The ship was ordered to the naval base at Scapa Flow, to join Admiral Jellicoe’s Grand Fleet.

During August 1914, Prince Albert, spent some time as a patient with appendicitis on board the ship, he later became King George VI. The ship remained at Scapa Flow for a few weeks, before transferring to Captain Neilson’s home town port of Leith, near Edinburgh. The only patient at that time was a Royal Navy Gunner who had broken his thigh and was deemed too ill to be moved elsewhere.

At 1300hrs on 29 October 1914, Rohilla left Leith Docks bound for Dunkirk, to evacuate wounded troops from the Western Front. She left Leith carrying 229 people, including 127 crew, 100 medical staff, a Roman Catholic priest, the ships only patient and the ship’s cat. The ship rounded Bass Rock on the Firth of Forth and steamed down the east coast. By the time she reached the Outer Farne Islands, a full blown ESE storm was raging and the course laid in by ‘dead reckoning’.

At about 0330hrs on 30 October, Albert Jefferies a local Coastguard officer at Whitby, realised the ship was heading directly towards a treacherous reef system known as Whitby Rock. He signalled her with a Morse lamp and switched on the foghorn to warn her of the imminent danger to no avail.

At approximately 0410 hrs the ship ran onto the rock scar, a solid submerged reef some 600 metres out from the towering cliffs of Whitby below the majestic Abbey. Although there was a buoy warning of the danger its bell and lights were extinguished under wartime regulations. In the darkness and with a terrible storm raging, Captain Neilson supposed that they were some seven miles northeast of Whitby and his first thought was that his ship had struck a German mine.

He ordered the engines ‘Full Astern’ to bring her to a stop, knowing he was faced with two fearful alternatives; seeing the ship founder where it was with greater loss of life, or run the vessel ashore in an attempt to ground the hull in shallow water. Turning the wound(ed) ship towards the shore he had no idea that just a few moments later the ship would run hard aground mortally wounded just south of Whitby.

Albert Jefferies set off the maroon rockets to alert the lifeboat crews and Rocket Brigade.

The angle at which the Rohilla was jammed on the Scar presented her broadside to the waves. Her bow had risen over the edge of the rock forcing the stern lower into the water, the sea constantly washed over the well decks and spray was thrown high above the height of the bridge. Captain Neilson ordered all hands to lifeboat stations but five unfortunate seamen were known to have been washed overboard and drowned as they made their way to posts. With twenty lifeboats there were more than enough places for those on board, provided that the boats could be launched. When the ship hit the Scar most of the crew were below decks asleep and would have known nothing until the point of impact.

It is likely that those on the lower decks would have died quickly as the sea flooded in. Putting the engines full astern to try and free the ship from the rock allowed water to flood down into the lower decks, stopping the engines the lights went out in a very short period. As the remaining souls rushed from their cabins they did so leaving behind all their possessions, remaining clad in makeshift garments, many in just their night clothes.

The Rescue Attempts Begin

Thomas Langlands, the coxswain of Whitby's No. 1 lifeboat, Robert & Mary Ellis, a native of Seahouses in Northumberland, knew that the lifeboat would be dashed to pieces before it could be launched in the terrible sea conditions and it would not have been practical to try and row the No 2 boat, the John Fielden out through the harbour mouth in such a storm, as both boats were rowing lifeboats manned by 14 crew members. All they could do was to wait until daylight and hope the storm had abated a little by then.

The Rocket brigades were quickly on the scene and made drastic efforts to reach the ship to set up a bosun’s chair, defeated by the terrible conditions. At around 0700 hrs, the ship’s stern broke away sinking into the deeper water sweeping away many people to their deaths. The continued pounding waves washed away or smashed up most of the ship's lifeboats.

The morning brought no improvement in the weather, and an audacious plan was hatched to manually manoeuvre the John Fielden across the rock scar. With the assistance of the townsfolk the thirty six foot lifeboat over the stone breakwater and dragged it over the rocks, it no easy feat and took over two hours to get the lifeboat near to the wrecked ship almost a mile away. Despite their best efforts the lifeboat was holed in two places, but the cork filling was considered strong enough to keep the vessel afloat and withstand the fourteen man’s crew’s attempts to row her out to the Rohilla. The lifeboat made two successful journeys taking seventeen and then eighteen people off the stricken ship.

After the second trip to the wreck, the John Fielden was deemed too badly damaged to make any further journeys; she was dragged up the beach and left to the elements. Desperate to be saved many people attempted to make the swim to shore, but the strong tides and treacherous conditions were simply too much for many of them and they were swept to their deaths. Many local people risked their own lives wading chest deep into the raging water to pull half dead survivors out

Meanwhile, telephone calls had been made to the lifeboat stations at Scarborough and Teesmouth, asking for assistance. The steam trawler Morning Star towed Scarborough’s lifeboat Queensbury out at 1530 hrs that afternoon and after battling mountainous seas, they arrived off Saltwick Nab at 1800 hrs. By then it was pitch dark and they were unable to get close to the wrecked ship. Nonetheless the lifeboat and trawler both stood by all night just in case an occasion arose where they might get alongside the stricken vessel. They made repeated attempts the following day, but were beaten back each time after so long at sea the men were exhausted leaving them with the hard decision to return to Scarborough.

The motorised 12 metre self righting lifeboat Bradford IV, stationed 22 miles away at South Gare, Teesmouth, made an attempt to reach Whitby sadly though the pounding of the huge seas caused a serious leak and she was herself towed back to her station.

At 0700 hrs on the Saturday morning, the conditions lessened a little and the Robert & Mary Ellis was launched. Coxswain Langlands took her out to sea to await the arrival of the steam tug Mayfly which had come from Hartlepool to help. She arrived at 0800 hrs and took the lifeboat in tow, yet even this attempted was thwarted by rough seas, which prevented her closing on the Rohilla. Coxswain Langlands discussed the situation with James Hastings, Coxswain of Hartlepool’s No. 2 lifeboat, who was on board the Mayfly reluctantly deciding to return to Whitby.

The crew of Upgang lifeboat William Riley knew that facing the sea it was impossible to launch the lifeboat into the surf under such conditions; however, spurred on by the exploits of the John Fielden, a plan equally impressive was hatched. The lifeboat was taken overland, a journey of more than three miles by road, and along some very steep hills. Using six horses and over a hundred people, the 36ft lifeboat was positioned on the top of the cliff adjacent to the Rohilla. Long lines of men hung onto lines attached to the lifeboat, which was then perilously lowered bodily down an almost perpendicular cliff, 200ft to the bottom, a feat which was amazingly completed in just two and a half hours.

Once at the bottom however everyone was defeated that nothing could be achieved as they could not launch the lifeboat due to the extreme conditions much to the disappointment of Coxswain Robinson and his crew. Any question of launching was abandoned for the time being, with the men remaining assembled in readiness should an attempt be possible later on. The crew of the William Riley made some attempts at launching the boat but despite their best efforts and repeated attempts to reach the wreck, they were totally exhausted and forced to give up and returned to shore.

The Henry Vernon

At 1615 hrs in desperation, an urgent telephone message was made to Tynemouth, requesting their help not long after the 12 metre self righting motorised lifeboat Henry Vernon was launched. Built in 1911 and powered by a 40 hp Tyler petrol engine, she was also still equipped with oars and an auxiliary sail. She travelled 40-miles south during the night in the same hazardous conditions the larger Rohilla did, finally reaching Whitby harbour at 0100 hrs on the Sunday. It was decided to take on barrels of oil which were to be used to lessen the effects of the heavy seas around Rohilla, when a rescue attempt was to be made.

At 0630 hrs the Henry Vernon headed out of the harbour, with her Tynemouth crew, Lieut. Basil Hall the District Inspector of Lifeboats and also the Whitby 2nd Coxswain, Richard Eglon who was to at act as Pilot.

Some three days after running aground the Rohilla those left on board were in a dreadful state. The lifeboat made her way out to the wreck and when they were about 200 metres to the seaward side of ship the crew poured the oil onto the water's surface. This had an almost dramatic effect on the foaming white water lowering the effects of the swell, enabling Coxswain Smith, with great courage and determination, to manoeuvre the Henry Vernon alongside the Rohilla’s bridge the only part of the Rohilla left above water despite the boat being almost swamped by the massive seas.

The only survivors left lowered ropes and began lowering themselves down into the lifeboat, soon forty men had managed to get into the lifeboat. Just then two enormous waves washed over the wreckage crashing down onto the lifeboat. They managed to clear much of the water as the remaining ten men were secured in the lifeboat the last man being Captain Neilson and the ships cat. The lifeboat began motoring away from the wrecked ship but as she cleared the stern of the wreck, another gigantic wave struck the lifeboat broadside on. The boat rolled right over on her beam ends ‘hanging’ as though she would not survive yet within seconds came upright again and carried on back out to sea.

Coxswain Smith brought the Henry Vernon safely back into Whitby harbour, and was greeted by hundreds of people who had come out to see the final fifty saved. When the Henry Vernon made its way back to Tyneside it was met by hundreds of onlookers and the rapture of applause.

The lifeboat crews performed some very heroic feats in horrendous conditions. Altogether, some 139 people were rescued from the 7,409 ton hospital ship, with at least eighty five of them saved by the brave RNLI lifeboat crews. Unfortunately, eighty four people lost their lives, including sixty two of the ship's crew, on that terrible day in 1914.

The Lifeboats involved

Official Number(O.N.) Name Period Launches Lives Rescued Cost

350 Bradford 1911-1917 10 12 £696

379 John Fielden 1895-1914 40 62 £305

484 Queensbury 1895-1901 15 8 £348

588 Robert and Mary Ellis 1908-1934 15 11 £887

594 William Riley of Birmingham and Leamington 1919-1931 31 10 £722

613 Henry Vernon 1911-1918 26 206 £3,664

At the inquest, Captain Neilson and his four senior officers gave evidence and the seven mile calculation error was never satisfactorily explained, however they were all of the same opinion that the vessel had first struck a German mine. Many local people firmly believe that the ship’s course took her over the eastern end of the submerged Whitby Rock and it was that which she first struck.

For their bravery Coxswain Thomas Langlands, Coxswain Robert Smith and Captain H.E. Burton RE were awarded the RNLI's gold medal for conspicuous gallantry and silver medals were awarded to Second Coxswain Richard Eglon, Second Coxswain James Brownlee, and Lt. Basil Hall RN. The silver medal was also awarded to George Peart who bravely went into the violent surf repeatedly to help people who had attempted to swim ashore from the Rohilla. The RNLI's ‘Thanks on Vellum’ were awarded to Coxswain Pounder Robinson and to Second Coxswain T. Kelly of the Upgang lifeboat, while the crews of the lifeboats involved, were honoured by some extra cash.

Captain Neilson was even honoured with the Bronze Medal of the ‘Royal Society for the Prevention of Cruelty to Animals’ for saving the ship’s cat. The rescue of people from the wreck of the Rohilla still remains one of the RNLI’s greatest achievements.

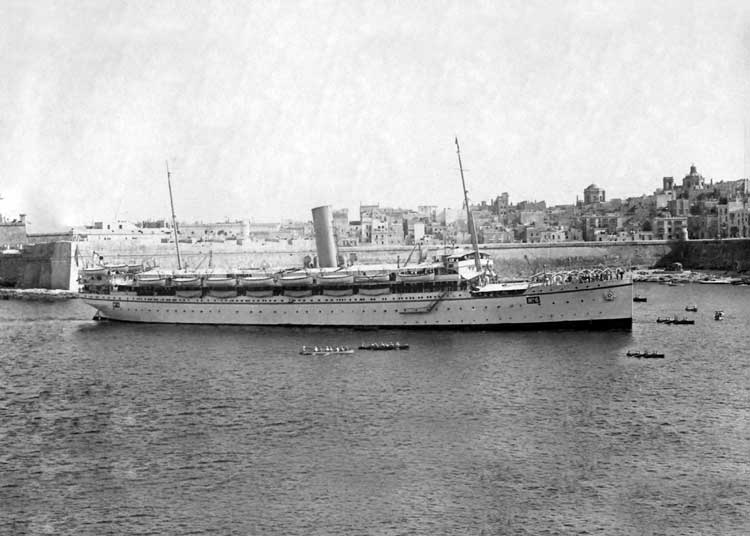

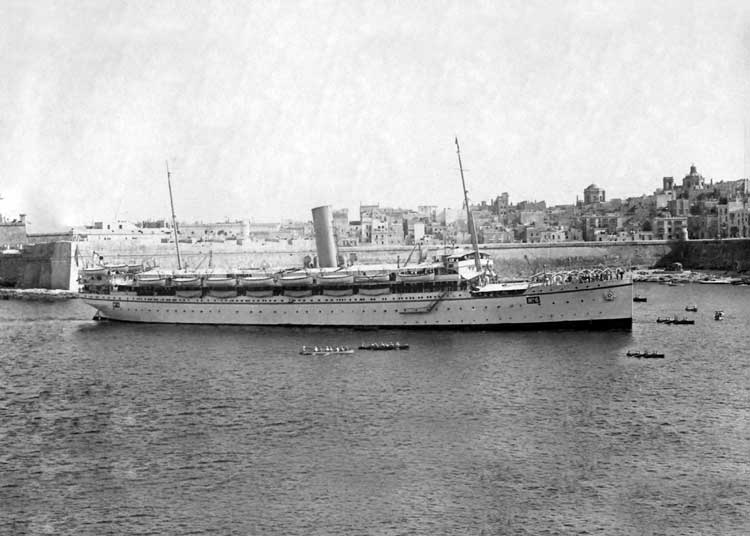

Malta 1910