|

England versus Spain. The Defeat of the Spanish Armada. 1588

Getting rid of an unwanted wife.

Henry VIII, generally accepted as the Father of the Royal Navy In 1501, Catherine not quite 16, set sail for England, and on the 14th. of November that year she was married to Arthur in the old St Paul's Cathedral in London. Within but six months Arthur had died, and in only another fourteen months Catherine was betrothed to the future King, Henry the VIIIth. In 1509, she became the first of the six wives taken by King Henry the VIIIth. and was crowned Queen of England on the 24th. of June. She soon fell pregnant, only to have a still born daughter the following January, without wasting any time, she was again pregnant, to give birth to a son, Prince Henry, on the 1st. of January 1511, this was the son so dearly wanted by the King. Alas, the new prince lived for only 52 days, and Catherine did not have much luck with her children, another miss carriage, then another short lived son, finally the birth of a daughter Mary, on the 15th. of February 1516. However for the King, this was the last thing he wished for, a daughter, no, he longed for a son, a male heir to follow him as a future King of England. Thus the seeds of Catherine's downfall and fall from favour were sown with the birth of Mary. Henry was totally frustrated by this lack of a male heir, he had already cast his eyes around for his next wife, he was hopelessly in love with Anne Boleyn, one of his wife's ladies in waiting, whom he had managed to get pregnant. The King now petitioned the Pope in Rome for an annulment of his marriage to Catherine, but given the sanctity of marriage in which the Roman Catholic Church believed, there was no way this annulment would ever be forthcoming.

Anne Boleyn Henry was forced to find some solution to his problem of getting rid of Catherine as his wife, and to reject the power of the Pope in England. He turned to the Archbishop of Canterbury, Thomas Cranmer, who granted him an annulment, with Catherine to renounce her title as Queen, and to become known as the Princess Dowager of Wales. Henry was now free to marry Anne Boleyn and make her his next Queen of England, a rather tenuous title in those days in Tudor England. Catherine remained a most devout Catholic until her death on the 7th. of January 1536.

Archbishop Thomas Cranmer who dissolved Henry the VIIIth's marriage to Catherine of Aragon Henry the VIIIth. and the Royal Navy.

Mary Rose, sunk in the Solent in 1545 with the loss of about 700 sailors,

In 1546 the Navy Board was established and made responsible under the Lord High Admiral for materials and the general civil administration of the Navy, it took until the next century for the Board of Admiralty to come into being through Charles the 1st. Elizabeth 1. The Church of England against the Church of Rome.

The Armada portrait of Queen Elizabeth 1 in 1588 But with the advent of Mary the 1st. to the throne of England, she very quickly took the country down the path of Catholicism, burning many so called heretics who refused to embrace her religion at the stake during her reign. She now died on the 16th. of November 1558, and now Elizabeth the 1st, was crowned the new Queen of England. Once more the country was given another religion, as the official religion became that of the Church of England. Philip the 11nd. of Spain was a standard bearer for the Roman Catholic faith, and one of his basic reasons ( no doubt urged on by the Pope in Rome ) for putting together both a large army and a huge armada of ships, was to invade England to restore the Catholic faith in that country.

King Philip II of Spain who sent off his Armada to conquer England in 1588 The Netherlands and a Spanish army. Philip contemplates the Enterprise of England. Philip now turned to the Duke of Parma for his thoughts, he suggested that 30,000 infantry, plus 4,000 cavalry might well do the job across the English Channel. All the Duke required to transport his proposed force was about 700 or 800 barges. He failed to add how they might make this crossing in safety without any intervention from Elizabeth's Navy. But Philip was awake to that problem, "Hardly possible!" he scrawled across Parma's plan. Philip now plans himself. The Pope urged Philip to get on with it all, the English Catholics pleaded with him to hurry, it could be that Philip only made haste slowly, he had once written,

In particular, the main item that weighed heavily upon Philip was the cost involved, he had begun to learn that Navies were even more expensive than were armies. But above every other consideration, he feared war with England especially! Drake at Cadiz Bay 29 April - 1 May 1587.

Sir Francis Drake Sir Francis virtually held a blank cheque to do mischief to the Spanish and their ships as he saw fit. It appeared to this swash bucking English sailor that there was a great opportunity to sink ships that Spain was preparing to invade his country. The Spanish galleys with their banks of oars and a deadly bronze ram, were no match for Drake's ships under sail, the well armed British ships simply outclassed any galley, it was no contest, as a galley under oars was never able to match a ship fitted with a broadside of heavier guns that could unleash a devastating amount of metal in a single broadside. The Spanish ships under Don Pedro were devastated, and something like 37 of his ships were destroyed, they included vessels under preparation for the Armada destined for the invasion of England. A 700 ton Levantor owned or chartered from Genoa was systematically pounded to pieces, her 40 bronze cannons all lost, as they went to the bottom of Cadiz Bay. Drake anchored his Squadron, and went about sorting out what prizes he wished to keep, what cargoes were worth retaining, and what ships he would put to the torch. Destruction of a magnificent galleon owned by the Marquis of Santa Cruz. The English Squadron becalmed.

The Duke of Medina Sidonia in charge of Armada Drake reports to Sir Francis Walsingham.

Of course the County of Sussex faced the channel, and it was here that Drake felt the Spanish might well strike. As Drake took his Squadron off towards Cape St. Vincent he knew that his main work against the Spanish Armada was still in front of him. The Siege of Sluys. 9th. June - 5th. of August 1587. However the defence of Sluys was really undermanned against the threat posed from Parma and his Spanish troops who were loitering in the vicinity of this important port. Any further incursion by the Spanish along the Flemish coast increased the danger to England. Parma made a move against Ostend, but the British garrison held firm, and he decided he must take Sluys. He laid siege to this port for almost three months over June/August 1587. A British fleet intended to come to Sluy's relief lay off the port, but too late, it was all over, The beard of the King of Spain may well have "Been singed by Drake at Cadiz." but here at Sluys, Parma had "Cut the arm off his enemy." Western Europe, Winter 1587 - 1588. Lisbon itself was a hotbed of foreigners and spies, but no one was really fooled, it was obvious that England and its Protestant Queen were the true target of all this flurry and preparation, it was just a matter of when would it all be launched? It was clear to Walsingham that his country was the target for a cross channel operation by Parma and his army, supported by a huge fleet from Spain. British and Dutch naval dispositions were planned accordingly, meantime all of Christendom was sitting, waiting to observe the outcome of this clash between England, mistress of the Channel and the challenger, Spain, aspiring to become the leading power at sea. Who would be the victor? Of course the case of Protestants versus the Roman Catholic faith was also very much one of the end results in question, the Pope in Rome was anxious for the right outcome. Merchants in Venice, Bankers in Europe, those frequenting the Parisian wine shops, all had their opinions, England, as she had for many years was the most formidable Naval force in the cold, rough waters of the Atlantic, she would be a tough nut for the Spaniards to crack. As for the invasion and conquering of a stoutly defended island such as England, it would be hard work. However, some would argue, Parma had a great record with his army, he had beaten many foes, whereas in England, their troops were largely untested, and their most likely leader, was the Earl of Leicester, and he was thought to have little military talent. If Philip was successful in England, then it was probable that the days of the Dutch would be numbered, as England was her ally. France would be in trouble too, the long shadow of Spain was cast across Europe at this time, and the outcome of the forthcoming clash of titans was awaited. Once Parma and his Army set foot on English soil, his task would be much easier than that he had faced in both Holland and Zeeland, so argued his supporters in Spain. But, the greatest problem Parma and his invaders faced would be the crossing of the Channel, and then the landings on English beaches. Of course many centuries later, this was the foremost task that Hitler pondered about for too long in the early days of WW2 until his opportunity had slipped from his grasp. How to conquer the skies above ( not a problem for Spain, as the potent flying machine was still to evolve as a weapon of war) and the waters below that formed the barrier between mainland Europe and England, the English Channel? To achieve his objective at sea, Philip of Spain was taking huge strides, he had drawn on the maritime resources of the Mediterranean, to his own Navy, he added that of Portugal, in strength, but second to Britain. Even the wily Venetians, who were not a bit enamoured at the thought of a Spanish victory, they put this on a par with any victory by the hated Turks, but still seemed prepared to put their money on the King of Spain being successful in his proposed invasion of England. Europe held its collective breath, and waited for winter to come to a close when the invasion period would become viable. Those like Drake and Raleigh were itching to gain the sight of Spanish sails, and to get on with this fight, they believed in themselves and their sailors, victory was all they would entertain. The sooner Philip brought on this battle the better. The stage was set, many living in Europe hoping for Spain to be defeated, their belief that a Spanish victory would also be a victory for the church in Rome, and the casting of that heavy shadow, they could well do without. As 1587 dragged to a close what would the new year bring? What dynasties may topple? Queen Elizabeth sat on her throne in the 30th. year of her reign, playing a tough game of politics, one hand of apparent friendship was shown to Spain as she tried to avoid war, the other hand held high a sword in readiness to descend if forced to let Drake off his tight leash at Plymouth. She also refused Hawkin's wish to blockade the Spanish coast , and her ships remained unmanned and without provisions. But preparations to guard against an invasion from the sea were continued, a system of beacons had been set up, ready to flash along the coast and inland to every county an early warning that the sails of an invading Spanish fleet were within sight. On land, England was far better prepared by April 1588 than she had been in the autumn of the previous year. All available ordnance had added to the seaward batteries in the seaport towns to help thwart any attack from the sea. Most Englishmen never thought it would come to a fight on their homeland, over many years they were conscious that they were guarded by the sea surrounding their Island, and had faith in their ships and sailors to continue their superiority over any intending invader. They really believed that their Elizabeth 1 would remain mistress of the most powerful Navy ever seen in Europe, its main strength being 18 powerful galleons, built for war. They were capable of both out fighting and out sailing any possible enemy ship afloat, each was over 300 tons. In turn they were backed up by 7 smaller galleons of 100 tons or more, plus fast pinnaces to scout, carry dispatches and be handy at inshore work. The scene in England. John Hawkins had long been responsible for the building and repairing of the Queen's ships. He had advocated increasing the length of her ships in proportion to their beam, to allow them both to sail closer to the wind, and for more guns to be mounted. The towering fighting tops featured in Navies both fore and aft, had long gone out of favour with the British. They preferred to mount heavier guns than to use the older boarding party assaults which were released from those fighting tops. Naval warfare had moved on, into another phase, and Hawkins had driven these changes, guns previously designed to kill enemy crew members, had been replaced with much more powerful and deadly ship destroying cannon. The British were the innovators, their guns now made of brass in lieu of iron, their ships of sleeker design, the Spanish had yet to take this route. In the west of the country at Plymouth, Sir Francis Drake had his western squadron of ships, careened and brought to battle readiness, whilst at Chatham, this squadron was likewise prepared. The Lord High Admiral was Lord Howard of Effingham, Earl of Nottingham, although well past fifty years of age, like Drake, he was chaffing at the bit, ready to take on the Spanish, his flag flew in Ark Royal.

Lord Howard of Effingham, Earl of Nottingham. It is difficult to decide if Elizabeth was right to keep her ships ready, but in check, awaiting the Spanish move, or if, as Hawkins wanted to do, she should have let them blockade the enemy in their home ports. If the latter option had been decided, the Queen's fleet may well have spent themselves needlessly off Spain, and have been much less ready for the final battle. As always, hindsight makes it all much easier to read and decide, but it does seem from this distance that Elizabeth's prudence was the right course to take at that time. Her ships, at their peak and ready to attack and be victorious at the very right moment. Meanwhile at Cadiz in early 1588.

The King had set a deadline for a sortie at not later than the 15th. of February, and sent off to Lisbon, the Count of Fuentes to see that Santa Cruz set off, all to no avail. The Marquis had been assured he was fighting in God's cause, but had not been moved by such exhortations, he was aware of too many fights against the Turks to gain any confidence from that area. He had wanted an overwhelming majority of at least 50 galleons to beat the English, he had but 13. All the other ships he wanted in large numbers were not forthcoming, he seemed resigned to the fact that this time, he could no longer stall any more. He just had to sail, now with his sailing date less than a week off, he went to bed, and died. It did not take Philip11 long to select his replacement, the day he had the news of the death of the Marquis, he appointed Don Alonso de Guzman el Bueno, Duke of Medina Sidonia and Captain General of Andalusia, his Captain General of the Ocean Sea. It had been but the year before when the Duke's timely arrival as head of the local militia at Cadiz had been gived the credit from saving that port from its sacking by that British pirate Drake. He was also a very devout son of the Catholic Church. He was a man of medium height, having small bones, and a sensitive face, but did not ooze with life, in fact he does not have the appearance of being a lucky man, and that he would most certainly want to be on this mission to defeat the English in their own back yard of the English Channel. He really did not want the King's appointment, he dashed off a letter begging to be relieved, citing the fact he always was seasick, he always caught cold. No doubt if the British had been privy to all these shared doubts, they would immediately take heart at at this new appointment in Spain. He seemed to be defeated even before his ships set sail. The King pressed his new appointee to get on with it, and he set off for Lisbon. On arrival he was shocked at the chaos with which he was confronted, some ships had more guns than they could use, others had none, some were laiden too deep to threaten their safety, others not loaded at all. Since his predessor's death, the fleet was in limbo. Medina Sidonia needed to use his authority, and sort it all out, the private secretary to Santa Cruz was making off with all the plans for battle, the intelligence reports, admin files before the new Captain General could even see them. He appealed to the King, and at least had the chance to peruse them all, he also had to gather to him some semblance of a personal staff. Santa Cruz had asked for more heavy guns to be provided before his untimely death, these had been promised, but were difficult to manufacture, and not too many had the expertise to cast them, most of the good gun casters were in England. The new commander was not happy with the number of galleons at his disposal, about 8 of them about 400 tons apiece, the Portuguese had some 12 galleons, but one had been lost when Drake threatened earlier, another too leaky was beached and broke up, Santa Cruz on inspecting the ten he found several wanted serious repairs, and one too small and altogether too old. All in all a dismal picture, but he had found Florencia, a new and powerful battleship, with some galleons from the Indian guard, Medonia Sidonia had about 20 galleons, about equal to the Queen's 20 best ships The Armada Sails. Medina Sidonia had steeled himself for his coming ordeal, and was now anxious to make a start, his ships as ready as they were ever likely to be. His first line was made up of two squadrons of Galleons, those of Portugal, and those of Castille, his Chief of Staff, Diego Flores de Valdes, sailed in San Martin, flagship of the Captain General. The second line, comprised four squadrons, each of ten ships, were large merchantmen, some, heavily armed, in addition, thirty four light and fast ships for dispatch carrying, and scouting duties were spread out about the fleet. Some attached to the fighting squadrons, whilst one group kept together to act as a screen. Finally, an ugly squadron of twenty three freighters and supply ships, who could certainly not look after themselves, made up the total fleet of one hundred and thirty ships both great and small. Medina Sidonia had drawn up a very comprehensive list of his Armada, the order of battle by squadrons, the name of each ship, the number of guns, its sailors, and its soldiers. Amazingly, this listed the priests, and friars on board, one hundred and eighty of them, the field guns, even the number of cannon balls, and all the provisions loaded were on this list. This Armada was called Le Invencible or in English, The Invincible. Not only was this list drawn up, but it was published only ten days after it had been produced, with the fleet still anchored. Now two weeks later a second copy was published at Madrid with official corrections, no doubt English spies had been hard at work in Spain trying to glean snippets about the Armada to send home. But here on a platter was the whole story, it went to Rome, to Paris to Cologne, and copies might be bought in Amsterdam. The English Captains could well have taken into action the whole details of their opposition, perhaps this formidible list was meant to cast fear and trembling into the English foe, the Spanish must have thought their propaganda would do some good. Experienced pilots were spread between the squadrons, who knew the English Channel and the North Sea, detailed Sailing Instructions from the Scilly Isles to Dover had been distributed, the Captain General was ready, and now a holy Friar assured him "That God would assure Spain Victory!" His cup must surely have runneth over. On the 28th. of May 1588, San Martin led the Armada out to sea, it was not until the 30th. that all the ships had cleared port. The fleet kept together, but Medina Sidonia soon learned the lesson that all Convoy Commodore's from WW1 and then WW2, had long discovered, that the Speed of the Convoy is indeed governed by the speed of the slowest ship in the convoy. Many of the supply ships proved to be cranky and sluggish sailers, beating up the Spanish coast was slow and weary work, it took the Fleet, 13 days to sail but 160 sea miles from the Rock of Lisbon to Cape Finisterre. When the fleet lay for three weeks locked in by the bad weather, a good deal of the food on board was consumed, and arrangements had been made to augment the food supply by meeting victualling vessels off Finisterre, for four days the Fleet hovered here, many ships reporting an alarming shortage of fresh water, many water casks proving to be defective, and when broached, the water therein, being both green and stinking. It was decided the Fleet must put into Corunna to gather what provisions they could, but above all to replenish the water. So, only 20 days out of Lisbon, on Sunday the 19th. of June about 50 of the ships were at anchor. The rest of the fleet including the slow supply ships stood out to sea. A Howling Gale. A Letter to the King. And Parma was but at half the strength he had been in 1587, should not his Majesty sue for peace with England, and defer this invasion for another year? Philip's reply was fast and firm, " You are to sail at the first opportunity." A Council of War.

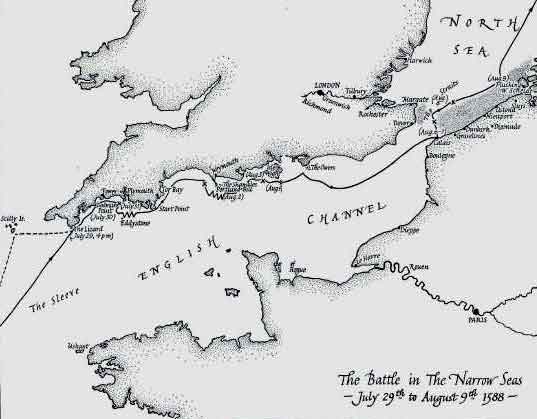

The vote was No 3 alternative, stay here and wait for all the stragglers to rejoin the Fleet at Corunna. It took a month after the dreadful storm before the Fleet was ready to sail once more. Thus two months had elapsed since the Armada had first put to sea from Lisbon, it was the 21st. of July, virtually two months wasted, but a brisk south wind filled the sails as the Fleet at last swept on towards England. The Scene in England. Drake was anxious to be away, he wanted to stop the Spanish long before they reached the shores of England, he believed very much in his own ability as a sailor, and a tactician, he was also quite zealous about his religion, opposed as it was to that of Philip11 of Spain. Notwithstanding Drake's wishes to take on the Spanish fleet on its own doorstep, the gales that obtained at that time would most likely have precluded him from even reaching the shores of Spain, and his ships would have suffered severe damage to their detriment. It seems his Queen's judgement in holding Drake and his ships back in reserve was vindicated. At the time before his untimely death, Medina Sidonia had been ordered by his King not to be put off by an English offensive close to home, he was to press on, meet up with Parma, and get on with the task of invasion. Drake may well have missed the opposition if he had gone off seeking them, the door would then have been well and truly left wide open. Drake has to be content being named as Vice Admiral to Howard. Intelligence brings news of the Armada. The Queens ships had proved to be well found, and coped with the bad weather, not so, some of the merchantmen, they were leaking, and required spars and new cordage. Some vessels were short of food, but more importantly of water too, these problems were attended to with some urgency. The Spanish Armada is sighted near the Scilly Isles. At about 1500 ( 3PM ) the incoming tide at Plymouth was in full flood, that coupled with a fresh South West wind meant the English ships would need to at least wait until the next tidal ebb, due about 2200 ( 10 PM ) that night, before they could go to sea. The large Royal Galleons and the better armed merchant ships commenced their warping out of Plymouth Sound, the next morning, Howard led his ships beating out to sea, the dice had been rolled, the game was about to commence. It was after Fleming had delivered his warning about the Spanish ships that Drake was reputed to have made his famous remarks:

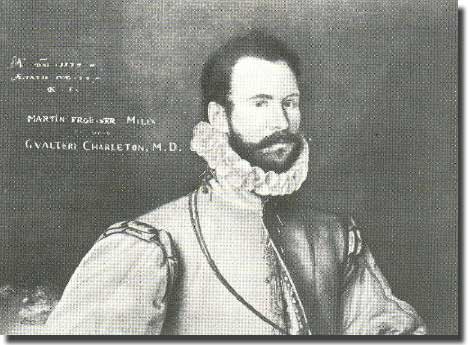

But did he in fact utter that phrase? It certainly is within the compass of what Drake was like, cocky, very sure of himself and his abilities. There does not seem to be any contemporary record of this legend, but it makes good reading, even in the twenty first Century. 30th.July-31st.July 1588. Now, with his fleet at one, Medona Sidonia, held a Council of War, what to do? It seemed the Spanish Commander led by consensus, rather than taking a decision and then issuing orders to carry it out. Some of his leaders favoured an attack on Plymouth, but eventually it was decided that the entrance to this port was too narrow, and shore batteries would be dangerous. It seemed that the only decision agreed upon was that the Armada would sail no further than the Isle of Wight until a rendezvous with Parma had been organised. The Armada now started its move up the Channel, in the van, the Levant Squadron, the Duke with the main group of Galleons, on each wing followed the Guipuzcoans and the Andalusians, safely cosseted in the centre, the hulks or supply ships, with Recalde and his Biscayans with the remainder of the Galleons bringing up the rear. When passing the Lizzard, an English pinnace sighted the force, firing a small cannon before taking off, no doubt to spread the word, the Spanish are under way. By late afternoon all this force anchored in the lee of Dodman point, and some scouting pinnaces were despatched to gather what intelligence they could find. The British were beyond the Eddystone light, from their shrouds the topmen could make out the vastness of the Spanish fleet, probably the greatest number of hostile ships of war ever viewed by English eyes. No doubt both sides bedded down for the night wondering what the morning held in store for them. In those days of sail, the weather and its wind held the key for defeat or for victory, whoever harnessed the elements better, and fought their ships with more vigour and efficiency would win the fight. On the evening of the 30th. of July, the prevailing wind was West-South -West, the Spanish were to windward of their foe, holding the weather- guage. Come the next morning, the wind had moved to West-North-West, coming off the land, by day break, the Spanish ships still held a windward position, and a British Squadron was trying to work around to get ahead of them to the West. Now cannon shot was exchanged with the Spanish van. But to his horror, Medina Sidonia suddenly sighted the main elements of the English Fleet, and they were behind his forces, directly to windward, some how they had gained the weather guage, and for the next 9 days the wind would blow in the main from the West. He would never ever regain the advantage of the wind, Howard and Drake had somehow out manouvered the Spanish Commander. It seems that the English stood well out to sea, and then close hauled, sailed back and around the sea ward side of the Armada's wing, meantime the Spaniards had sailed or even drifted some miles to the east. Hawkins work in ensuring the British ships could sail closer to the wind, had with little doubt, been the reason that Howard and Drake found themselves in a commanding position, the wind in their favour. The Captain General fired a signal gun ordering the Spanish ships to form into battle order, they now took up a crescent formation, and sailed with precision and skill to maintain great defensive strength. The English had never witnessed such a sight before, if they wanted to retain the weather guage, they could only attack the wings of the crescent, here the Spanish placed their strongest ships. If the English were rash enough to pass the extended horns of the crescent, they would be chopped up by the Galleons, which would also hold the wind over them. On the other hand, any damaged Spanish ship could seek protection in the centre of the crescent. We almost have a stale mate situation here, the British hold the wind advantage, but the Spanish crescent formation is almost impregnable. The Battle commences, Howard and Drake versus the Spanish Armada. carry his challenge to the Spanish Admiral. The niceties over, Howard at 0900 ( 9 AM ) on the morning of the 31t. of July led his fleet in line ahead against the northern segment of the Spanish crescent, which happened to be closest to the shores of England. This end of the Spanish ships were mainly drawn from de Leiva's Levant Squadron, and the last ship was Rata Coronada, as Howard in Ark Royal was crossing her stern, her helm was put down, bringing her broadside to broadside and steering a parallel course with Ark Royal. Broadsides were exchanged, Howard thought he was engaging the Spanish flagship, although the Spanish ship tried to close the range she could not magage it, and the two lines of ships were kept far enough apart that no damage was really inflicted by either side. Meantime, a group of the English ships led by Drake in Revenge, Hawkins in Victory and Frobisher in Triumph fell on the Spanish rearguard, commanded by the Vice Admiral, Juan Martinez Recalde. The Spaniard sailed round to face the attack, his San Juan de Portugal, was

Frobisher The three English ships closed the range to about three hundred yards, and pounded the San Juan for an hour, she could not get at her tormentors, when at last the huge Grangrin, came back with the rest of the Biscayans and drove off the British ships. San Juan was shepherded back into the centre of the Armada to lick her wounds. The English ships now moved away to end any fighting on day one. Now Medina Sidonia tried to regain a windward position, he gave up his defensive crescent formation, formed up his ships in line ahead, for an attack in Squadron columns, as they sailed off close hauled, a fine sight, but Howard was able to maintain whatever distance he pleased, whenever the Spanish tried to make a dash towards him. The odd salvo from the British ships kept the Spaniards at arms length, after three hours of toing and froing, the Spanish Admiral gave up, and turned away. His official log read:

I believe the English were some what suprised, the Spanish were proving to be both bigger and tougher than anticipated, they had displayed a fine discipline and their seamanship was good, they would need to be kept at a distance so that their shorter range guns in some quantity could not be allowed to wreak their havoc. The only saving grace in a frustrating day for the British, was the fact that the Armada had now swept past Plymouth, and that port was at least safe. But now the Armada was sailing on quite majestically up the channel, no doubt seeking a rendevous with Parma and his invading army, Howard and his cohorts need to do much better and soon. The real damage to the Armada was self inflicted, when reforming into the defensive crescent, Pedro de Valdes's flag Nuestra Senora del Rosario collided with another Andalusian vessel and lost her bowsprit. Then came a tremendous explosion, San Salvador, was ablaze on her poop and two decks of her stern castle had gone, gun powder stored in her stern had blown up. The ship was towed within the safety of the hulks or supply ships. Rosario now lost her foremast, she was taken under tow, but the cable parted. Medina Sidonia was advised to proceed with the fleet as it was growing dark, he agonised about abandoning Rosario, but in the end ordered the fleet to sail on. This was his first failure, no matter what advice he was given and acted upon, he alone would shoulder any subsequent blame that was apportioned. Now Howard sought advice, by gaining the windward position, he was no longer in front of, He selected the veteran Drake to lead the fleet in Revenge, to seaward sailed a privateer Margaret and John, from London, of 200 tons and mounting 14 battery guns, a nippy ship, she was in fact well in the van, when she came upon a large Spanish ship obviously in trouble, her bowsprit and foremast gone, a galleass and pinnace standing by her. The latter two ships immediately took off leaving Rosario to her fate. Rosario seemed deserted, no sails drawing, no lights visible, Margaret and John nudged in closer, and set off a volley of musketry, several large guns answered in reponse. This caused the privateer to move away, and set off a broadside, she now stood by until midnight, Howard hearing gunfire sent a pinnace to order Margaret and John rejoin. Rosario was to be ignored, it was mandatory to keep the English fleet as one, if the Spaniards anchored in Tor Bay, Howard would need every ship in his command to take them on. The wind had calmed down after the squall causing Rosario's problems, visibility was poor, With very little moon, and Ark Royal following Revenge, in fact lost sight of her lantern. It was again in sight some distance away, and more sail needed to be set to catch up. As a watchkeeper in the Royal Australian Navy in WW2, I know how difficult it was with 80,000 horse power available to me to maintain station at night, I can well believe how much tougher it was for an Officer of the Watch in 1588 to keep in station on Revenge. An Admiral then, would have been no different to one in my time, they hate you to be out of station, it was then I am sure, as it still is today, " A Given" just Stay in Station under any condition, and no excuses are accepted. When the first fingers of light heralding a new day crept over the horizon, to Howard's absolute horror he found the lantern he was following, did not belong to Drake's ship, but to that of the Spanish flagship. He had the Bear and Mary Rose with him, all the rest of his command were miles away, only their topmasts in view. He had almost become embraced within the arms of the Spanish crescent. It seems that the Spanish Admiral let slip the chance to despatch three of the English fleet, with their Commander among them. Howard and his two consorts quickly went about and made themselves scarce, and watched the Armada continue slowly up the channel, ignoring Torbay, by afternoon the rest of the English Fleet had met up with their leader, who must have been very red faced with his monumental and nearly disastrous error. Drake reported what he had been up to overnight, he had observed shadows of ships passing to seaward, lest they be the enemy trying to slip some vessels past to gain the weather guage, he turned to challenge them, extinguishing his lantern at the stern, so he would not mislead the rest of the fleet. It was not enemy ships, but a group of innocent German merchant ships. He now ran into Rosario, captured her and then under escort of Roebuck sent this prize into Torbay. Don Pedro de Valdes who had been taken prisoner, was now presented to Howard by Drake. No excuse was offered by Drake, no one else managed to sight the reported German ships; was Drake merely covering himself in a tricky situation? We really do not know the answer to that, and no record of Howard censuring his conduct seems to have been recorded. Once again the flambuoyant Sir Francis had achieved success, and the spoils of a fine prize were added. It does seem that the Spanish gave up a fine ship very easily, Rosario was disabled by her collision and losing her bowsprit, then her foremast, little effort in rigging a jury mast seems to have occured, then Drake captured the vessel without any fight from the Spanish. This one episode does not auger well for the Armada as a whole. Not only was a 46 gun ship lost to the Spanish cause, in the Captain's cabin, were 55,000 gold ducats. A Second Prize also picked up on the 1st. of August. Several centuries later, I lived here at Weymouth for almost a year, when undergoing the anti-submarine segment of my course as a Specialist Torpedo Anti Submarine Officer. It was taken at HMS Osprey, the Anti-Submarine training school at Portland, a few miles from Weymouth. On that Monday, on the first day of August, the wind dropped right away, the Spanish reorganised their grouping, all the fighting ships were split into two parts, the more powerful were placed as a rear guard, a smaller group were sent off to guard the van. The next morning, the calm gone, a fresh breeze now coming from the east, giving the Spanish the weather advantage. A Running Fight without result. The enemy rear guard saw the problem and sailed an intercepting course, bringing both columns within musket range, now a running fight took place. Howard continuing to try and round the Spanish rear, whilst in turn they tried to board English ships. Neither side was successful, the wind from the south east pushing both fleets towards Lyme Bay. Off Portland Bill. This group were under attack by four Spanish galleasses, sent in by Medina Sidonia to grab this seeming opportunity to sink them. But the tide was ebbing, and the current was pushing the Spaniards aside, this specific area is renowned for the boiling race which prevails as the tide races out at about 4 knots. In fact Frobisher was in a good position, Howard, with the wind now veering to the south was able to lead some of the Queen's galleons and the larger volunteers off to rescue Triumph, whether she, and her other ships, were in fact in need of rescue is a moot point. But Medina Sidonia saw what Howard was about to do, and led his vanguard of 16 ships to stop the English ships from their rescue mission. Before contact could be made, the Spanish Admiral saw that Recalde in his repaired San Juan had been cut off, and was surrounded by some twelve ships, he sailed San Martin to the rescue. As Howard began to pass by in Ark Royal, the Spaniard struck his top sails thereby inviting the Englishman to come alongside, use his grappling hooks, and then board for a hand to hand fight. But a broadside from the Ark resulted, with Howard effectively saying "No thank you for your invitation." As each English ship passed in line ahead, they too loosed off a broadside, they went about, and on the return pass fired off a second dose. The English ships harrying San Juan, now closed in around San Martin, and for an hour she stood alone returning fire, but taking a lot of punishment. A line of Spanish galleons now came up to succour the Spanish flagship, and the English withdrew, the Armada reformed and continued up the channel. For Medina Sidonia, it seemed that when he held the weather guage even briefly, he was unable to grapple and board, here he felt he would hold an advantage over his opposition. But, the English ships were fast enough and weatherly enough, to choose what distance they desired, and, their heavier guns in greater number, reinforced their desire to keep their distance, and not be enticed to fight in close with swords and pikes. As a last straw, the English gunners were better and could fire their weapons much faster, he was indeed in a bind. Howard too had his concerns, he had anticipated that his gunners would sink a number of the Spanish fleet at his first skirmish, or at least cripple ships, causing them to fall out of formation, allowing them then to be destroyed. This had not come to pass, only two prizes had been taken caused in the main through sailing accidents, although gun fire could have contributed to their capture. Howard had a huge worry, many ships had fired off most of their shot, he also needed more powder. The Channel Pursuit Continues. 2/6 August. 1588. Medina Sidonia had time to send off messages to Parma, exhorting him to be ready to embark his troops at short notice, and inviting him to come and join in an attack on the following English ships. At dawn on Wednesday the 3rd. of August, Gran Grifon was seen to be dropping behind the main body of the Armada, Recalde led a line of his first line ships to assist her. It was probably Drake in Revenge who sailing past the errant Spaniard gave her a broadside, came about and gave her a second, then crossing her stern close enough to rake her with musket shot. Other English ships joined in, and the bulk of the Spanish right rear was engaged, Gran Grifon was in trouble, a galleass managed to take her under tow, and get her into the safe arms of the fleet. Sixty Spanish sailors died and another seventy were wounded, but the Armada continued its stately march up the channel. By the afternoon the wind fell away completely, the two fleets were drifting only a mile apart, the occasional wind puff brought Howard relief in pinnaces, and harbour craft loaded with stores of powder and shot. On each occasion of a close encounter the Spanish had been able to rescue their badly damaged ships. A new strategy was needed for the English forces, and after consultation with his Captains, Howard divided up his 100 ships into four about equal Squadrons, command went to: Drake, Hawkins, Frobisher and lastly to himself.

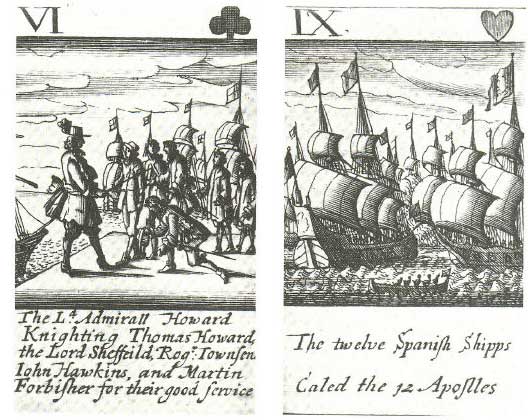

Howard knights both Hawkins and Frobisher. Bottom right, twelve Spanish ships. On Thursday morning the new set up had its first chance to perform, Hawkins saw two Spanish stragglers, the royal galleon San Luis de Portugal and a West India merchant ship Santa Ana. As there was no wind, Hawkins had his boats tow the fighting ships towards the enemy, with Victory in the lead. Medina Sidonia saw the problem and sent off three gallasses to the rescue, for good measure and support the great carrick La Rita Coronade was towed with them. Now it was the turn of Hawkins and his group to come under threat, but Ark Royal and Golden Lion were towed to the scene in support of John Hawkins. The two groups stood off pounding away at each other, and the remainder of the Fleet looked on rather like spectators at a football or cricket match might do today. One of the galleasses was damaged taking on a list, another lost her lantern, the third her figurehead, although Howard claimed they never again appeared in batlle, they were towed within the bosom of the Armada without apparently suffering any lasting damage, it seems that Howard may well have been over estimating the damage he caused to the Spanish ships. It has been a habit with fighting men over the centuries to claim losses and damage to the enemy in a greater proportion to that which in fact was achieved. On both the German and British sides, the Battle of Britain is a case in point, some quite incredible claims of the number of enemy aircraft shot down appeared on both sides of the English Channel. The breeze freshened, two actions each independent now came about, three English Squadrons were attacking the Spanish rear, whilst the fourth English Squadron was being struck by Medina Sidonia's van. Both fleets were close to the southern end of the Isle of Wight, and near the Solent's eastern entrance. Prior the the despatch of the Armada from Spain, King Philip was prone to offer his Admiral advice on any number of subjects, the suitability of the Solent as a safe anchorage for the Spanish Fleet, should it have to sit and wait for Parma and his Army to get ready, was one such area he addressed. But to achieve this safe anchorage, Medina Sidonia thought that he must first seize the Isle of Wight, a difficult task with Howard and his ships close by. This possibility was also in the forefront of Howard's mind, and this caused him to want to maintain an inshore position over his foe. At one stage, the Triumph was in danger of being caught alone with but little wind, 11 launches had her under tow, then two of the largest English galleons, Bear and Elizabeth Jonas came to deter the Spanish attack, along came the wind, Triumph shook out her sails, and was up and away. Drake was continuing his attack, slowly forcing the Spanish to the east, and northwards, shoal water was close under the Duke's lee, but he saw the danger in time, another 20 minutes or so would have found the Armada stranded on the rocks, Drake was foiled. A gun alerted the Spanish to their peril, on went more sail, and they stood away from danger to the south-south-east. The English followed, again, no knock out blow had been achieved, shot and its shortage was again a problem for Howard, also he wanted to rendezvous with reinforcements in the form of the eastern Squadron under Seymour off Dover. He needed to bring the Spanish to battle, and he needed a victory, and above all he needed it sooner than later. When calm reigned on Friday morning, Howard saw fit to knight both Hawkins and Frobisher for their service. No word had been heard from Parma, and the Duke was desperately short of shot for his galleons, whilst Howard faced the same shortage, at least he could replenish as he sailed along the southern coast of his homeland, an urgent appeal for help went off to Parma. Both Admirals thought they had inflicted severe damage on their respective enemies, but this supposed damage was probably overrated by both sides. Any Captain was loath to report the full extent of deaths in his ship, he hoped to continue to draw pay for any dead men who were still retained on the muster list of his vessel. The other problem with gunnery in those times was distance from one's enemy, although the British carried heavier guns which they thought could be used at a greater range from the Spanish ships, the further away they were fired the more inaccurate became the shot. Any error was compounded by extending the range at which guns were fired, the most devastating effect of superior guns was still obtained at close range, and this lesson had yet to be learned by the British. The Spanish had another problem, they would soon be beyond the relatively confined waters of the Channel, the more open reaches of the North Sea beckoned, on that Saturday afternoon near the Calais Roads, sails were struck, and the signal to anchor was made, no sooner did the cables run out, than the English fleet followed suit. Both fleets were anchored within gunshot of each other, now Seymour with a further 35 ships joined Howard to anchor close by. Justin of Nassau had indicated his Dutch ships would take care of Parma once they were on their way in flat bottomed boats, but the English were wary of the wily Dutch, and Seymour had kept his own watch cruising off the Flanders coast. Now Seymour had joined Howard, the Dutch took on the job and Justin was ready to take on Parma should he venture into the Straits of Dover with his invading army. But Howard was unaware that the the Dutch were on watch, and he was still fearful about both the Armada and the invading component of Parma poised to move on his beloved England. For the Dutch ships, word was about of movement in Parma's camp, perhaps the waiting period was about to end. Both Fleets Anchored off Calais. At first it was decided to send Sir Henry Palmer off to Dover in a pinnace to gather up fire ships and suitable combustibles, but that would delay an attack, with favourable South-South-East winds conjoined with high spring tides, Sunday night was the right moment, no time to go off to Dover, the time to strike was nigh. Drake offered Thomas, a 200 ton Plymouth ship, Hawkins listed one of his ships, then as the thought of the use of fire ships now, took hold, a further six ships were earmarked for such a role. These vessels were hastily prepared, useful stores removed, but the guns were double shotted to hopefully fire and add to the terror when fire made them hot enough. What Howard could not know was that Gourdan had counselled the Duke that his anchorage was both exposed and dangerous, and he was essentially remaining neutral, but the Armada could purchase what fresh food they could ashore. Medina Sidonia had told Parma:

Fly boats were fast, little ships of war with a shallow draft, but Parma had not only none to spare, he had but a few of them. The invasion fleet he had prepared at Dunkirk and Nieuport, were but canal boats, no masts, no sails, and no guns, but on the eve of a British attack of which the Duke had no idea, he was also ignorant of the fact that Parma was in no way able to come to his assistance. On Sunday morning Medina Sidonio had news from Parma at last, Don Rodrigo Tello's pinnace arrived, he had seen Parma at Bruges, his message, he would be ready in six days, but on leaving Dunkirk only the night before, there had been little sign of Parma and his troops arriving there, Don Rodrigo said he believed it to be at least a fortnight before the invasion force was ready to depart. In fact, it was Monday the 8th. before Parma left Bruges, and even on Tuesday at Dunkirk the attempt at manning the flat bottom boats by his troops had an air of unreality about it. Back at Calais. The Duke took what precautions he could in anticipation of a fire ship attack, he ordered a screen of pinnaces and ship's boats to be fitted with grapnels, they were to grab any fire ship, tow it out to sea clear of his fleet. Ships were to avoid any fire ships that got past the screen by slipping and buoying their cable, stand off out to sea until the danger had past, return to pick up their cable and anchor again. Up to midnight all remained calm, the wind was rising, now at the edge of the British Fleet, were eight fires, all moving rapidly towards the Spanish ships, driven by the wind and incoming tide. The screen of pinnaces was closing in, but the fire ships maintained a tight line, two fire ships were caught by a pair of pinnaces, but as the next pair went to work, the double shotted guns, now sufficiently heated, started to fire off their deadly load. The pinnaces were sufficiently distracted to allow the six fire ships to sweep past them, Medina Sidonia fired a gun, slipped his cable and stood out to sea. But his ships did not follow, panic swept the Spanish anchorage, many Captains cut their cable to flee before the supposed Hell-burners, they ran in total disorder before the wind, the strong set of the current, plus the rising gale swept the ships out through the straits and onwards towards the Flemish coast and its sandbanks. The Spanish order which had been so admirably maintained, now at last, broken. The Duke in San Martin sailed a quick leg out to sea then returned to drop his sheet anchor a mile or so north of his original anchorage. Four of the Spanish royal galleons were all close by. With the first light, they were all of the Armada in sight, with the exception of San Lorenzo, de Moncada's leader of the galleasses, she had caught up someone's cable in her rudder, and in a night collision her mainmast was not functioning properly, she was inshore barely making progress. The bare bones of the six fire ships that had caused all the panic were still smouldering close to the Calais pier. A dismal sight for Medina Sidonia. Daybreak over the English Anchorage. During the night Howard had not been able to assess the success or otherwise of his fire ships, now he could see the Spaniards had scattered, and he sent his other Squadrons off to deal with the only vessels in sight, to Sir Francis Drake was given the honour of leading this charge. Howard's ships would take care of San Lorenzo, which was desperately trying to gain the sanctity of Calais Harbour, but a fast ebbing tide stranded her, hard aground under the walls of Calais Castle. Here was a problem for Howard, his ships drew more water than those of Spain, he could not close in to destroy the stricken Spaniard with gunfire, he sent off boarding parties in ship's boats, their task very difficult, as the huge galleass was heeled over towards the shoreline, her steep sides hard to climb. A brisk fight ensued until de Moncada was shot in the head with a musket ball, and resistence collapsed, the ship was sacked. The Governor of Calais claimed the vessel and her guns for himself, and only his threat to fire on the English boats surrounding the wreck persuaded the sailors to withdraw. Howard recovered his boats and their crews and went off in the direction of gunfire. A Running Fight in the North Sea. San Martin was mangled, and San Mateo likewise, the Spanish sailors' slaughtered, ships were isolated, and his fleet was being crowded towards the Flemish sand banks. This battle had raged since just after sunrise, there seemed enough time before the sun set for Howard and his ships to complete the rout of the Armada. But, a blinding rain storm with squally winds gave the Armada a reprieve, the British ships had to keep out of each other's way, for some 15 minutes, Spanish ships and their total destruction was forgotten. Just enough time for Medina Sidonia to reform, shorten sail, and be just out of range, they lived to fight again. The British take stock. Howard wrote to Walsingham:

He went on to say he would need victuals too, and then gave a brief report of the day's events.

Drake had summed it all up thus:

Drake's post script very much to the point:

On the Spanish Side. The squall had seen the great Biscayan Maria Juan sink, San Mateo and San Felipe, leaking so badly, their time up, they were put aground between Nieuport and Ostend. The fly-boats of Justin of Nassau soon grabbed them both. One of Diego Flore's armed merchantmen sank. The Chase continues. The wind had dropped somewhat and gone round to the north-west, the Spanish sailing as close hauled at possible were fighting to gain more sea room, the changed colour of the sea showed the depth of water was falling, soon the Armada would be stranded on the sands of Zeeland. Medina lay to, and waited for the enemy, but the English stood off, they knew the risks of sailing in any closer. Even when laying to, both wind and current were edging the Spanish to leeward, anchors could not be expected to hold in this loose and shifting sand. Pilots in the Spanish ships counselled there was nothing else to do but to try and edge to seaward, San Martin drew 5 fathoms, the leadsman called 7 fathoms, then 6, disaster about to happen. It was suprising the ships had not grounded, the British waiting for the elements to achieve what they had not, the utter destruction of their enemy the Spanish Armada. Now a miracle for Spain, the wind backed, right round to the south-east. The whole fleet was suddenly able to stand away into deeper water, the dreaded sand banks some how avoided, the Duke,and his Chaplain felt that the fleet had been aided by a miracle of God. Throughout the Armada's progress from their first sight of the British fleet, and their progress up the channel, off Calais, and now, the weather had favoured them, far more than they had any right to expect. Howard was disappointed by the turn of events, he had been in a ringside seat, about to see his Queen's enemy totally destroyed, at the very last minute, this total victory was denied to him. Hoping that both ammunition and food would soon arrive, Howard continued to tag along behind the Spanish ships, he would follow as far as needed to ensure England and Scotland remained safe. Seymour was to be sent back with his Squadron to the Downs, to ensure Parma did not attempt to cross with his forces. Seymour protested, he wanted to be in at the death, even accusing Howard of wishing to hog all the glory. He protesteth in vain, the Lord Admiral meant to maintain his ships between the enemy and the shores of England. The Spanish Decide. The wind held on, both fleets past Hull, then Berwick, on the fourth day Friday the 12th. of August close to latitude 56 degrees North, the English turned away, and made for the Firth of Forth in Scotland. Medina Sidonia watched the British sails drop astern, he had survived, but he knew this was defeat, he had failed in his mission. The British Fleet goes home. The Queen goes off to Tilbury to inspect her Army. At the end of the review the Queen had spoken to her people:

The shout of applause was tremendous. The Fleet is home, but not to an enthusiastic welcome.

The Queen returned to St James. There could be no let up, the Fleet must stay in readiness, and the Army at Tilbury be kept on the alert. Would Parma make an attempt to invade, would the Armada come again to back him? For the moment any threat was over. The Armada limps home. Medina Sidonia had not sought his command, he had pleaded with his King to relieve him prior to the departure of the Armada, he was sent on his way. He carried out a difficult command to the best of his ability, now he just wanted to go home back to his orange groves. King Philip11 relieved his Admiral from his command, excused him from reporting to the court to kiss His Majesty's hand, and allowed the Duke to at last seek peace amongst his oranges. History and Howard.

Acknowledgement. It is of interest that The Folio Society of London, has republished this book, to be once more available to those who enjoy their history of the sea, and one of the great stories from long ago.

Chart of Battles between Armada and English ships. |