|

A History of Submarine USS Searaven who rescued 33 Royal Australian Airforce personnel from enemy held Timor in April 1942

USS Searaven. History for U.S.S. Searaven WW2. Patrols

Searaven was laid down on 9 August 1938 by the Portsmouth (N.H.) Navy Yard; launched on 21 June 1939, sponsored by Mrs. Cyrus W. Cole; and commissioned on 2 October 1939, Lt. Thomas G. Reamy in command. In the two years preceding America's entry into World War II, Searaven operated in Philippine waters conducting training and maneuvers. At the outbreak of war between the United States and the Japanese Empire, the submarine was at the Cavite Navy Yard in Manila Bay. During her first two war patrols in December of 1941 and the spring of 1942, she ran supplies to the American and Filippino troops besieged on the Bataan Peninsula and Corregidor Island. In a night action in the Molucca Strait on 3 February 1942, she torpedoed a Japanese destroyer and claimed her first victim of the war. Searaven conducted her third war patrol in the vicinity of Timor Island of the Netherlands East Indies, from 2 to 25 April 1942. On the 18t./19th. she rescued 33 Royal Australian Air Force men from enemy held Timor. Escape from Timor Parties of displaced Australian servicemen were dodging the Japanese in South-East Asia, seeking any means of escape to Australia. Aircraftsman L. Bourke was one of a rearguard of 33 RAAF officers and airmen who remained behind on the island of Timor when the Japanese overran the Netherlands East Indies. He related that 'the mission of his party was to carry out rearguard and destructive operations in order to deny the Japanese the use of airfield and ground installations in Timor'. The officer in charge of the group was Flight-Lieutenant Bryan Rofe (D.Met.S.) formerly OIC of the meteorological section at Koepang. The subsequent adventures of this party constitute what may be one of the most graphic and dramatic escapes in Australian war history. 'It was a story of sheer courage and of grim hide-and-seek with the Japanese in the jungles and hills of Timor', reports a staff writer of T.V. Times. The events leading up to the escape were described mainly by Rofe himself to the T.V. Times. 'It all started even before Japan entered the war. Members of 2 Squadron RAAF were sent to Timor where, living as civilians, our job was to establish relations with the Dutch and establish aerodromes with meteorological facilities for heavy bombers.' The advancing Japanese reached Timor early in 1942. Rofe's party destroyed the same airfield they had so laboriously constructed a short time before; and also arms and ammunition which could not be left to the enemy. The only items retained were limited food supplies, vital radio equipment, meagre medical items and secret documents. Rofe's team was split in two. Half of the members of the RAAF team were sent to a beach to radio to Darwin for a flying boat to take the party off the island. These men were saved by natives who warned them of the presence of Japanese on the beach. With half of his group, Rofe then moved to Army H.Q. in the hills where Brigadier W. C. D. Veale AIF (later Town Clerk of Adelaide) was in command. Unable to assist the army, Rofe and his party took to the jungle-clad hills, aiming to reach the coast—their only possible point of rescue. So began a fantastic 58-day jungle ordeal, a grim cat-and-mouse exercise with the Japanese troops hunting the fugitives. Rofe's story to the T.V. Times went on:

In the jungle they met a native and his son who came to be known as George and Little George. They helped to get food and supplied information about the movements of the Japanese. Another native 'angel' who helped the party when it was dodging the enemy was Trina, a boy who worked in the Kwong Ha Chinese cafe in Koepang before the war. Dr Ghabler, an old Eurasian medico, once hid the party, risking capture and execution by the Japanese. One by one the men died. Food was short; and the never-ending fear that the enemy may be just around the next corner plagued the desperate fugitives. 'It was George who saved us', said Bryan Rofe. The Japanese called upon us to surrender, delivering a note via a village chief on 16 April 1942. The note read:

A RAAF pilot who tried to get help to the stranded personnel was Flight-Lieutenant H. O. Cook, who had done many operational flights from Darwin. Before the war, Cook had been Guinea Airway's chief pilot, and he knew the region well. It was considered by the RAAF too hazardous to land a plane, but Cook was given permission to reconnoitre. During one of his trips, with Pilot-Officer V. Leithhead as co-pilot, Cook's aircraft was attacked by three Zeros. Leithhead acting as gunner downed one, but the others destroyed the port engine of the Australian plane. Then a bullet struck Cook's left arm, and another burst badly wounded Leithhead, the wireless sergeant, and the sergeant air-gunner. Cook did not give up. He made a forced landing in the sea—a most difficult feat in a Hudson aircraft. With the wounded in a rubber dinghy he paddled to the shore, where friendly natives came to his aid. The two sergeants were beyond help. Cook bound Leithhead's wound and then his own arm. Taking what supplies they could they set off to find the lost party. Leithhead told Peter Batten, war correspondent with the Western Australian newspaper, Mirror, that it was a nightmare trip. He wanted to give in, but Cook wouldn't let him and bullied him on. Their flying boots were soon cut to ribbons by the rough tracks. They kept on walking through the night till well after dawn, then they would sink exhausted and sleep until night. At the end of the second day they saw some natives who began making signs and walking ahead towards the beach. Rofe was amazed to see his old friend, H. O. Cook, and a companion staggering towards his RAAF party. Along the Babaoe Road heading for Tjainplong, waves of Japanese planes passed overhead and dropped 500 parachute troops about three miles from the party. Rofe himself attended as best he could to fever-stricken youngsters without quinine or medical supplies. On March 12, he left with a small party for a native village, Naaklioe; when he returned from this daring expedition, he had six blankets, a good supply of rice and some native herbs. Malaria, blackwater fever and tropical ulcers raged amongst the men. One AIF man in the party died from a fearsome combination of fever and snakebite. Supplies, letters and medicines were flown over from Darwin following radioed requests from Rofe's party. But, in two airdrops, countless parcels were lost in the sea.

Then came THE message - an American submarine would call within five days to take them off the island. A signalling system was arranged, and for the following five nights, a fire burned, hidden from searching enemy eyes by tattered shirts. The submarine came, and an officer landed . . . on the very night that an Australian air raid on the island had forced the fugitives under cover. Rofe sent another message and rescue plans were again set out. At midnight that night, a flashing light was seen in the bay. The US submarine Sea Raven had returned to the rescue for the second time. Batten's account in the 'Mirror' of 12 February 1944 mentioned:

The Saturday Evening Post (USA) gives the best available account of the actual rescue from the time the US Navy received a feeble radio cry from the stranded Australians: 'It was decided to attempt to rescue the Australians immediately. Our nearest suitable craft was a submarine, commanded by Lieutenant-Commander Hiram Cassedy. The craft reached the designated point of contact exactly on time. Moving in at night on the surface, she flashed a recognition signal. From the shore came what appeared to be an answering flash. An eighteen-foot wherry with an engine was put overboard and Ensign George Cook, a reserve officer, who was an exceptionally strong swimmer, was selected to lead the party. With him went Joseph McGrievy, a signalman, and Leonard Markeson, quartermaster. Bad luck hit them immediately. The engine refused to give so much as a wheeze. With desperate haste, paddles and oars were fashioned from the tops of ammunition boxes, and finally the three men in the wherry headed towards the beach. On the high and dangerous surf, it was a bad spot to be in. Not only were the Japs all around, but there was a strong current as well as the surf and the useless engine to contend with, and in the water about them they could see sharks, which Cook later described as 'big as torpedoes'. Worst of all, no further signals had come from shore.' 'Cassedy, aboard the submarine, was watching the rescue effort with increasing concern. The situation was not only discouraging, but ominous, and the hour was growing late. Finally, he recalled the men in the wherry, and the boat was hoisted on deck. The submarine stood out to sea to charge her batteries while there was still a protecting curtain of darkness.' 'During the day, the submarine moved under water along the shore on an intensive hunt for a sign of the Australians. Through the periscope, Cassedy and his officers scrutinised the beach, but they found nothing to encourage them. Meanwhile, some of the crew had been improving the makeshift oars and paddles, and Hall had fashioned some crude oarlocks.' 'That night, the submarine surfaced and slipped back to the prearranged meeting place. As they drew near, those on the top-side saw a fire burning on the beach, and through the glasses they could make out figures gathered around. They broke out the wherry from which the engine had been removed, and put it overboard. It bobbed alongside the sub, while recognition signals were flashed towards the shore, but while this was going on, a ship was sighted standing out of the harbour and heading towards them.' 'The submarine was in a precarious position. The wherry was over the side and the deck was covered in men and gear. She was in no condition to make a hurried dive. Fortunately, Cassedy's ship was lying in a small bay. Everything was secured as rapidly as possible, and the sub turned a shooting end towards the oncoming vessel, just in case she discovered them. There was a long wait as the Jap craft loomed closer, and then the enemy passed by to seaward without spotting them, and faded into the darkness down the coast.' 'Quickly the men in the sub rigged up again, and Cook, with the same two petty officers, climbed into the engineless wherry and paddled towards the surf. This time, they dropped anchor outside. Although they could see the fire and distinguish the figures easily, repeated signals still brought no reply.' 'There was a hurried conference in the wherry. Cook announced that he was going to swim in, and contemptuous of the sharks, he slipped into the water. Battling the surf and current, he finally managed to crawl up on the beach, although he had been swept some distance from the fire. Flashlight in one hand, pistol in the other, he started towards it. He turned the dim flashlight on his face so that those about the fire would recognise him as a white man. Confident they were the Aussies he sought, he pushed toward them, shouting loudly, and larding his shouts with good round Navy profanity when he got no answer.' 'To his consternation, as soon as the group around the fire caught sight of him, they leapt to their feet and ran into the bush. Something was definitely wrong. Completely puzzled and more than a little alarmed, Cook took the only course left to him—he plunged into the sea and fought his way back through the surf and sharks to the wherry.' 'Empty-handed, the rescue party returned to the submarine, where their arrival was received with a sigh of relief by her captain. >From the sub, moving lights had been seen from time to time back in the hills. There also had been signals flashed back and forth. It seemed to the Americans more than likely that they came from Japanese searching parties, and perhaps from enemy tanks beating through the bush.' 'Two attempts at locating the Aussies having been unsuccessful, Cassedy decided to report and get further instructions. He pulled clear of the area and moved down toward Australia, in order to be able to transmit his message without disclosing his position to the enemy. Back to him came the information that the Australians had been driven deep into the hills by Jap searching parties, and he was told to return to the rendezvous and try once more to make contact.' 'When the American submarine glided in towards the beach the next time, she got a different reception. Her signals were promptly answered. Yet, as the wherry was put over again, in the minds of all was the question whether the light flashes had come from the Aussies or from Japanese, who had intercepted the messages and managed to decode them. Undeterred, Cook, McGrievy and Markeson paddled towards the surf. Just outside, they dropped their makeshift anchor.' 'On the beach, they could make out a number of shadowy forms. They tried to call to them, and, although neither group could make the other understand what was said through the booming of the surf, the Americans heard enough to realise that at last they had found the Aussie refugees.' 'To his consternation, as soon as the group around the fire caught sight of him, they leapt to their feet and ran into the bush. Something was definitely wrong. Completely puzzled and more than a little alarmed, Cook took the only course left to him—he plunged into the sea and fought his way back through the surf and sharks to the wherry.' 'Empty-handed, the rescue party returned to the submarine, where their arrival was received with a sigh of relief by her captain. >From the sub, moving lights had been seen from time to time back in the hills. There also had been signals flashed back and forth. It seemed to the Americans more than likely that they came from Japanese searching parties, and perhaps from enemy tanks beating through the bush.' 'Two attempts at locating the Aussies having been unsuccessful, Cassedy decided to report and get further instructions. He pulled clear of the area and moved down toward Australia, in order to be able to transmit his message without disclosing his position to the enemy. Back to him came the information that the Australians had been driven deep into the hills by Jap searching parties, and he was told to return to the rendezvous and try once more to make contact.' 'When the American submarine glided in towards the beach the next time, she got a different reception. Her signals were promptly answered. Yet, as the wherry was put over again, in the minds of all was the question whether the light flashes had come from the Aussies or from Japanese, who had intercepted the messages and managed to decode them. Undeterred, Cook, McGrievy and Markeson paddled towards the surf. Just outside, they dropped their makeshift anchor.' 'On the beach, they could make out a number of shadowy forms. They tried to call to them, and, although neither group could make the other understand what was said through the booming of the surf, the Americans heard enough to realise that at last they had found the Aussie refugees.' 'Unable to communicate by shouting, Cook slipped over the side of the wherry, and swam through the surf. He waded out of the water into the midst of the Australians, most of them members of the air force, with a few navy men. Starting with a handful, the party had gradually grown to its present size as other men fleeing the Japs had joined it. Some of the Aussies had been hiding in the bush as long as eighty-nine days, subsisting on what little food they could get from friendly natives. The castaways were in tatters, and all were suffering from extreme hunger. Some had hideous jungle sores on their legs and arms, and only one of them was free from malaria. Three were definitely stretcher cases.' 'In command of the refugee party was an Australian, Flight-Lieutenant Rofe. After Cook had explained to him that it would be impossible to bring the wherry through the surf and get it out again, the leader of the Aussies decided to divide his party in half. Cook had brought a line in from the small boat, and Rofe directed the sixteen men who were in the strongest condition to start out, pulling themselves along as best they could. It was slow and painful work, but at last all sixteen were in the wherry, including the second in command, whom Rofe had sent along while he remained behind.'

The disembarkation of the rescued men landing at Fremantle must have been an unforgettable sight. Most of them were emaciated; the sickest could not speak, could barely breathe. They had to be strapped on specially contrived stretchers and hauled up vertically through the hatchways of Searaven. Most had long, straggling beards. Rofe, pale and thin, was the only Australian man on deck as the submarine nosed towards the jetty.

In hospital, back in Australia, the 33 men began to recover from their ordeal. 'Those Aussies were grand', one of the US officers told Peter Batten. 'They'd been through hell for weeks, they were as weak as babes. But when they learned that the ship was afire, did they get panicky? Not a bit of it! The few who could stand up properly asked if they could do anything to lend a hand; seemed kind of disappointed when we told them everything was O.K.' Cassedy and Cook were each awarded the US Navy Cross; McGrievy and Markeson were promoted. Bryan Rofe and his second-in-command, Flight-Lieutenant Arthur Cole, were awarded the MBE. Corporal Leslie Roy Borgelt of Nhill, Victoria, was awarded the BEM. Rofe was full of praise for Cole and Borgelt, but spoke of all his 'Men of Timor' in glowing terms. Pilot-Officer V. C. Leithhead later lost his life while serving with 31 Squadron RAAF. The Dutch who administered and controlled the Netherlands East Indies before the war were demoralised, as were the other Allies at this stage, by the speed of the Japanese advance, and the ravages of diseases—particularly dysentery—which caused more casualties than the fighting. In the circumstances, Met. personnel found it almost impossible to give forecasts. Nevertheless, a great deal of initiative was displayed in these forward areas. George Mackey found an old AR7 wireless receiver with which his party was able, intermittently, to pick up PLO Bandoeng—the regional forecasting station. Otherwise, the only weather reports available were a few from bomber aircraft on missions. RAAF ESCAPE PARTY - TIMOR APRIL 1942. RAAF ESCAPE Party - Timor, April 1942 A. No. 2 Squadron Personnel.

B. No. 13 Squadron Personnel.

C. Other Personnel. BRIDGE Lieutenant RANVR/ CLEMENTS C. AIF * ( W/T Operator, ex 2/40 Battalion ) attached to No. 2 Squadron. * Flight Lieutenant THOMPSON, Corporal ANDREWS, Aircraftman Class 1 GRAHAM, and Private C. CLEMENTS all died whilst on TIMOR. All other RAAF Personnel and Lieutenant BRIDGE were all successfully evacuated by Searaven.

Five days later, fire broke out in her main power cubicle, immobilizing Searaven completely During April 1942, HMAS Maryborough took the submarine USS Searaven in tow and brought her to Fremantle.

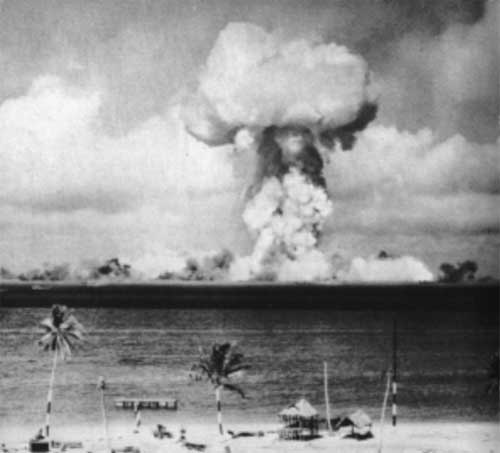

Sea Raven's fourth war patrol was a quiet one and returning from her fifth patrol she claimed 23,400 tons sunk and 6,853 damaged. This tally, however, went unconfirmed. She ended her fifth patrol on 24 November 1942 at Fremantle, Australia, where she underwent refit. On 18 December, she got underway from Fremantle, bound for the Banda Sea, Ceram Sea, and the Palau Islands. In the Banda Sea, she welcomed the New Year by loosing a spread of three torpedoes at the minelayer, Itsuku Shima. Again the sinking claimed by Searaven went unconfirmed. Two weeks later, on 14 January 1943, the submarine pumped four torpedoes into the freighter Siraha Maru and collected her first confirmed victory. On 10 February 1943, she sailed into Pearl Harbor, Hawaii, and, two days later, she set out for overhaul at Mare Island, Calif. She completed overhaul on 7 May and returned to Pearl Harbor on the 25th. On 7 June, Sea Raven departed from Pearl Harbor for her seventh patrol this time in the Mariana Islands area. During this patrol, she reconnoitered Marcus Island, but encountered no enemy shipping. She put into Midway Island on 29 July 1943 for refit. Her eighth war patrol began at Midway on 23 August. She plied the waters off the northeastern coast of Honshu, Japan, but found no enemy ship worth a torpedo. After a month and one-half at sea, the submarine made Pearl Harbor on 6 October. A month later, she stood out for her ninth patrol. She patrolled the Eastern Carolinas and, for a three-day period, operated with a wolfpack of submarines which was used as part of the defensive screen for the Gilbert Islands operation. On 25 November 1943, she got her second confirmed kill, sending the 10,052-ton tanker Toa Maru, to the bottom with four torpedoes. She sailed back into Pearl Harbor on 6 December. Her tenth war patrol, 17 January to 3 March 1944, was occupied by photo reconnaissance of Eniwetok Atoll and lifeguard duty for the air strikes on the Marshalls Marianas, and Truk. She rescued three airmen, but put into Midway on 3 March with no additional sinkings to her credit. On 26 March, she embarked upon her 11th war patrol. Her assigned area was the southern islands of the Nanpo Shoto, the Bonins. She made two attacks during this patrol, claimed two more sinkings, but was officially credited with none. After a complete overhaul at Pearl Harbor Searaven set course for the Kuril Islands area. Twelve enemy vessels were sunk during this patrol. On 21 September 1944, in a night surface attack, the submarine torpedoed and sank an unescorted Japanese freighter Rizan Maru, that had dropped behind her convoy. On the night of 25 September, Searaven engaged two trawlers, four large sampans, and four 50-ton sampans. Searaven passed down the column of eight sampans and two trawlers, 250 yards abeam, engaging from one to three at a time at practically point blank range. Those that did not sink on the first pass were given another dose of the same treatment until all were destroyed. On 1 November, Searaven sailed as part of a coordinated attack group which also included Pampanito (SS-383), Seacat (SS-309), and Pipefish (SS-388)— for her final war patrol. Operating in the South China Sea, east of Hainan Island, the submarine closed out her combat career by sinking one transport of the Hainan Maru class and an oiler of the Omurosan Maru type. With combat ended, Searaven was assigned target and training duties for the remainder of the war. Searaven was one of the target ships in the 1946 atomic bomb test, Operation "Crossroads," at Bikini Atoll. The support fleet of more than 150 ships provided quarters, experimental stations, and workshops for most of the 42,000 men (more than 37,000 of whom were Navy personnel) of Joint Task Force 1 (JTF 1), the organization that conducted the tests. Additional personnel were located on nearby atolls such as Eniwetok and Kwajalein. The islands of the Bikini Atoll were used primarily as recreation and instrumentation sites. Before the first test, all personnel were evacuated from the target fleet and Bikini Atoll. These men were placed on units of the support fleet, which sortied from Bikini Lagoon and took safe positions at least 10 nautical miles (18.5 km) east of the atoll. In the ABLE test, the weapon was dropped from the B-29 Superfortress Dave's Dream (formerly Big Stink of the 509th Composite Group) and burst over the target fleet. In BAKER, the weapon was suspended beneath landing craft LSM-60 anchored in the midst of the target fleet. BAKER was detonated 90 feet (27 m) underwater.

She escaped the tests with only negligible damage. The submarine was decommissioned on 11 December 1946, sunk as a target on 11 September 1948, and struck from the Navy list on 21 October 1948. Searaven earned ten battle stars for World War II service. Note: The text for the history of Searaven, is in the main taken from the Dictionary of American Naval Fighting Ships site at URL: |

||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||