I am researching some family history. I have a report that a Cornelius Johannes Smith perished on board the

Galway Castle when it was torpedoed in 1918. I have

since established that he in fact was killed in France

(Somme) 1/07/1916. As the report of the drowning and the

sinking of the Galway Castle I am speculating that in

fact his father Jan Cornelius may in fact be the Smith

that died with the sinking. I am attempting to obtain a

listing of those that lost their lives to seek out any

Smiths that may have been on board. Can you assist.

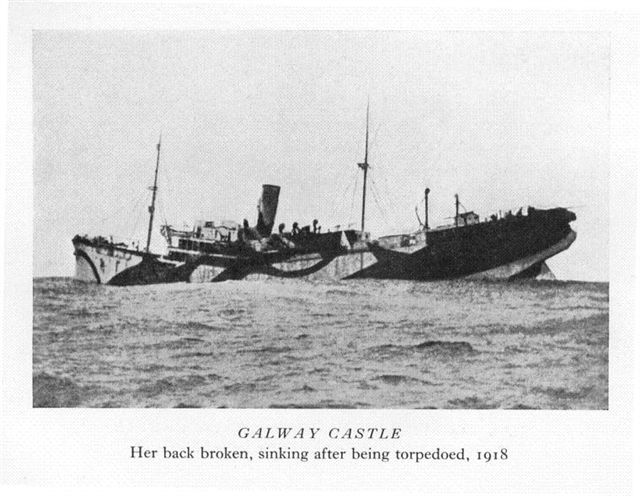

Galway Castle

[For further details and a personal account of the

disaster concerning the Galway Castle see under the

section headed Margaret Catherine Forrester Murray. The

following are extracts from various reports on the attack

against and sinking of the 'Galway Castle]

From newspaper and other reports: (September, 1918)

The 'Galway Castle sailed on 10thSeptember 1918 from

Devonport. Some of the passengers came by train arriving

at about 4 p.m. Monday and went directly on board. The

convoy was made up of 16 steamers, escorted by 2 cruisers

and some destroyers. In ordinary times it was an

Intermediate vessel, acting as a mail steamer but for the

previous few years had been employed in transporting

service men and equipment from Cape Town and South West

African ports during the campaign in South West Africa.

It had been built in Belfast at 8,000 tons, with an

average speed of thirteen and a half knots, being 452 feet

long and 55 feet broad, with twin engines and was launched

on 2nd April 1911.

Its normal intermediate route was to leave London on a

Friday, Southampton the next Saturday and arrive in Cape

Town on Saturday, three weeks later; then up the coast via

East London, Port Elizabeth and to Durban.

The 'Galway Castle left U.K. with 744 passengers aboard

(including 399 invalided South African military men) and

207 crew with a convoy of 27 boats; 16 steamers and being

escorted by 2 cruisers and some destroyers. There was

heavy weather and high seas so progress was slow. ?Thirty

six hours after leaving Plymouth, at 9.30 on September

11th the order was given for the convoy to disperse, the

ships bound for the Mediterranean going in a southerly

direction, while the 'Galway Castle' followed a course

more to the westward, as ordered by the ship that was to

escort her, the armed liner 'Ebro'.? No longer being

kept back by slower vessels, they raised their speed to 11

knots.

An account from one of the survivors: October 1918.

A discharged 'Springbok' soldier in the 1st S. A. I., Pte.

A. H. Middleton, wrote to his parents:

'We all left England in high hopes of being home in dear

old Africa next month but our voyage was all too quickly

brought to an end. We left Plymouth on Tuesday and were

only 330 miles out when the catastrophe occurred. [The sea

was running very high] It was just 7 a.m., and we had

started breakfast, when we were almost thrown prostrate on

our backs by a terrific explosion followed by a thundering

crash. [On the bridge, the Captain and others were

injured, all lights were extinguished, the wireless out of

action and the engines stopped.] We grabbed our life

belts and hurried up on deck, knowing that the worst had

happened. [The torpedo hit the port side but exited,

leaving a hole on the star board side] The passengers

were for the most part only half dressed, [although

Captain Dyer had instructed the passengers to remain

dressed and wear their life jackets at all times] and the

women and children were crying? they were bundled

wholesale into the boats and lowered. ?... everything was

mismanaged. [The evacuation of the ship proved very

difficult as the breaking up of the decks amidship

rendered communications between forward and after parts of

the ship dangerous and it was also impossible for all to

reach their proper lifeboats] Only a few boats were

safely put off to sea, the others were either capsized or

battered against the side of the ship?... [One or more

life boats dropped into the sea upside down?. 18 of 21

were launched but few successfully. Many were killed or

injured by floating wreckage and debris]. I feared the

ship would break in halves and sink. In that case we

should all be taken down by the tremendous suction. So I

darted off to the bow of the ship and heaved over a number

of rafts. [In all, about 40 rafts were launched] Then we

jumped overboard and swam for the rafts. ? I managed to

haul aboard ?... a mother with a three-year-old baby in

her arms. Later on I also picked up three men, which made

a crew of seven. The baby died an hour later of cold and

exposure. [The wind was extremely cold] Poor mother she

lost all three children she had on board??we kept afloat

for over nine hours and were at last picked up by one of

the three destroyers [that responded to the S.O.S.

requesting assistance and sent by wireless by the armed

liner 'Ebro' which departed fearing to be hit as well.]

Many were in need of extra clothing which the sailors on

the destroyer did their best to provide. We lost

everything??. The situation is simply heartrending.?

[In all two submarine destroyers, an American destroyer

and then a cruiser, came to the rescue, bringing survivors

back to England].

From an interview with 'Weekly News' Saturday, September

21st. 1918 with Winifred Murray:

'Regimental Sergeant Major John Murray?? Who is at present

a patient in Stobhill Hospital, Glascow ?. and Mrs.

[Winifred] Murray, who has relatives in Highberg Road,

Hyndland was returning there [to South Africa] with her

three children, Margaret (9 years), Phyllis (6 years), and

Mabel (18 months old).

Mrs. Murray's two youngest children perished in the

disaster, and it was only after she herself had been

landed at an English port that she had the joy of

discovering that Margaret, her remaining child had been

providentially saved.'

'I rushed on deck and put my children into the lifeboat to

which they had been allotted. I found that this boat had

been damaged and we had to go to another boat on the same

side of the liner, but this one could not be lowered, and

we then had to cross to the starboard side of the ship and

actually got into the last boat that left that side of the

vessel.

My children, and especially the infant, suffered in the

crush of trying to get away from the doomed liner, and

just as the boat was lowered a big wave washed us against

the side of the ship. No sooner had the boat rebounded

than another wave carried us against the propeller, which

was even then slowly revolving.

Continuing with great emotion, Mrs Murray stated that when

she looked up she saw her eldest girl's feet disappearing

under the waves and not far away her other girl, Phyllis,

also sank out of view. Mrs Murray frantically clutched

hold of her infant daughter and with her other hand tried

to get hold of Phyllis, but just after that a wave washed

the baby out of her arms?? The great blades of the

propeller as they flashed in the air with water dripping

from them looked like so many murderous knives ready to

cut us in pieces. My poor little child Mabel had her head

cut and we were all thrown into the water'. [She clung to

Phyllis and swam a considerable distance towards a raft]

on which two men were perched. Mrs. Murray hope that her

girl would recover, but the effects of the exposure proved

too much.

When a destroyer hove in sight the survivors on the raft

were in a state of tense anxiety lost in such a rough sea

they might not be observed. The destroyer after cruising

about in search of survivors turned away as if to leave

the scene and it was only by frantically waving a

handkerchief that the attention of those on the warship

was attracted.

To their great relief the vessel turned about and picked

them up - wet, miserable and exhausted, but relieved at

being saved.

[Those on this lifeboat were picked up by the 'Spitfire'

and taken back to Liverpool. The Captain and those

members of the crew who remained on board the 'Galway

Castle' had been safely rescued by this same vessel, which

had approached the sinking ship stern first in order to be

able to transfer everyone. The 'Galway Castle' still held

together for some time and, later, tugs came to tow the

wreck in to shore, but the distance was too great and

three days later she sank]

Messages of Condolence and decrying this terrible tragedy

were sent from:

The Prime Minister of South Africa, General Louis Botha;

the Senior Naval Officer at Simonstown; Rear Admiral

Marcus Rowley Hill, Lord and Lady Buxton and the

Johannesburg Town Council.

As the mayor of Cape Town said, ?The torpedoing of the

'Galway Castle' had brought home to South Africa as, he

thought, no other event during the war had done???. And

the fact that we were fighting for Christian civilisation

against absolute barbarism.?

A Mr Brydon next moved ?That the citizens of Cape Town

desire to place on record the sense of thanksgiving for

those that have been saved, and their gratitude to the

British Navy for its heroic rescue work, and their

admiration and appreciation of the services rendered by

the Mercantile Marine?

Missing Passengers and Crew: (carrying 744 passengers and

207 crew)

Saved Missing Total

First Class 35

18

53

Second Class 101

8

109

Third Class 98

86

184

Invalided Troops (details lacking) 399

Crew 173

34

207

Total 952

* * *

Contribution by Lucy Tarr:

After Dad died in 1964 Mother related a story to me, which

she swore I was never to tell to anyone in the family,

especially on the Murray side. During the 1930's after

Granny & Grandpa May moved to Cape Town, they were staying

down at Clovelly. Granny had gone for a walk and while

sitting looking at the sea, a gentleman engaged her in

conversation. As they both walked along the path about the

same time every day, they got to know each other quite

well.

It transpired that Granny told him the story of Winnie and

the three girls being torpedoed in the Galway Castle,

which sank in the English Channel. This man told her that

he had a friend who had adopted a baby, which had been

picked up after the sinking of the Galway Castle. There

were only two babies of that age on board and Winnie

Murray knew that the other baby had died and thought her

own baby had also perished. This same man told Granny May

that the baby adopted by his friends had been taken to a

port north of Plymouth and the authorities had spent four

months trying to trace the parents but without success.

The man told Granny that she must never try to contact the

child as it would be very upsetting for the family. After

looking at a photo of Winnie Murray he said the girl

looked just like her and he could see a resemblance to

Granny May as well. Apparently she was adopted by a

General Rhys (spelling?) who lived in the Stellenbosch

area and farmed roses. The man told Granny that the

General and his wife had never had children and were very

well off and doted on this child. Granny did go to

Stellenbosch once, I believe, but decided not to try and

make any contact.