Soon the training was over and we were just about ready to go. Christmas 1943 we were still in the Baltic Sea, close to Gdansk. On New Year’s Eve we were in the Bay of Gdansk. Several battle ships and a number of destroyers were also in the bay. That night English warplanes came over to bomb the city of Koenigsberg. Soon the training was over and we were just about ready to go. Christmas 1943 we were still in the Baltic Sea, close to Gdansk. On New Year’s Eve we were in the Bay of Gdansk. Several battle ships and a number of destroyers were also in the bay. That night English warplanes came over to bomb the city of Koenigsberg.

It was the first time I saw a real battle. First a destroyer opened fire on the planes and then the battleship and the cruisers also opened fire. It was like fireworks, only much more spectacular and, of course, deadly for the people who were in it. However, from a distance it was quite exciting and beautiful.

But, I also thought, that if this is war, it’s frightening. I thought of how those pilots and their crew must feel when they see the guns opening up on them. The planes were actually quite high and when the firing started they scattered apart; a few were shot down.

We celebrated New Year’s Eve there, firing off our guns to celebrate. This was at the beginning of 1944. After this we slowly moved back to Kiel, doing some training exercises on the way. In Kiel, we were supposed to be taking on supplies; i.e. food and ammunition.

Suddenly we were ordered back to Hamburg via the Kaiser-Wilhelm-Canal. Our sub was directed to the shipyard called the “Howaldtswerke”. We didn’t know what this was all about but we soon found out. We were told that we were to be outfitted with a snorkel.

The snorkel was something new so nobody knew how it would work. Everything had to be re-arranged in the boat to install it. The snorkel is basically a big pipe with two parts. The air comes into the larger part and the exhaust goes out through the smaller part.

On top of the snorkel is a big floating cap. The exhaust has to come out under water so that only a little steam is visible from the top.

29

The diesel engines suck air through the cap and the fumes are expelled out of the other shaft under the surface. There is not much that is visible on the top.

While the boat was being fitted with the snorkel, we had the duty of standing guard at night in the shed where the boat was being worked on. When I was on duty I arranged with my partner to take turns sleeping. The first two hours my partner could have a nap while I stood guard in the front. Then, it would be my turn to sleep while he stayed by the door. We locked the door from the inside so that we would be warned if anyone came.

But my friend, Heinz, fell asleep while it was his turn to be at the door. He was so sound asleep that when a lieutenant came to the door and wanted to be let in, he forgot to warn me, and opened the door. I heard the officer shouting at my friend and that woke me up.

He shouted:”You were asleep.” He said:”NO!” That’s what I heard, got up quickly, crept back away from the door, and when the officer shouted: “where’s the other guy?” I shouted back from the far corner “Here”. I marched back to where he was and it took me a while. He shone his flashlight at me but he couldn’t really see me until I got closer. Then he accused me of sleeping too, but I denied it vigorously. He kept on insiting that I was asleep and I kept on saying: “No, I wasn’t asleep” This went on for a few minutes. This was the fun we had during that time.

Because of the air raids on Hamburg at the time, many civilians tried to get into the submarine bunkers for shelter. We had to keep guard that they wouldn’t get on the submarines themselves.

Before we left Hamburg to go on patrol, we were granted a final leave with half of the crew going first and then the rest as soon as the first group returned. I went back to my home in Kleefeld and told my mother that we would be going out into battle after this leave. She didn’t react emotionally, she seemed to take it in stride. Four of my siblings were not living at home any more. My sister Emmi was

30

married and living in Bremen. Ruth was working in a hospital in Oldenburg. Hanna was in Warsaw, working at a telephone interchange. My brother Dietrich was at school in Gerlitz. Only my younger sisters, Adda, Erna and Berta were at home. I communicated more with my mother than with my father during this leave. Father was apparently reluctant to risk any conversations about the war. He had been in the infantry during WWI and had been seriously wounded in 1916. He didn’t talk about his war experience.

When I returned to the sub after my leave, we had to practice working with the new snorkel. This practice took place on the Elbe River. The snorkel was still somewhat experimental and we had some interesting times for a while. It took us about a week to learn the skills necessary to make it work.

The snorkel is just about as high as the periscope. So you have to be just at the right depth for the cap to stay on top but not too far out. If it goes under the water, then the diesel engine doesn’t get any air from above and sucks all the air out of the boat. The first time this happened I looked at my partner and his eyes were bugging out. Two diesels running full blast use a lot of air and cause a vacuum inside the boat.

It took us some time to practice getting it right so that the cap of the snorkel was always at exactly the right depth. In the river it was tricky, but on the high seas it would be even trickier. When the air was sucked out of the compartment it was impossible to open the doors in the bulkheads. The vacuum could also do serious damage to our ears, but nobody in our boat had any really bad effects. After a week of practice in the Elbe River we had ironed out all the problems and we were ready to leave Hamburg.

This snorkel helped us of not being detected by radar. In the ocean, there is a lot of debris, such as barrels from ships and so forth. On a radar screen this snorkel would look like another piece of debris on the ocean. If an airplane saw the cap of the snorkel on his radar, it would be too small to be worth investigating or bombing.

31

We left Hamburg to go to Kiel, via the canal, where we were outfitted with food and ammunition and all other supplies we would need. This took about a week. My friend, Heinz, left our crew at this time. He was admitted to the hospital in Kiel with some kind of ailment. I never heard from him again.

I was on guard duty on the pier while the boat was being loaded with food, torpedos and other supplies. When I saw all the boxes of food and other supplies that went down the hatch into the galley, I didn’t think that there would be any room left in the submarine at all. However, when I went aboard later, I saw that everything had been stowed away. Of course, there was less room to move around than before. There were hams and sausages hanging from the pipes above the passages throughout the boat, even in the control room.

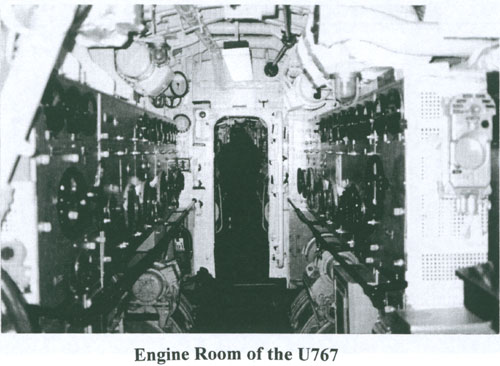

Space in a submarine is very limited; every cubic centimeter has to be utilized as fully as possible in order to do the job that has to be done. Our submarine might have to travel thousands of kilometers between visits to port and the supplies and materials all had to be stowed in this relatively small steel tube with its fifty-three man crew. There is a master list of supplies and every item is numbered and its location in the sub is recorded. When the cook needs certain items, he may come to someone’s space and look behind some of the pipes or instruments to find what he needs.

At last, the torpedos were loaded through the torpedo hatch. It seemed impossible to me that fourteen torpedoes would fit inside the sub, but they did. Two of the torpedos which were not in the tubes, were hanging from the ceiling in the forward compartment where twenty-four of us had our bunks. Four more were stored in the bilge under the deck plates in the forward compartment.

After a week we were ready to go. It was May 1, 1944. We went out with several other subs. There was a little ceremony with speeches and a band playing. The band played “Muss I’ denn, muss I’ denn zum Staedtele hinaus”. This sent a shiver or two down our spine, because we began to realize what this all really meant. This was the real thing. This is what we had been trained for.

32

As we moved out of the harbour, I knew that we really were at war now. I didn’t plan on killing anyone, who was the enemy anyway? And why would I want to kill him?

First we went up to Larwig on the Norwegian coast. When we and two other subs arrived there, we found two subs lying there already. The commander told us to wait here for the invasion. We knew that the invasion was coming, but we suspected it would not be here in Norway. It wouldn’t make sense for the allies to attack us in Norway because of the location of the country, the terrain and the fjords. But we were there to wait, just in case.

We stayed in Larwig for four days and then headed for Christiansund for two days for our final stocking up of food and other supplies for the long patrol ahead. People referred to Christiansund as the end of the world.

On leaving Christiansund, Lieutenant Commander Dankleff gave a little speech about our assignment. We were to go out into the Atlantic Ocean, but first we had to get past the Shetland Islands where British ships were patrolling and looking for U-boats (German submarines). That gave us something to think about. We left the harbour accompanied by two destroyers. However, the commander told us that the destroyers would not escort us very far, since they were needed elsewhere. We were going out on our own.

Sure enough, after half a day, we heard the destroyers’ horns blowing and we answered. They turned off and left, we were on our own. A few hours later we submerged and stayed under water. When we had been down for an hour, we heard a bang and rumbling that scared us. I woundered if we had been hit. But after a moment I said to the corporal “they missed us”. He said “what do you mean by “they missed us”. He chuckled “that wasn’t meant for us, that was a long way off”. We found out later, that the explosion we heard was eighty kilometers away. It came from the Shetland Islands where a destroyer had attacked a submarine. The experienced men on board laughed at us and said “just wait until it is meant for us, then you will hear a real rumbling”.

33

We all hoped, of course, that we would never have to experience that type of “rumbling”. We stayed submerged all the way through the Shetlands, which was a danger spot for us. Our snorkel worked very well, we could stay under water and not be detected. At night we used the diesel engines and the snorkel. During the day, we stayed submerged, using the electric motors and moved steadily out into the Atlantic.

One night we surfaced for a few minutes to dump some garbage. It was weighted down so that it would sink. It was 2:00 A.M., the commander was asleep and the first officer went up to dump the garbage.

I happened to go through the radio shack at the time of our surfacing because I had just finished by shift. I was reading the news that was posted there. While I was there, I got involved in the transferring of messages. The radio operator reported that there was noise up there. He said “sound level five (Lautstaerke 5)” I repeated this message to the first officer in the conning tower. Then the sound level went up to eight.

What the first officer should have done was sound the alarm to dive, because the noise was an approaching plane. But instead of sounding the alarm, he thought he could divert the plane by sending up a balloon covered with metal foil which was supposed to confuse the plane’s radar. We called these balloons “aphrodites”. The first officer had broken one aphrodite by blowing too much air into it and was coming down from the tower to get another one. The radio man was getting upset and said to me “didn’t you tell him the sound level?”

I said “yes”, but by this time it was too late. It was already ratting up above. The second officer sounded the alarm and our commander woke up and got involved in the action. Fortunately the plane had no bombs, but he strafed us and we had two men wounded. One man was shot through the leg and the other one through the hand. The first officer had just gone back up when he was hit by phosphorus and was burned all down his back.

34

As the planed turned for another run, we dived and got out of his way. The commander was furious. He asked me: ”Schmietenknop, the radio operator tells me that you were here and were to transfer the orders. Did you do it?”

“Yes”, I replied “I gave him the message conveyed to me by the radio operator”. The commander then turned on the first officer who had neglected to sound the alarm and instead had come down for another “aphrodite”. He threatened to have him court-martialed. He really chewed him out because he had put fifty-three men in danger by his negligence.

In the meantime, the medical officer worked on the burns of the first officer’s back. When he cried out in pain, the commander said ”shut up, you deserve to hurt more than this.”

Now we had several wounded men on board. Seaman Berg, who had been shot in the leg was unable to do his duty; he had to stay in his bunk all the time. All this, the result of being up on the surface for only about a minute and a half.

We continued on our journey towards Halifax. We were just ready to operate, looking for some ships to sink, when we received the message to head back across the Atlantic. The invasion had started in France, it was D-Day.

We went back to a port on the French coast, where there were bunkers for submarines. We knew that the bunkers had space for us, but when we asked for permission to come in, permission was not granted. They simply did not want us in there. We had unsuccessfully tried for two days to get in to be re-supplied, which would not have taken us long. The reason for refusing us was never explained to us. Our commander was greatly upset, but there was nothing he could do about it. We had to go back out into the English Channel.

When we were close to the invasion fleet, we suddenly received a message to surface. The commander couldn’t believe that this

35

was really from his superiors. So he asked for the message to be repeated and it was the same message. Three times we got the same message to come to the surface. We were there with five other submarines. Two of them surfaced and were immediately bombed by the planes which were constantly flying overhead. We stayed submerged because of our commanders suspicion regarding the origin of this message.

A few days later, I had just come off my shift and had gone to sleep when the alarm sounded. Even though, I was off duty, I still had an assignment in case of an alarm. My assignment was to look after fuses. I was also in charge of flashlights and flashlight batteries.

We had the new torpedos, the “Zaunkoenig” (wren). On our sub, we called them “destroyer death” (Zerstoerertod). These torpedos were not magnetic like the older ones. They aimed themselves by sound. After they had gone four hundred meters from their submarine they homed in on the loudest sound. Our commander had somehow managed to get a full load of these new torpedos. They were all in the tubes, four in the bow and one in the sterm.

The order came to go to battle stations. Our engine was running full speed and that is noisy, so the destroyers knew that we were there. The periscope was out and the commander gave the order:”Tube one to five. Ready”.

When he got the reply “ready” from the torpedo mechanics, he began to aim the boat in the direction of the target. Then the commander said, “Tube one, tube one, tube one, release!” The officer with the commander pressed a button to send off the torpedo, but, at the same time, when the torpedo mechanic heard the command to release he pushed a lever forward which would release the torpedo mechanically in case the elctrical impulse didn’t do it.

Then the commander called for the second, third and fourth torpedos and then the boat turned to send off the fifth one which was in the stern. When a torpedo was released a blast of compressed air send the torpedo off and the boat was suddenly one and a half tons

36

lighter. This weight must be replaced by water immediately so that the boat remains stable. This rapid releasing of the torpedoes meant that the man at the controls of the ballast tanks had to be totally alert. An error could cause the submarine to come shooting out of the water and then we would be as vulnerable as any surface ship.

Then we waited. Did the torpedoes hit the target or not? There was a huge bang and a thunderous rumble. A hit! The whole crew cheered. At that point we didn’t think of the men who were affected. We jutst thought of hitting the ship, which is what we were there to do. It was like scoring a goal. The commander reported that the first torpedo hit amidship and damaged the ship. The second torpedo must have hit the ammunition magazine because it blew the ship into two parts which sank. The commander reported: “Both parts are standing up, both parts are gone”. I learned later, that the ship we sunk was the 1,370 ton British frigate “Mourne”. (Clay Blair, Hitler’s U-Boat War: The Hunted, 1942-1945 (New York: Modern Library, 1998), 589.)

We heard the explosion of the third torpedo but we couldn’t stay around to see what the other torpedoes had done because we had to go down. More destroyers were coming and we had nothing left in the tubes. Being defenseless, we had to get away from there as fast as possible.

Reloading the spare torpedoes into the tubes would take hours of hard work. They had to be winched into position, all the grease had to be cleaned off and then the torpedo had to be pushed into the tube. We had to get away from the destroyers that were still there and those destroyers still on the way. They knew where we were, since they could easily figure out where the torpedoes had come from.

We submerged to get out of the way. The English Channel is about ninety meters deep there and at first we didn’t go all the way down. Our commander decided to fool the destroyers and go down only twenty-five or thirty meters, just below the surface. This worked at first, because the destroyers had their depth charges set for a lot deeper.

37

When we heard the first depth charges that were really meant for us, it really rumbled. We felt like the world was blowing apart. It was like being in a steel barrel with sledge hammers pounding the barrel from all sides.

The lights flickered and there was air hissing here and there. I had to run from one place to another, to put in new fuses and try to correct the problems that showed up. Before I could fix everything, the destroyer came back and set another depth charge.

This time he set the depth charge higher and almost lifted us right out of the water. If he had been just a little higher yet, he would have blown us right out of the water and could have destroyed us by blasting us with his guns. We didn’t have guns to defend ourselves.

We were still fortunate not to be hit and went down to about ninety meters. However, the destroyer didn’t give up. We laid ourselves down on the bottom and shut off everything. Nobody was allowed to move or talk. Every noise could be heard above and we didn’t want them to find us. Everybody had to lie down where he was and breath very slowly. We all had oxygen tanks, but we were told not to use them at first, but only use the air in the sub. We waited and waited.

We thought the destroyer might be gone, but suddenly we heard the ping …. ping ….ping …. of the detroyer’s sonar. It sounded like a little hammer testing the boat from end to end. Then we heard the destroyer’s propellers coming closer again. As soon as he was over us he started testing again.

Then he waited for a while and listened for any sounds from us, and we were listening too. Had he gone away, we would have heard him, but he wasn’t moving. It was very frustrating and nerve-wracking. All we could do was wait, because in the submarine we were totally helpless. There was nothing we could do and the destroyer up above had more time than we had and was in no hurry.

We waited and then we received another depth charge. Everything shook and everything seemed to be coming apart, but our submarine

38

held together. We were still alive and breathing. This routine went on for about four hours. Slowly the destroyer moved away and was finally gone.

We waited for another half hour before we moved. Very slowly we pumped a little air into the tanks to get us off the bottom and very carefully turned on the electric motors. Very slowly we moved out of there, hoping that the destroyer wouldn’t hear us and come after us again.

When we had gone some distance, we came up to periscope level and looked around. The commander said:”a little higher… ah, it looks free”. We didn’t come right up, but travelled under the surface to the French coast with our snorkel giving air to men and engines. The British destroyers didn’t come here, because the German batteries were still camped on the French coast. While moving into this area, where we would be safe, we reloaded the tubes, which took us about a day and a half.

Once again we went back into the channel. We cruised around for several days and then came our own end.

39

Copyright © 2006/2007 Walter Schmietenknop. All rights reserved.

|